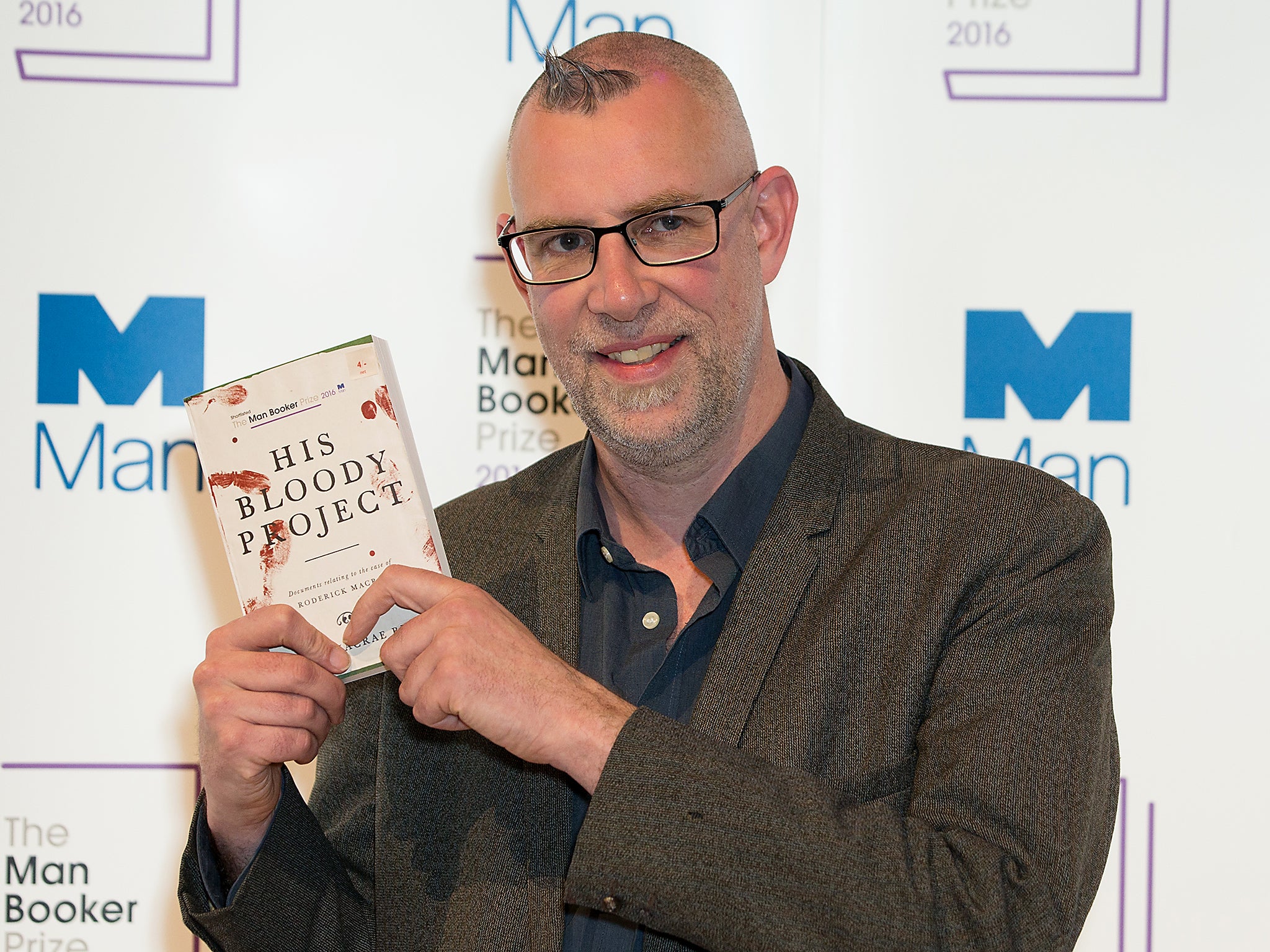

Man Booker Prize nominated book 'His Bloody Project' put Scottish writing back in the spotlight – here is what's next

Scottish literature returned to the spotlight after Graeme Macrae Burnet’s crime novel was nominated for the Man Booker Prize. Timothy C Baker takes a timely look ahead at what else is on offer from Scottish authors in 2017

Thanks to the success of Graeme Macrae Burnet’s His Bloody Project, Scottish literature has returned to prominence lately. The historical novel about a teenage boy who commits a triple murder was a surprise nominee for the Man Booker Prize and an unexpected bestseller. Published by small Glasgow imprint Contraband, it is one of the most successful novels to come out of Scotland in years.

For a country that many like to associate with gritty fare such as Trainspotting and Ian Rankin’s Rebus novels, where does its writing go from here? Besides various other crime writers, the big Scottish noises are mainly established figures such as John Burnside and Ali Smith. Little attention has been paid to emerging writers in their twenties and thirties.

You might be tempted to believe novelist Kirsty Gunn’s widely publicised recent attack on the direction of travel. She accused Scottish literature of having become overly politicised – particularly the way writers are funded by Creative Scotland. She fears the dominance of a nationalist political narrative that awards works that somehow benefit Scottish society or culture rather than artistic merit alone.

While I disagree that there’s a nationalist agenda to blame, I do worry Scottish publishing has become somewhat inward-looking in recent years. With this in mind, here’s what can we expect from the year ahead.

The coming highlights again point to much that is well established – we can expect some high quality. That would include three releases from the always prolific Burnside. There is a collection of poetry, Still Life with Feeding Snake, and his long-awaited new novel, Ashland & Vine (both Jonathan Cape). The novel is about a film student who drinks too much and develops an unlikely friendship with an old woman with a lifetime of stories.

Also from Burnside is a novella, Havergey (Little Toller), which is set on a remote island and explores the idea of Utopia. Combining the same themes as his best work, environmental destruction and community survival, it may again demonstrate his continued relevance to Scottish and British literature – and resistance to easy classification.

Several new works come from internationally established writers who are under-recognised in their country of origin. A good example is Glasgow crime writer Denise Mina, who ought to be seen as one of Scotland’s best living novelists. Her historical crime novel The Long Drop (Harvill Secker) received ecstatic early reader responses. It tells the story of Peter Manuel, a serial killer who lived in 1950s Glasgow, and spent a night with the husband and father of two of his victims before being arrested.

Edinburgh-born writer Shena Mackay also falls into this category. Having spent much of her life in London and now based in Southampton, the writer of acclaimed works like The Orchard Fire (1995) and Heligoland (2003) has never received appropriate recognition as a Scottish writer. Virago will this year publish her memoir and continue to reissue her backlist of 15 novels and collections of short stories. The reissues have begun to cement her reputation as one of the greats, and hopefully the memoir will further showcase her extraordinary talents.

If Mackay and Mina underline the strength of female Scottish writing, Nan Shepherd’s prominence on a new Scottish £5 note is a reminder that the classics were not all written by men either. Shepherd’s hillwalking memoir The Living Mountain (1944) has become popular in recent years thanks to championing by various other writers, yet her three Modernist novels about rural north-east Scotland remain under-read outside of Scottish universities.

This looks set to change thanks to Canongate’s release of The Weatherhouse (1930) this month. With a new introduction by the Orcadian writer Amy Liptrot, whose memoir The Outrun was one of last year’s highlights, The Weatherhouse tells the story of a former soldier’s struggle to adjust to village life after returning from the trenches.

Speaking of vital reissues, Peter Mackay and Iain Macpherson’s The Light Blue Book: 500 Years of Gaelic Love and Transgressive Poetry (Luath) stretches this theme of inclusion to Gaelic verse. It came out just before the turn of the year and challenges popular conceptions with material “that ranges from the suggestive to the erotic to the downright rude”.

On the same theme of minority literatures, the veteran poet Robert Alan Jamieson’s A Hundir Inboos till a Diein Lied: A Poetic Voyage Through the (Linguistic) Margins of Europe (Luath) is set to combine original poems in Shetlandic with translations of work from other marginalised languages, including Hungarian, Icelandic, and Catalan.

But if these various releases are important and interesting in different ways, none address the deficit I mentioned at the beginning. The good news is there are also a couple of promising signs of where Scottish writing goes next.

One is Glasgow’s small publishing house Freight Books. Jim Carruth’s Killochries was one of the most important books of 2015, for example, stretching the boundaries of what Scottish poetry can do in the form of a verse-novel. This year Freight is publishing Carruth’s second full-length collection, Black Cart, which focuses again on his rural upbringing near Glasgow and looks set for a larger audience.

Also on Freight will be The First Blast to Awaken Women Degenerate, the first collection by Rachel McCrum, one of the co-founders of the scene-defining Rally and Broad, a Scottish spoken word/musical cabaret show.

Yet the most discussed upcoming publication of the year is by new publishing venture 404 Ink, which incidentally received funding from Creative Scotland. This month it launched a crowdfunding pitch for its first collection of essays, Nasty Women, and met its target in less than three days.

Nasty Women will showcase a wide array of female voices, many of them new writers, focusing on intolerance and inequality to cover everything from Donald Trump’s America to pregnancy. Like Freight, the arrival of 404 Ink is a sign that when we talk about cutting-edge Scottish publishing, the small publishers are increasingly defining the scene.

Timothy C Baker is senior lecturer in Scottish and contemporary literature, University of Aberdeen. This article was originally published in The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks