Susie Steiner: ‘The less I can see, of the world, the more I can focus’

Losing her sight made author Susie Steiner reflect on the role that blindness has always played in literature

James Joyce was forced to write much of Finnigans Wake in huge letters in crayon, on giant bits of card – using the sliver of sight that still remained to him. “What are you doing with all those cards?” his wife would ask, to which he answered “Trying to create a masterpiece.”

Today, there is voice-activation software, enlarged cursors, and font sizes to help the visually challenged writer such as myself. I am losing my sight to a degenerative disorder called Retinitis Pigmentosa. It is dimming my vision from the outside edges in.

I have good central acuity in one eye, enabling me to read and giving me a small disc of decent daylight sight.

I can even see the fur on a bumble bee, though it would take me an age to locate the bumble bee on the bush. And in low light I am hopeless. I have lost count of the number of dimly lit parties where I’ve pretended to know who I’m talking to.

My sight loss, which has begun to limit me only in the last five years, has accompanied an increase in my creative output as a novelist. The two seem intertwined, as if the less I can see of the world, the more I can focus inwardly.

I no longer commute to an office amid crowds of Londoners – crowds present a terrible visual confusion (I’m a great one for barging and bumping because I can’t see to the side). I stay home. I sit in the attic. I look inside myself and write what I find there. This has brought me great satisfaction and happiness.

It is one of the common misconceptions about blindness that you are either sighted or the world is black. Most of us sit on a spectrum of fading sight, some of it useful, some of it blurry or dim or jagged, universally worsening (I have yet to meet anyone over seven whose sight is improving).

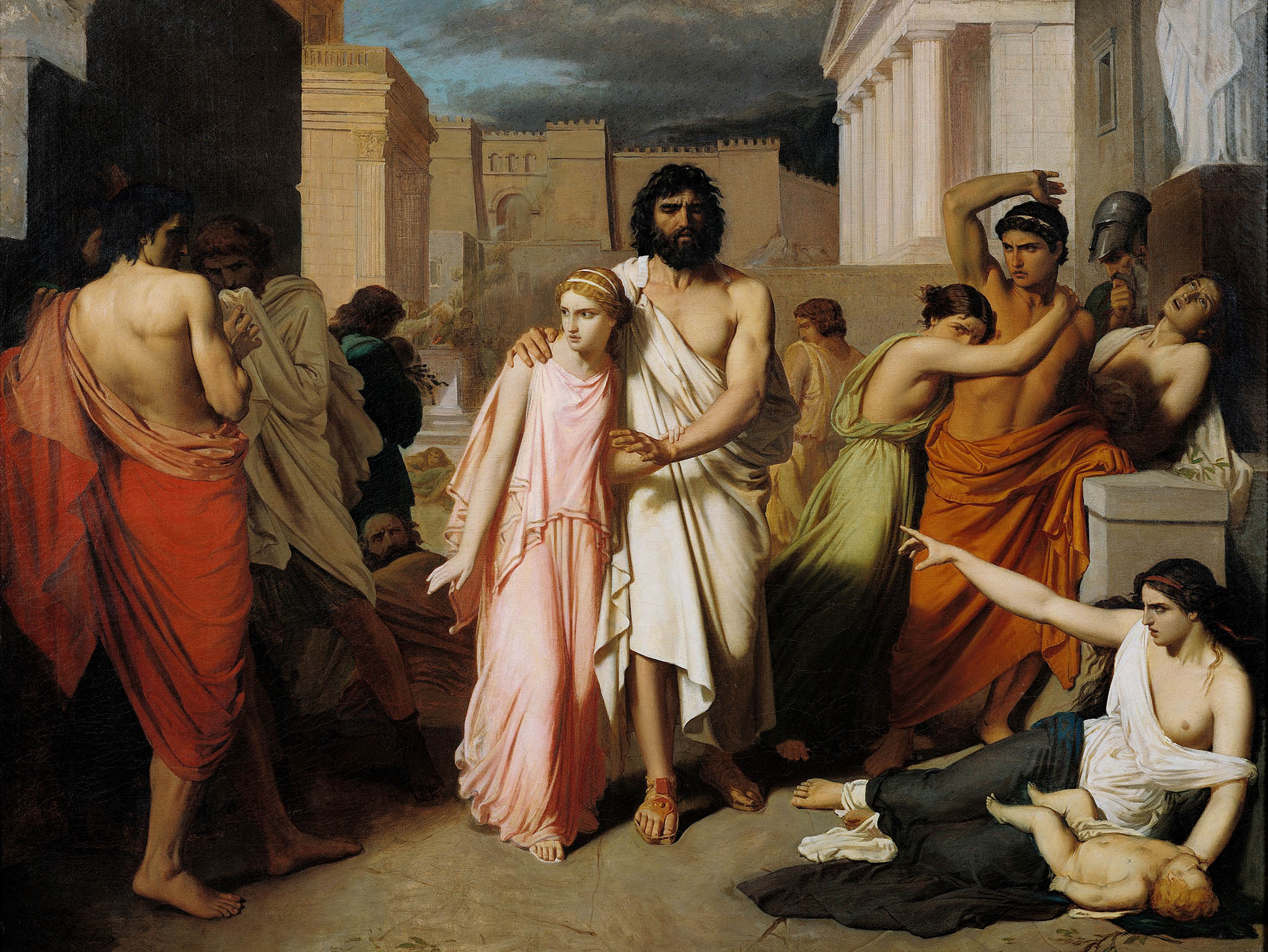

Perhaps this misconception comes, in part, from the huge symbolic role blindness plays in literature: characters who behave blindly and lack vision, characters whose violent blinding follows on from their refusal to face reality, such as in Oedipus Rex.

Good eyesight, our myths and great plays tell us, doesn’t confer insight. “I stumbled when I saw,” says Gloucester, the character who is physically blinded in King Lear, though Lear himself is blind to reality and to the flaws in himself.

It is through madness that he learns to see better, in particular his frailty which he has so stubbornly refused to accept but which is the route to his humanity.

The blind person in society and in culture occupies a dual position – the object of pity for his or her dependence, and lack of vitality (think of Rochester at the end of Jane Eyre). But also sometimes a holder of wisdoms brought about by the focus inwards.

In Greek mythology, the prophet Tiresius is blinded after various transgressions. One poem has him punished after seeing Athena naked – gaze having a connection to shame, in this instance. In another, he gets involved in an argument between Hera and Zeus over whether a man or a woman enjoys sex more.

As Tiresius has been both sexes, he says: “Of ten parts, a man enjoys only one.” Hera blinds him for his impiety; Zeus compensates him with the gift of foresight. He is a “seer” who receives “visions”, which are never wrong.

In reality, as in literature, blindness is an unenviable fate because of dependence. Oedipus, in a terrible act of self-mutilation, gouges out his eyes, making himself forever dependent on his daughter Antigone – an act that cannot be repaired or undone.

The poet John Milton, in his sonnet “When I consider how my light is spent”, mourns his sight loss and ends with the famous line: “They also serve who only stand and wait.”

While this line might be primarily religious in its original meaning, for me Milton is also describing the contingency that comes with disability. You are reliant on another’s help. You cannot dictate – you must wait. This is both frightening and difficult but, I believe, is of service to the writer.

Disability makes you less omnipotent, more fragile and hopefully more understanding of the fragility of others and it creates another kind of empathy – a realisation that one doesn’t know the suffering of others.

Beneath the surface are all manner of grief and heartbreak, not being talked about. The person tooting aggressively at the zebra crossing might just have lost his mother. The colleague being unreasonable in your meeting might be going through a divorce. These undercurrents are the lifeblood of novels and it is empathy which is most in use in the writing of them.

Overwhelmingly, more than a beautiful turn of phrase or plotting pyrotechnics, writing novels requires the ability to imagine yourself into the psychic life of another. It is as if you dig into the dark corners of yourself to find the experiences which overlap with your characters’. And in those dark corners are feelings of fragility, dependence, guilt and loss.

Manon Bradshaw, the main character in my novel Missing, Presumed is not blind, though she does suffer an eye infection in the midst of the high-profile case she’s investigating, and this blurs her vision.

Perhaps I wasn’t able to face the seriousness of permanent sight loss just yet, giving her instead a bout of conjunctivitis that can be cleared with antibiotics. But Manon’s smeared sight coincides with a period of being unable to see the way clear in her police investigation.

“You’ve got to let it emerge,” Manon tells her detective constable, Davy Walker, with rather more conviction than I feel about my own life. “Ride out the confusion, the darkness. You’ve got to allow yourself to be all right with the not knowing.”

In Missing, Presumed, I’m also interested in themes of appearance versus reality – how much is hidden beneath seemingly glossy surfaces: beauty for example, professional success, lives unspoilt by illness or frailty.

I think this stems in part from my defensiveness at being an object of pity. Like the writer Sue Townsend (who was also blind), I cannot abide it. Someone once told me, at great length, how losing his sight would be the absolute worst thing he could imagine. He’s dead now. There really are worse things.

Blindness – or the less tragic-sounding dimming eyesight – is an ordinary fate, a fate which will happen to more and more of us as we age. The Royal National Institute of Blind People predicts that, because of our ageing population, by 2020 the number of people with sight loss will rise to over 2.25 million. By 2050, it’s likely to be nearer four million.

And they say we are all writing a novel, so the rich seam of writing and blindness might grow richer. Certainly, there will always be a place for dependence and frailty in novels: these indignities, so far from the beautiful omnipotence of youth, teach us what it means to be human.

‘Missing, Presumed’ by Susie Steiner is published by Borough Press priced £12.99.

The author will be appearing at Kings Place on 14 March with Detective Sergeant Graham McMillan, who helps her with her books, in an event chaired by Mark Lawson. Book tickets here: http://www.kingsplace.co.uk/whats-on/spoken-word/susie-steiner-missing#.VqnlEPEvx7M.

For more information about Retinitis Pigmentosa, go to rpfightingblindness.org.uk

For a preview of Missing, Presumed by Susie Steiner, follow this link

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments