The young generation: Burroughs and Kerouac - an unpublished collaboration

In 1944, two aspiring writers named William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac were implicated in a murder that scandalised New York. The episode inspired a collaboration, a debut that remained unpublished – until now. John Walsh gives the lowdown on the novel that set them on the road

Fans of the Beat generation have known for years about The Novel That Kicked It All Off, but they've had to wait until the death of a journalist at United Press International for it to be published. The appearance in print of And the Hippos Were Boiled In Their Tanks by William S Burroughs and Jack Kerouac is a literary event, not only because it drew two of the three leading Beat writers into confederacy, but because the book told a story – of male friendship, gay obsession and murder – that came to fascinate a score of American authors.

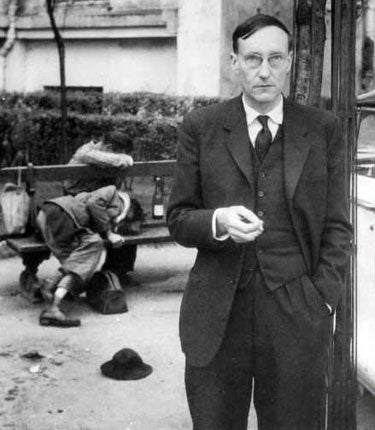

Readers who think Kerouac's 1957 masterpiece On the Road was a young man's book are startled to find that Hippos was written in 1944. The proto-Beat was only 22, a "strange solitary Catholic mystic" from Lowell, Massachusetts. His friend Burroughs, cold, scary and a connoisseur of extreme behaviour, was 30; his years of success with Naked Lunch and Junky came later, in 1959. The third of their troika of strung-out, druggy, sexually ambiguous visionaries was Allen Ginsberg, the gawky, Jewish, voraciously homosexual poet, whose ground-breaking Howl and Other Poems was published in 1956.

A decade before they came to public attention, all were involved in the Carr-Kammerer case. One night in summer 1943, Ginsberg, a Columbia University student, heard music in the dormitory of the Union Theological Seminary. He knocked on the door and asked what it was (Brahms's Trio No 1.) The Brahms fan was Lucien Carr from St Louis, Missouri. They talked and became friends. Carr took Ginsberg to Greenwich Village and introduced him to David Kammerer and to Kammerer's oldest friend, William Burroughs, also from St Louis.

As Christmas approached, momentous meetings occurred. Carr met Edie Parker, a rich Detroit woman and the girlfriend of Jack Kerouac. Kerouac was away at sea but, on his return, Edie introduced him to Carr in her apartment. Carr took Edie to meet Ginsberg, and gave him Kerouac's address. The Beat heroes' first meeting was, prosaically, at breakfast-time; they discussed poetry for hours and later paid a joint formal visit to Burroughs to see what they could learn. It was an ever-expanding literary party.

In the following months, the new friends met in Edie's apartment at 118th Street and Amsterdam Ave. Kerouac came to live with her and her flatmate, Joan Vollman, who later married Burroughs and was shot by him, when a drinking game went wrong, in 1951. For now, though, it was bliss, at the end of a titanic war, to be at the heart of a new generation of writers.

The real-life events behind the book occurred in the early hours of Monday morning, 16 August 1944. Carr and Kammerer were walking beside the Hudson in Riverside Park on New York's Upper West Side. Lucien Carr was 19, slight, blond and good-looking. Kammerer was 33, 6ft tall, athletic, muscular. They'd met in St Louis in 1936, when Carr was 11, and later at George Washington University, when Carr joined nature hikes conducted by Kammerer, the PE instructor. Kammerer was gay and had for years been sexually obsessed with Carr.

Both men were drunk. They quarrelled and rolled on the grass. Kammerer made what the papers called "an indecent proposal", presumably backing it up with action. Carr responded with fury. He stabbed Kammerer twice in the chest with a little Boy Scout knife. Then he put some rocks in the bleeding man's pockets and rolled him into the Hudson.

In disarray, he went to Burroughs, who recommended that he tell his family and consult a lawyer. Instead, he went to see Kerouac, who hung out with him all next day, took him to an art gallery and the new Korda movie The Four Feathers, and watched him dispose of the knife down a sewer and get rid of the dead man's spectacles in the park.

Unable to stand the guilt, Carr went to the police and confessed. Coastguards found Kammerer's body in the river, and Carr was accused of second-degree murder. Kerouac was arrested as a material witness and narrowly missed being charged as an accessory. In an odd twist, when Kerouac's father Leo refused to pay $100 for his son's bail, Kerouac and Edie got married in jail so that her family would pay his bail.

The trial took place on 15 September 1944, and Lucien Carr was sentenced to a maximum of 10 years in jail. No sooner was the sentence announced than several New York scribes began writing their versions of the killing. Ginsberg wrote a draft of The Bloodsong, which recreated Kammerer's last hours, but was discouraged by the assistant dean of Columbia, who decided the university could live without more notoriety. The poet John Hollander wrote about it for the Columbia Spectator. Among others intrigued by the crime-of-passion gay homicide were James Baldwin, and a young copy-boy at the The New Yorker called Truman Capote.

In October 1944, after a period staying with his parents, Burroughs moved into an apartment on Riverside Drive and resumed calling on the apartment shared by Edie, Joan and Kerouac. It was here that the two men began collaborating on their joint novel based on the Kammerer murder.

They wrote alternate chapters, Burroughs as "Will Dennison," a New York bartender, Kerouac as "Mike Ryko," described as "a 19-year-old, red-haired Finn, a sort of merchant seaman dressed in dirty khaki". While many of Burroughs' thematic interests and later obsessions – drugs, violent death, hustlers, gay sex, broken glass – are apparent from an early stage, the young Kerouac held his own against the chilly sage. "There was a clear separation of material as to who wrote what," Burroughs told his biographer, Ted Morgan. "We weren't trying for literal accuracy at all, just some approximation. We had fun doing it. Of course what we wrote was dictated by the actual course of events – that is, Jack knew one thing and I knew another. We fictionalised. The killing was actually done with a knife, it wasn't done with a hatchet at all. I had to disguise the characters, so I made Lucien's character a Turk."

They found an agent, Madeline Brennan, who praised the manuscript and hawked it around some publishers. For a time, things looked promising. On 14 March 1945, Kerouac wrote a letter to his sister Caroline: "For the kind of book it is – a portrait of the 'lost' segment of our generation, hard-boiled, honest and sensationally real – it is good, but we don't know if those kinds of books are much in demand now, although after the war there will no doubt be a veritable rash of 'lost generation' books and ours in that field can't be beat."

You can imagine American publishers in 1945 inspecting the junkie references, the F-words, the gay context ("This Phillip is the kind of boy literary fags write sonnets to, which start out, 'O raven-haired Grecian lad...'") and the hallucinogenic moments – like when two of the characters chew broken glass in Chapter One – and deciding it was too much trouble. None took it on. Burroughs was stoic. "It wasn't sensational enough to make it from that point of view, nor was it well-written or interesting enough to make it from a purely literary point of view. It sort of fell in-between. It was very much in the Existentialist genre, the prevailing mode of the period, but that hadn't hit America yet. It just wasn't a commercially viable property."

It's easy to spot the real Kerouac and Burroughs behind their narrators, and to see Carr and Kammerer behind the figures of Phillip Tourian and Ramsay Allen. The conversation in which Phillip asks Mike when next he's going to sea exactly mirrors what Carr would have said to Kerouac a few weeks before.

The two men stayed friends for life, but the book sometimes came between them. When Carr was released on parole after serving two years, he reinvented himself as Lou Carr, found a job at UPI, the news service, got married, started a family and tried to block any attempts to re-tell the Columbia manslaughter story. He asked for his name to be removed from the dedication (a signal honour) to Ginsberg's Howl.

Kerouac, meanwhile, kept hoping some publisher would bring out Hippos. In the late 1950s and 1960s, he terrified Carr by talking about reviving it. Eventually he told the story under fictional names in his autobiographical novel, Vanity of Duluoz. Then a 1973 biography of Kerouac by Ann Charters brought up the death of Kammerer, and an article in New York magazine, in April 1976, included extracts from Hippos as if they were hard facts. Carr was mortified to have his homicidal past dragged up for his new colleagues to read. Burroughs helped his friend by suing the magazine, and won the right to share control over the book's future.

Burroughs's executor, James Grauerholz, visited Carr after Burroughs died in 1997 and promised he wouldn't allow publication of the novel while Carr was alive. Carr died in 2005, which is why you can read the book at last.

It's not the most sophisticated crime novel, and it doesn't show either writer at his best. But it evokes a time, towards the end of the war, and a place, Manhattan, that's become sour with drunks, whores, sailors, faggots and lost souls, all wondering when the world is going to re-start. It's a fascinating snapshot from a lost era. If you're looking for the link between Hemingway's impotent post-war drifters in The Sun Also Rises, the barflies and Tralalas of Last Exit to Brooklyn and the zonked-out kids of Bret Easton Ellis's Less Than Zero, look no further.

To order a copy of 'And the Hippos Were Boiled In Their Tanks' by Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs for the special price of £18 (free P&P), call Independent Books Direct on 0870 079 8897 or visit www.independentbooksdirect.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks