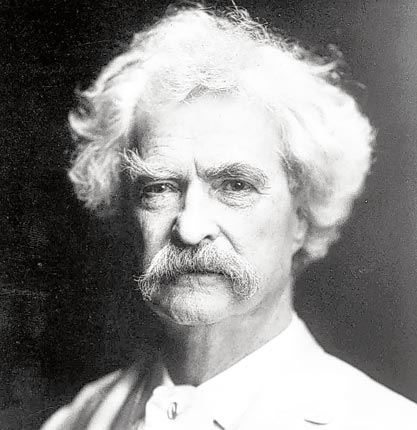

Reports of my memoirs have not been exaggerated

Mark Twain's autobiography has been released in instalments over 100 years. Now the final part has arrived – and it's worth the wait, writes Rupert Cornwell

Autobiographies come in many forms. Some aim to settle scores or, more politely, to "put the historical record straight".

Some (mostly written with the aid of a ghost writer) seek only to cash in on fleeting celebrity. Yet others, generally the best sort, are a wise recollection of things past, written in the Indian summer of life. And then there is the autobiography of Mark Twain.

Twain – or, to give him his real name, Samuel Langhorne Clemens – of course needs no ghostwriter. He is among the greatest and most prolific figures in American literature. But his is not an autobiography in any of the senses above.

Rather it is a colossal, chaotic jumble of writings and towards the end dictations, composed over 40 years from 1870, and consisting of everything from diaries and letters to character sketches, essays, and stream of consciousness reflections taken down by a stenographer. Parts have been published previously, first in the magazine North American Review in 1906 and 1907, and then in book form in 1924, 1940 and 1959.

That was exactly how Clemens wanted it – a slow drip of revelation over the decades. "This book is not a revenge record," he wrote in instructions set out in 1904. "I do not fry the small, the commonplace, the unworthy." Editions, he stipulated, should appear 25 years apart, on the grounds that "many things that must be left out of the first will be proper for the second," and so on until "the fourth – or least the fifth – when the whole autobiography can go, unexpurgated."

Those of a more cynical disposition have seen this device as no more than proof of Clemens' desire to spin out copyright as long as possible. But, be that as it may, the great moment has finally arrived. In a few days, marking the centennial of his death in April 1910, the first part of the complete autobiography, edited by the Mark Twain Project at the University of California, Berkeley, will be published, in what may be America's literary event of the decade.

Volume one alone weighs in at over 700 pages, though, according to Harriet Smith, the chief editor, little more than 5 per cent of the contents will be truly new. That however will change with volumes two and three, when they appear over the next few years. Each will probably run to 600 pages, and "about half will not have been in print before," says Ms Smith.

In the most literal sense, the tomes may not be easy to read; complaints have already surfaced about the tiny print size of volume one. But for connoisseurs of Mark Twain, they are a dream come true, an unfolding discovery of a man who led not one but a thousand lives, as river pilot, printer, silver miner, traveller, businessman, publisher – not to mention writer, reporter, novelist, and, ultimately, living national monument.

Clemens' America is a country of riverboats and of robber barons at the dawn of the industrial age, of Civil War and western expansion, followed by the first flexings of the imperial muscles of a future superpower. As Mark Twain, he is first and foremost the bard of the Mississippi, the creator of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn in a trilogy of magical books inspired and dominated by the immense river flowing past Hannibal, Missouri, where he spent the first 17 years of his life.

But the merit of the autobiography is its revelation of every facet of Samuel Clemens – how modern a figure he is, and how topical his concerns. Take the polemical verve of Christopher Hitchens. Toss in the fun-poking news instincts of the American broadcaster Jon Stewart. Add the traveller's curiosity and gentle wit of a Bill Bryson, plus the raw energy of Ernest Hemingway, and then stir in an entire Oxford dictionary of aphorisms, and you start to get an approximation of a man who spanned virtually every literary genre – and in the process became one of the most quoted (and misquoted) writers to walk the earth.

Are you disgusted with Wall Street and its excesses? So was Clemens. A banker, he once said, "is a fellow who lends you his umbrella when the sun is shining, but wants it back the minute it begins to rain." John Rockefeller might be worth a billion dollars, Twain muses in the autobiography in words that might apply to a 21st-century hedge fund manager, "but he pays taxes on two million and a half".

Or are you fed up with American warmongering in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the self-righteous fashion in which they are presented as for the greater good of humanity? So too would have been Clemens. The autobiography lays bare his opposition to the US forays of his day into Cuba and the Philippines, in language decorously omitted from earlier versions.

In one scorching passage, he describes American soldiers as "our uniformed assassins" guilty of killing "600 helpless and weaponless savages" in the Philippines, in a war that was "a long and happy picnic with nothing to do but sit in comfort and fire the Golden Rule into those people down there ... and pile glory upon glory."

The Mark Twain that angrily skewered high finance and militarism, famously of course had a lighter side – as when he took on the idiosyncracies of German, such as its habit of splitting verbs in two. "The wider the two portions of one of them are spread apart, the better the author of the crime is pleased with his performance," he wrote in his 1880 essay, "The Awful German Language" – a sentiment shared by every student at his first encounter with a floating auf, an, or aus that turns the presumed meaning of the previous 20 words on its head.

Such levity however cannot obscure Clemens' many personal sadnesses, above all the deaths of three of his four children before they reached the age of 25. Sometimes sadness turns to bitterness, not least towards religion. Clemens, as so often, was a jumble of contradictions. He was brought up a Presbyterian. He was a lifelong admirer of Joan of Arc. Yet, he would declare, "Our Christianity ... is a terrible religion. The fleets of the world could swim in spacious comfort in the innocent blood it has spilled."

Above all, though, he was a writer and a storyteller. Undoubtedly, not everything in his autobiography is objectively true, but subjective truth can be equally valid. As he wrote to a friend, "A man's private thoughts can never be a lie; what he thinks, is to him the truth." Samuel Clemens' autobiography uncovers those private thoughts as never before.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies