Bertolt Brecht: A Literary Life by Stephen Parker, book review: Magisterial insight reveals the complexities of a genius

This is good year for those interested in Brecht. A volume of love poems in David Constantine’s translations, a history of the Berliner Ensemble, Brecht’s theatre, by David Barnett, and volumes of his theoretical writings on theatre and performance are forthcoming.

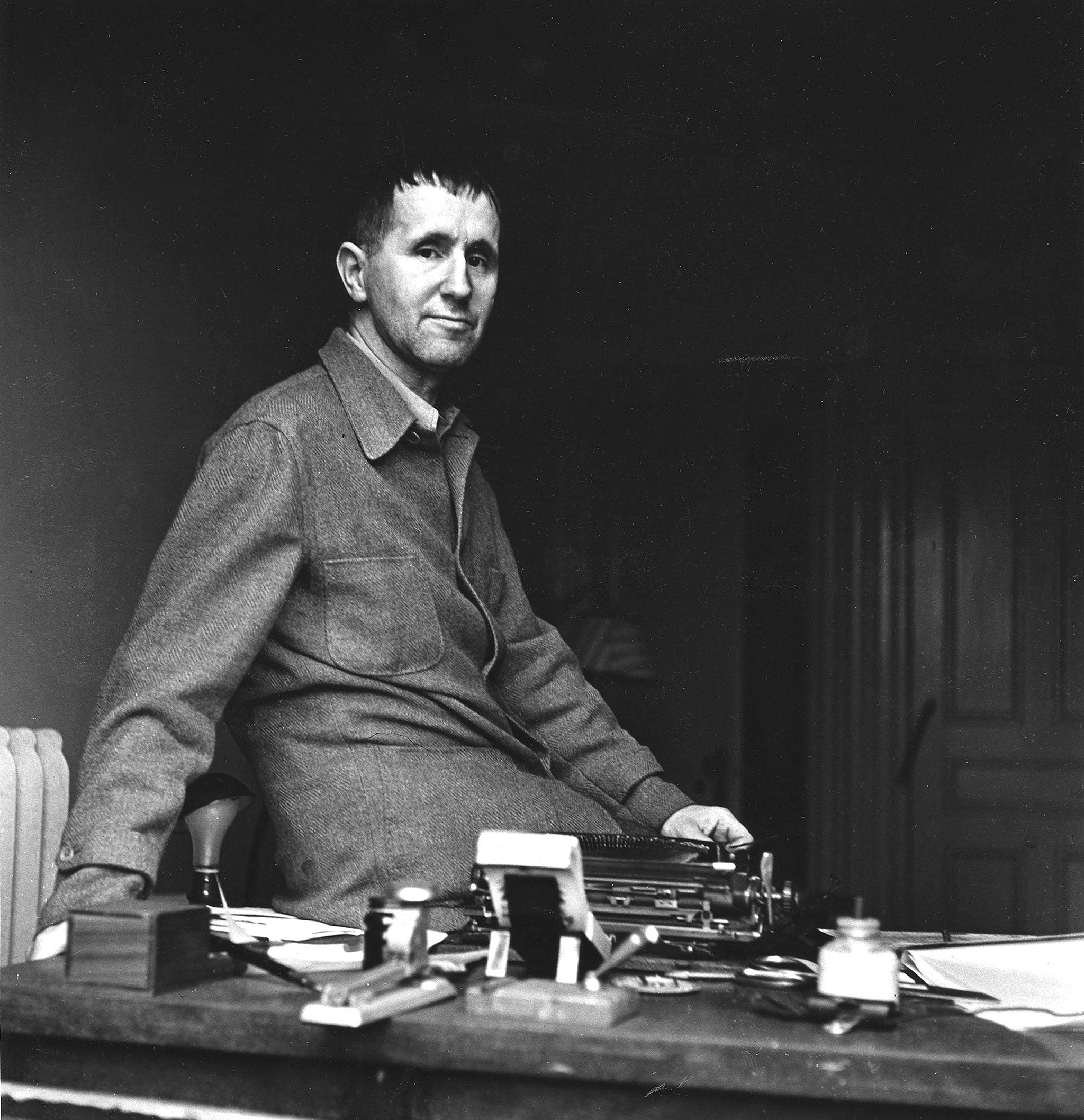

First comes this, a magisterial biography of Brecht the dramatist, the poet, the idiosyncratic, the vitriolic, the tender, the contrarian, the Marxist, the Taoist, the one-time believer in Leninist partisanship, admirer of Napoleon Bonaparte, the reader passionate about Kipling, Verlaine, Rimbaud, Villon, Hölderlin, and Goethe’s quirky Urfaust, drawn visually to Breughel, Bosch, and Chinese ink drawings, fascinated by the figure of Jesus Christ and by the storytellers and swing-boats of Augsburg’s Plärrer and other spring fairgrounds, a friend who inspired devotion but could be cruel, lover par excellence, or, to quote Max Frisch in the late 1940s, simply “the greatest living writer in the German language” with an extraordinary intellectual commitment to change.

Parker handles the vast amount of material, some newly available, with great control and his choice to present it very much through the prism of the artist is compelling. Among the new material, three areas stand out: Brecht’s medical history, biographies on Brecht’s women, and archives illuminating the complications establishing a theatre in Berlin’s post-war Soviet-occupied zone.

Brecht suffered not only from a serious heart problem and near constant renal issues (the excruciating pain of passing kidney stones, the flipside to that organ that brought him such pleasure), but also had a rare neurological condition which demanded equilibrium – not easy to achieve with his character. His burning-the-candle youthful fascination for the hedonistic was countered importantly by his unswerving belief in his genius. He began a lifelong rigorous routine: morning hours of solitary writing, afternoon and evening sessions of collaborative work, conserving his energy for his driving forces of writing and sex. Having briefly studied medicine (scientific and medical vocabulary has its place in his writing), he followed the advances both of conventional and complementary medicine while regarding writing as a healing drug, too.

Essential to a well-functioning Brecht were the extraordinary women in his sphere, often in thrall to him, the most interesting of whom were both intellectually and sensually inspiring companions. Here too, Parker presents the material in impressively restrained fashion, allowing the facts to speak. Again the collaborative aspect was at the fore.

In Elisabeth Hauptmann, for example, Brecht had an exemplary literary secretary (and lover) who translated Kipling’s ballads for him, introduced him to Arthur Whaley’s translations from the Chinese and Japanese, and played a significant role in transforming John Gay’s A Beggar’s Opera into The Threepenny Opera with Kurt Weill, one of two significant commercial successes for Brecht in his lifetime (the other being Hangmen Also Die! with Fritz Lang, conceived on a Hollywood beach.)

Another Berlin New Woman was actress Helene Weigel, Brecht’s second wife and life-companion, depicted with immense warmth, “a figure of brilliance, substance, strength and sexual attraction”: wherever ‘home’ was in the exile years, she created an inviting interior and a circle of like-minded friends, ensuring the intellectually rigorous exchange, prerequisite for them both. There are portraits, too, of the Scandinavian female writers and left-thinkers who afforded the Brecht family (and entourage) safe passage.

The opening of the Berliner Ensemble and other Soviet-zone/GDR archives make clear the complicated dance required for his theatre to become a reality, serene Weigel at the helm. This, the road to publication and to the staging of his plays in his lifetime, the battle of the critics, the support of his bemused father, the sustaining role of the Zurich Schauspielhaus and friendships to Lion Feuchtwanger and set-designer Casper Neher, the Hollywood years where “even the fig trees sometimes look as if they had just told and sold some contemptible lies”, all makes for fascinating reading.

In a time when quiet moments were rare, particularly for one as unusual in character and brilliance as Brecht, those brief hiatuses provide some beautiful breathing-space in Parker’s superb work of scholarship and critical empathy. The chess games with Walter Benjamin beneath that Danish pear tree, for example, or the country home in Buckow in his last years giving rise to some of Brecht’s finest poetry where he allowed himself some moments of unrestricted lyricism. Brecht the firebrand, yes, but open still to the less complicated demands of nature and the melancholy of the émigré:

“Such scents of berries and of birches there!/ Thick-corded winds that softly cradle air/ [. . .]/ The refugee beneath the alders turns/To his laborious job: continued hoping.” (From: Finnish Epigrams)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks