Book review: Pig's Foot, By Carlos Acosta, trans. Frank Wynne

Energetic and impassioned, this Cuban saga reveals more than a dilettante's talent

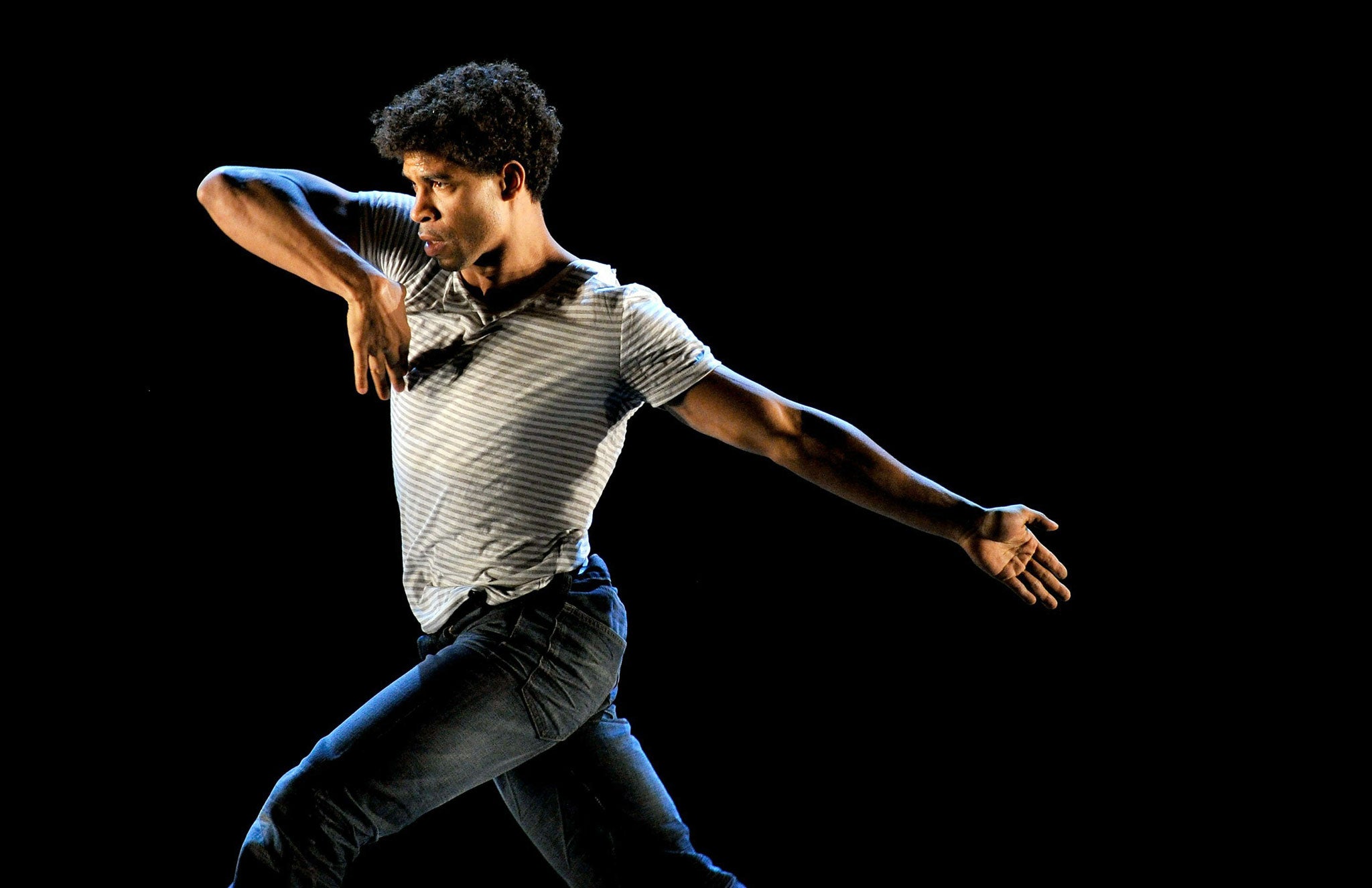

Sometimes creative talent is not confined to a single field. Carlos Acosta is one of the world's finest dancers, a mainstay of the Royal Ballet who can fill auditoriums with ease. Behind his achievements lie the most unpromising of beginnings. Born in a slum in Havana, he break-danced on the streets, away from delinquency and into ballet school. Acosta's memoir, No Way Home, told the story of his remarkable rise, as well as announcing his literary promise.

Get this book at the discounted price of £11.69 from The Independent Bookshop or call 0843 0600 030

Now he is going a step further with a debut novel. It has a memorable opening. Our narrator, Oscar, informs us his recollections "begin on the day I came home from primary school dragging a dead cat by the scruff of the neck". Oscar is telling his story from adulthood, during the "special economic period" in 1995, a time of severe privation after Soviet assistance ended.

Oscar is troubled and confused. More importantly, he is in custody, though what he stands accused of is unclear. He insists on defending himself by recounting his entire family history, back from when his great- grandfather, also called Oscar, was born into slavery.

There follows a sprawling narrative which takes in more than a century of modern Cuba's development. After the horror and degradation of slavery comes the great uprising of 1868, before independence arrives, followed by the machinations of the dictator Batista. Despite this panoramic sweep, much of the novel's action takes place on a small canvas. This is the hamlet of Pata de Puerco, Pig's Foot, whose inhabitants scrape a meagre living from back-breaking agriculture. It is where Oscar's great-grandfather settles, already in possession of the family's dubious heirloom, an amulet consisting of a necklet strung with a shrivelled pig's trotter.

Acosta evokes the sweltering rot of tropical poverty very well and he has a facility with the bizarre and fantastical. Great-grandpa Oscar, for example, comes from a tribe of east African pygmies whose diminutive stature belies their menfolk's enormous penises.

In a preface, Acosta says that novel is set in an imaginary alternative Cuba. Even so, Oscar's erratic flirtations with magical realism raise questions in the reader's mind. Also odd are his lapses into abusive language and his haphazard fast-forwards. Overshadowing it all is the mystery of Oscar's confinement, to be finally resolved along with everything else in an abrupt and unsettling dénouement.

Acosta's translator Frank Wynne captures the energy of Acosta's prose with meticulous and sustained flair. As for Acosta himself, if his style is occasionally uneven, no matter: he drags his story relentlessly onward, in much the same manner as the infant Oscar with his dead moggy. This knockabout epic marks an impressive further stage in Acosta's emergence as a writer.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments