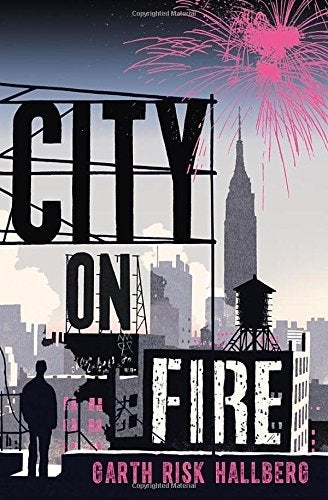

City On Fire, by Garth Risk Hallberg - book review: Big Apple, rotten core

Jonathan Cape - £20

City On Fire begins rather like that other massive New York saga, A Little Life: we have two young men, both artists, both lovers, living in a draughty loft apartment. Mercer is a black man newly escaped from Southern poverty, trying to attain Yankee acceptance by wearing his suit each day to a teaching job at Wenceslas-Mockingbird School for Girls and, by night, sitting blankly at his typewriter from which he hopes the Great American Novel might emerge. His lover, a white man named William, is a heroin addict, painter, former punk singer, and rebellious son of the wealthy Hamilton-Sweeneys.

But whereas A Little Life gradually shed its characters until it focused on the torment of one, City On Fire reaches outwards, encompassing a huge, rattling cast list in an ambitious attempt to capture the squalid, spray-painted world of New York in 1977 where “it was like a bomb had gone off, leaving only outcasts”. Sumptuous penthouse wealth and anarchist Bronx squatters, gentility, divorce, intrigue, adultery and the emerging punk music scene are here, all knotted together by a late-night shooting on a freezing New Year’s Eve in Central Park.

This is the city as it started to curdle, when it was known for homicide, not grandeur, a place where you should not venture out after dark, as evidenced by the finale in which the city is plunged into a blackout and chaos is unleashed on the streets.

Hallberg uses multiple points of view to communicate the vastness of the city and the frenetic jumble of people who survive in it, such as the Jewish boy, Charlie Weisbarger, who’s from tidy Long Island suburbia but wants desperately to be immersed in the gritty punk scene; Regan, the genteel socialite who’s going through a divorce; Mercer, agonising about his lover’s descent into drug addiction; and the lover himself, William, who feels shackled by his partner’s fussy concern. There are also detectives, journalists, groupies and nagging, clutching families. Yet this sprawling cast is the novel’s chief flaw: had it been restricted to the consciousness of a select few the novel would have had more depth, though less staggering scale.

In trying to cover so much ground, running to well over 900 pages, the book feels uneven and indulges in pointless typographical flourishes such as pages rendered in handwriting or as coffee-stained typewritten sheets, but its attempt to capture a whole city and its troubled zeitgeist is gloriously ambitious, even though this ambition often gallops ahead, leaving characterisation behind.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments