WHEN ASKED, SHORTLY after the death of his only client Elvis Presley, what he would do now, "Colonel" Tom Parker was brutally sanguine. "Why, I'll go right on managing him," he replied, doubtless secure in the knowledge that he would be earning more in the future than he had during the star's declining years. As showbiz cynics were quick to acknowledge, Presley's death was a great career move, revitalising a brand that has continued to generate more income since his death than prior to it.

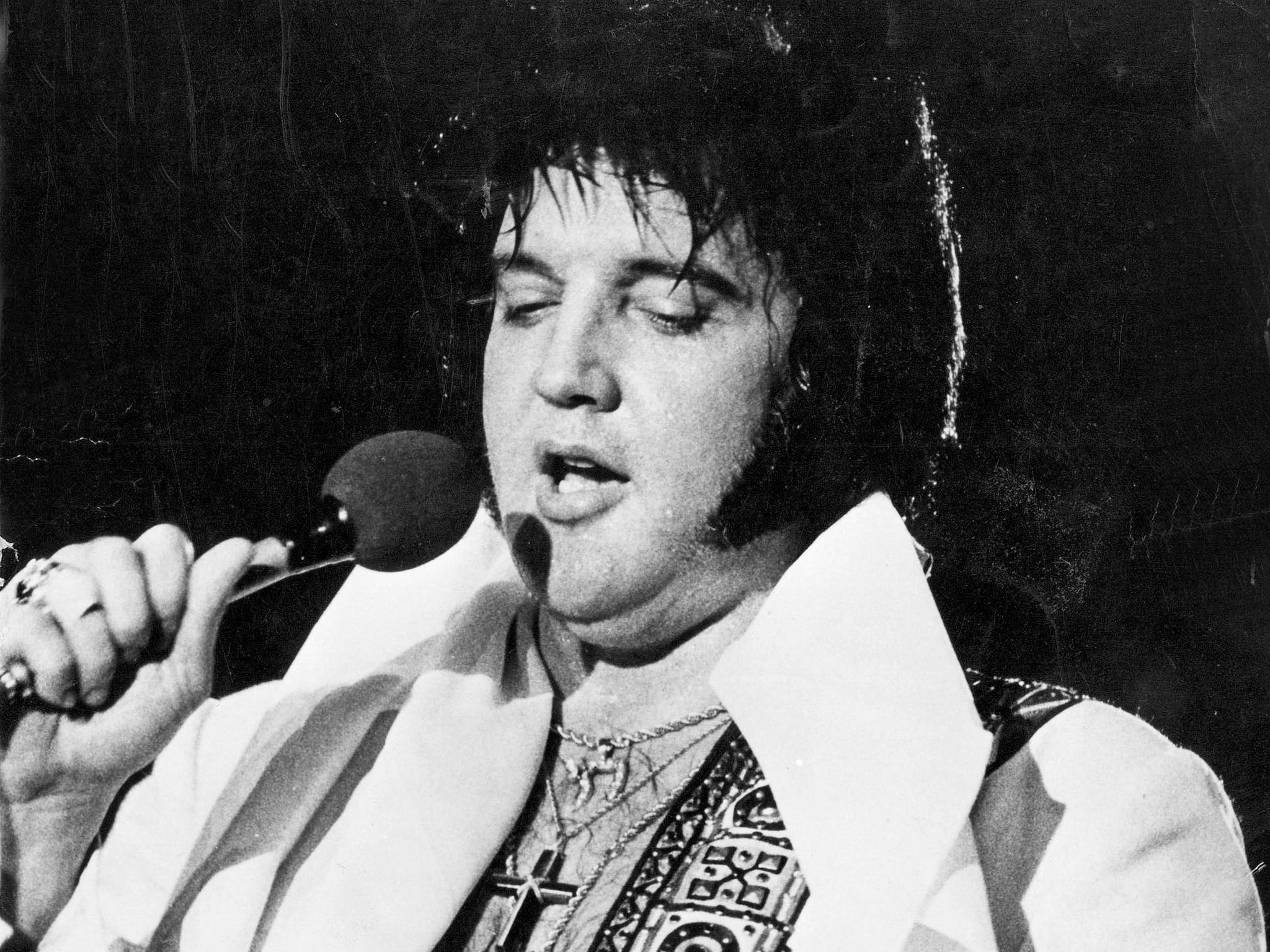

The accepted showbiz wisdom is that stars should live fast, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse, but Elvis failed in all three respects. He may have begun his career as a blazing comet of transformative cultural energy, but as soon as he made that revolutionary, miscegenate breakthrough of marrying black R&B with white hillbilly music, he ceased being creatively curious (in the manner that kept successors like Dylan, Bowie and The Beatles engaged and interesting) and retreated behind the walls of his mansion, his artistic stasis mirrored in his reluctance to travel and his apparent lack of self-reflectivity. As Dylan Jones notes here, upon joining the army Elvis became "so risk-averse that culturally he seemed to implode". Instead of living fast, he sank into a slough of morbid excess, increasingly alienated from the changes rapidly transforming the '60s. And while that fast-living decade took its youthful toll of Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Brian Jones and Janis Joplin, Elvis floated through into his forties, fat and complacent, cocooned within a Praetorian Guard of yes-men keen to indulge his every whim.

He did not leave a good-looking corpse, either. Tumbling from his toilet to the bathroom floor, his face and knees supported his considerable weight until the body was found several hours later. The pooling blood left a facial lividity that the undertaker, Robert Kendall, struggled to conceal cosmetically. Combined with his generally bloated appearance, the effect was distinctly un-Elvis-like to many of the thousands who queued to file past the coffin as the body lay in state at Graceland the next day: instantly, within hours of his passing, the rumours began that Elvis was not actually dead, that only a wax dummy was buried - opening the floodgates for thousands of posthumous Presley "appearances" in decades to come.

Once set in motion, that train of myth and legend about Elvis Presley rolled unstoppably on, sweeping the unsuspecting and disinterested into its wake. When Dylan Jones first learnt of Presley's demise on August 16, 1977, he was a 17-year-old in High Wycombe, anticipating his forthcoming course at Chelsea School Of Art, and musically more intrigued by the burgeoning punk movement than anything as antediluvian as Elvis. But perhaps inevitably for a journalist fascinated by the minutiae of style and fashion, he became more and more interested in the King Of Rock'n'Roll, his appreciation of Elvis as style icon, cultural phenomenon and musical force deepening as the years went on. Elvis Has Left The Building is, however, not just his account of the Presley Legend - what would be the point, when there are biographies more exhaustive and more scurrilous already available, by the likes of Peter Guralnick and Albert Goldman, respectively? - but a detailed examination of the cultural ripples spreading out from the day of his death, viewed through the refracting lens of Jones's own experience.

Accordingly, the book includes copious stuff about punk, tenuously linked to Elvis by the subculture's professed contempt for the fallen idol ("Fuckin' good riddance to bad rubbish," as Johnny Rotten brusquely responded), and by the strands of early rock'n'roll style which, via Malcolm McLaren, informed punk fashion. Punk documentarist Don Letts, it transpires, even sold Sid Vicious a gold lamé jacket, with the brazenly untrue assertion that it had once belonged to Presley. (It had actually belonged to Keith Moon: clearly The Jacket of Doom.) Elvis's actual gold suit, as worn on the cover of 50,000,000 Elvis Fans Can't Be Wrong, became a style icon in its own right when photographed on a clothes hanger by Albert Watson in 1991. Elvis himself apparently disliked the garment, which was too heavy for him to perform in comfortably.

There's a wealth of fascinating background detail about the era, as also about Elvis himself. And Jones's contrasting of Presley's initial appearance as a fully-formed, self-made phenomenon, a "gilded hillbilly", with his formless decrepitude at the point of his death - by which time he had little abiding power or momentum left in the medium he had instinctively transformed - is persuasively done. But there's something woozily disorienting about the way the book swings back and forth between the public and the personal, the macro- and the micro-, which becomes even more discomfiting when Jones begins to weave his own fantasies into the narrative. Initially, he starts by simply pondering the prospect of Presley performing Bowie or Stones songs during the '80s disco boom, or singing a James Bond movie theme, imagining Elvis luxuriating in the melodramatic glamour of a John Barry song. But there's also a bizarre, lengthy fantasy sequence in which he imagines a "darker" Elvis, a lascivious, pornocratic prince far from his humble, courteous public image, stooping to depraved, smutty single-entendre performances for arenas of orgasmic housewives.

It's a weird outburst of fan-fiction that disturbs and rather tarnishes the accumulation of factual detail and informed comment that comprises the book's core. We learn, amongst other things, about Elvis's final "meal" (chocolate-chip cookies and peach ice-cream!); that his hairstyle - "five inches of buttered yak wool", as Jones describes it - was modelled on Tony Curtis's 'do in 1949's City Across The River; and about the extraordinary cocktail of drugs found in his corpse, including Codeine, Morphine, Valium, Valmid, Amytal, Nembutal, Carbrital, Demerol, Elavil, Aventyl, Sinutab, Quaalude, and Placidyl. (It's entirely appropriate that Elvis should have succumbed in a bathroom, as he was by then effectively a walking bathroom-cabinet full of drugs.)

And we get to read other stars' responses to Elvis's coming and his going, and accounts of their encounters with the King. The Beatles were famously bored by the experience: "It was more fun meeting Engelbert Humperdinck,"quipped John Lennon sourly upon leaving; Led Zeppelin's Robert Plant and Presley end up singing "Love Me" to each other; and Alice Cooper - invited up to Elvis's Las Vegas suite alongside Liza Minnelli and porn star Linda Lovelace - is asked to brandish a loaded gun at Presley, who karate-kicks the weapon out of his hand and decks the unfortunate schlock-rocker on the kitchen floor.

"Despite his lifelong pattern of discontent," observes Jones, "there is no profound spiritual autobiography in [Presley's] work." Nor, indeed, was any such potentially catastrophic introspection allowed to invade his Graceland cocoon, the star always surrounded by hangers-on, always distracted with juvenile recreations. It's significant that the most poetic insights into his impact come from the generation of stars he influenced. For Dylan, "hearing Elvis's voice for the first time was like busting out of jail - and I didn't even know I was in jail"; for Bruce Springsteen, he was "the first modern 20th century man, creating fundamental outsider art that would be embraced by a mainstream popular culture"; and David Bowie, who shared Presley's birthday, effectively credited Elvis with creating gender-bending glam-rock: "If his image wasn't bisexual, then I don't know what is," he noted perspicaciously in 1972.

Jones concludes the book with his own annotated selection of favourite Elvis songs in chronological order, from 1954's "That's All Right" to 1977's "Way Down", which with some relief restores music to the foreground, as well as confirming the author's belief that in two brief decades the singer had gone from being "the avatar of US cool to the embodiment of American excess, his life a metaphor for the post-war consumer American dream". Indeed, it's unlikely any other person will ever represent the country's hopes, dreams and failings as fully as Elvis. Part Huckleberry Finn, part Jay Gatsby, part Citizen Kane, part Moby Dick, he was a walking, talking, hip-shaking allegory of a nation. Remember him this way.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments