Inside the Dream Palace: The life and times of New York's Legendary Chelsea Hotel by Sherill Tippins, book review

Everything was permitted at the Chelsea, apart from attachment parenting

Reading this book, transported me back to the blissful few weeks I spent at The Chelsea, in the late 60s. Room 103 was far from salubrious: stained carpets, coughing pipes, but a sanctuary nonetheless. By happy chance, my heroine the communist party member and activist Elizaeth Gurley Flnnn was my close neighbor. In rooms of our own, with no need to interact with the other guests or each other, Flynn and I could focus on the matter in hand. As Flynn had said in her column in the Daily Worker decades before.

‘A hotel. This is a sample for the future, what every woman should have a room to herself and release from domestic tasks.’ In a hotel, ‘the telephone doesn’t ring incessantly, no doorbell, bill collector, laundryman or grocer interrupts my thoughts.’

In these propitious circumstances, I blossomed creatively, completing a book of imagist verse, several confronting immersive ‘happenings’, and edited the second volume of Flynn’s memoirs in my down time.

The level of detail in my false memory is a tribute to Sherill Tippins writing. The reader feels as if she was there, mildly irritated by some of the guests, but in love with the idea of an artistic community which allowed you to be yourself, and participate in a social experiment.

There should be a word to describe nostalgia for something that never happened. An internet search turned up many fellow sufferers, with less glamorous false memories. One older woman feels nostalgic about being a teen in the 90s. ‘I am alone?’, she asks.

The older I get, the more I want to live in a hotel, and my false memory gets more detailed and elaborate with every passing year. Cleaning up after two young children and not being able to hear myself think are two of my main motivations, but I worry that freeing my consciousness would come at a price. Would I die alone, like Margaret Thatcher in The Ritz, unmourned by the family I’d cast off in favour of la vie boheme. A fairly typical Chelsea resident Edgar Lee Masters, freed his mind by sending his two year old child away to live with his wife’s parents while he and Ellen remained in New York.

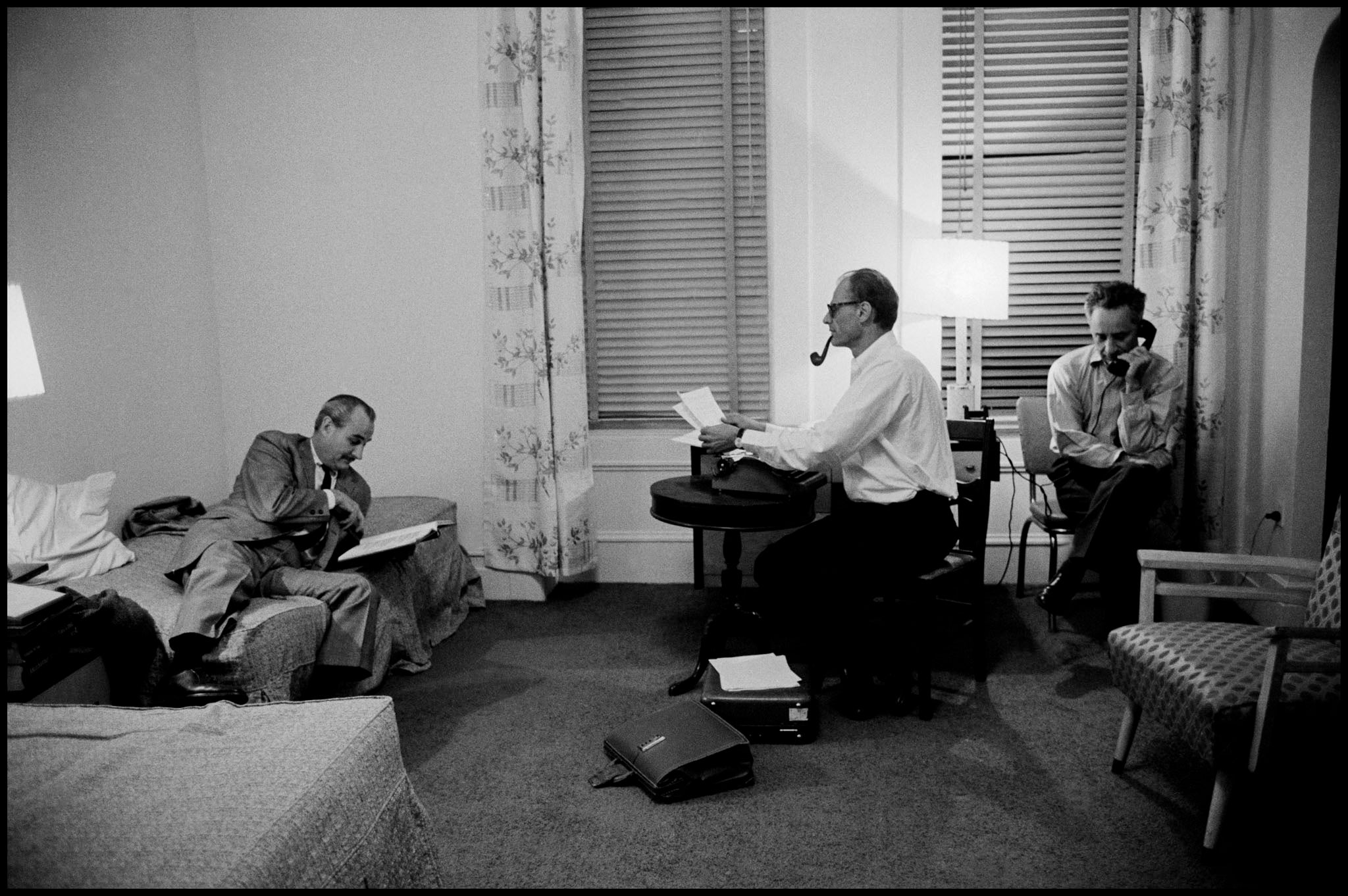

It seems everything was permitted at the Chelsea, apart from attachment parenting. No one knew that resident Arthur Miller had a downs syndrome child. With his son institutionalized, Miller was free to focus all his creative energies on a play that was meant to honestly probe how a moral man like him could cause so much pain – to his 2 ex wives, one of whom was Marilyn Monroe. The son he had abandoned and expunged is denied a third time by being written out of this autobiographical play. The critics disliked After the Fall, complaining that it struck a false note!

This unknown boy was the absent presence in this book, a reminder, as if any were needed that the Chelsea was a haven for narcissists, as well as utopians, and a number of narcissistic utopians. I would have avoided talking to the larger than life characters like the ‘jungle man’ on the top floor who had a menagerie or one of many ‘potbellied guru’s’ if I met them in the lift, though my father has a soft spot for all self-defined eccentrics with no back-story. Like the many Chelsea residents with dark secrets, he believed in self -invention and not looking back. The past caught up with him in middle age (but that’s another story.) He used to drink with Brendan Behans brother in a pub called the Geese in Brighton and would have fallen hard for the writer’s Irish everyman Irish schtick, even though Behan himself was thoroughly sick of it, and drank heavily to escape the conflict between his public and private selves.

There are a lot of conflicted people in this book! Many of the big names fell apart when they were successful, declaring themselves charlatans and frauds before anyone else did, with the notable exception of Bob Dylan. Jackson Pollock said his action paintings were shit: he was making a virtue of necessity; he couldn’t draw, and feared exposure. Tippen tries to distinguish fact from fiction, but happily, her history still reads like a tall tale; as gossipy as any of the Chelsea denizens.

Like America, the Chelsea has had it’s ups and downs. Periodically, it succumbed to the darkness, when the repressed returned and started banging vengefully on the pipes. The toxic atmosphere that led Miller to finally check out, was created, but not owned, by all the artists who pictured utopia as a private island full of hip (or hep) cats, like Richard Branson’s Necker.

Sitting in the lobby in 1967 with a gun in her bag, Valerie Solanas was seeking retribution on behalf of all those who had ever been excluded from an ‘in crowd’ of self proclaimed outsiders. I know just how she felt. In an interview a few years later, explaining her reasons for shooting Andy Warhol, Solanas said ‘I just wanted him to pay attention to me! Talking to him was like talking to a chair.’ I’ve spent many hours being buttonholed by bohemians; their idea of a dialogue is the conversational equivalent of one hand clapping.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies