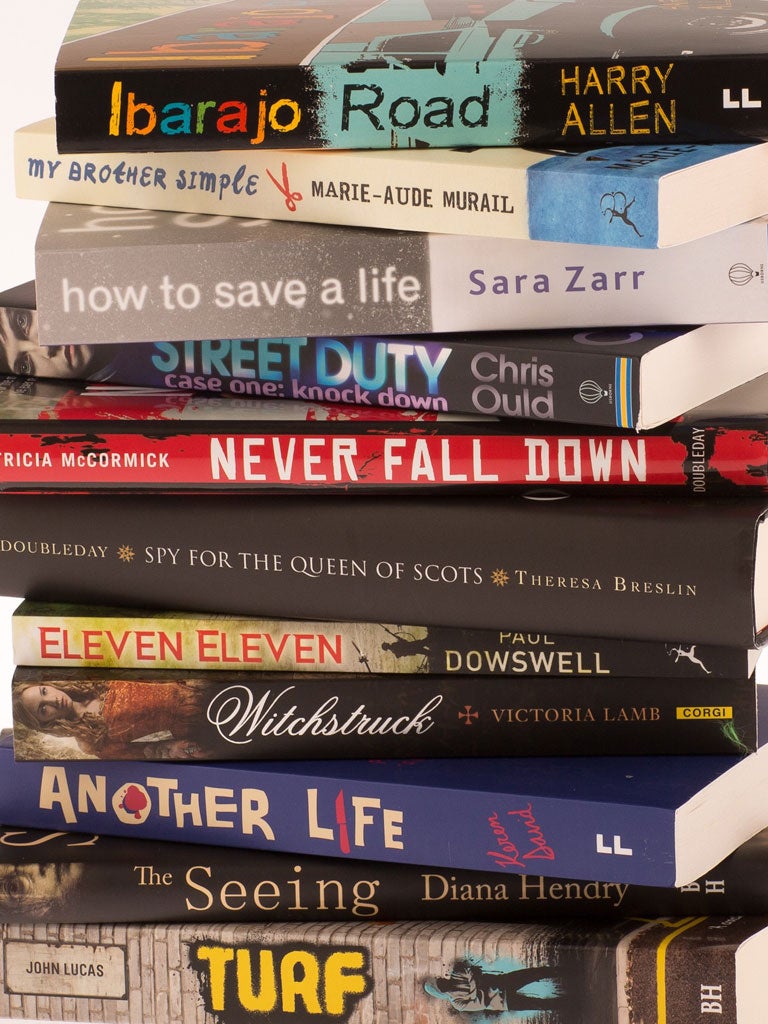

IoS Books of the Year 2012: Teenage fiction - tales of mean streets and magic

Over the next three Sundays we look at the best books of 2012, beginning here with Susan Elkin on teenage fiction

From the doomed life of Mary Stuart to the killing fields of Cambodia and gangland London, there's a fair amount of realistic horror around this Christmas. But to counterbalance it, there are also upbeat stories about siblings looking out for each other, brave teenagers confronting corruption or the divisions of war, as well as a whiff of otherworldliness and a smidgen of witchcraft.

First up are five historical novels. Paul Dowdswell's Eleven Eleven (Bloomsbury, £6.99) is a gutsy, fast-paced tale of three very young First World War fighters – one British, one German and one American – whose paths cross in November 1918. Initially they are suspicious and hostile, but each gradually comes to recognise that his "enemy" is simply another young man. There's rather too much about the technicalities of early 20th-century fighter planes for my taste, but I doubt that it will bother most teenage boy readers, reluctant as I am to stereotype.

Victoria Lamb's Witchstruck (Corgi, £6.99) and Theresa Breslin's Spy for the Queen of Scots (Doubleday, £12.99) are both set 400 years earlier. Meg, a young witch, is a servant to Princess Elizabeth at Woodstock during Mary Tudor's short, brutal, heretic-burning reign. Lamb pulls no punches about the danger both Meg and Elizabeth are in, especially during the horrifying burning of Meg's aunt, who is already sick with cancer. But there's a love interest, and many a teenage girl will fall for the dishy Alejandro de Castillo, of whom we'll hear more because this is the first in a series.

Breslin's protagonist, Jenny, is a royal servant too, this time to Mary Queen of Scots, first in France, then in Scotland and eventually, inevitably, at Fotheringhay Castle. Spy for the Queen of Scots is a strong, old-fashioned humdinger which reminded me how much history I learned and retained from this sort of novel when I was a teenager.

A long way from Tudor England – although there are parallels in the tyranny – is Patricia McCormick's Never Fall Down (Doubleday, £9.99), a harrowing account of the activities of the Khmer Rouge in 1970s Cambodia. Arn Chorn-Pond is the narrator. McCormick, a journalist, has ghosted his story after many interviews with him, and fictionalised it by filling in the gaps. Arn, driven from his home in the midst of one of the worst genocidal atrocities of the 20th century (and tragically, there is no shortage to choose from), became a boy soldier, and managed to survive – eventually to be adopted by an American family – by becoming a musician.

Ibajrajo Road by Harry Allen (Frances Lincoln, £6.99) is set in a thinly disguised 1980s Nigeria where Aids is just beginning to bite. Expelled from his exclusive international school, Charlie, a privileged expatriate, goes to work in a local orphanage to redeem himself. From there, it's quite a journey, as he discovers undreamt of poverty, selfless devotion to helping the poor, and – for himself – friendship and romance. It's a compelling story, teaching you a lot without being off-puttingly didactic.

My Brother Simple by Marie-Aude Murail (Bloomsbury, £6.99), How to Save a Life by Sara Zarr (Usborne, £6.99) and The Seeing by Diana Hendry (Bodley Head, £10.99) are all about family life and relationships. My Brother Simple, which is almost an Of Mice and Men for our times, is a witty, upbeat story of a mentally impaired young Frenchman cared for by his exasperated younger brother, who takes him to Paris rather than allowing him to be shut up in an institution as their father wants. Moving and enjoyable, Zarr's How to Save a Life is about three American women: a widowed mother, her teenage daughter and a young, rejected, abused, pregnant stranger. The mother plans to adopt the pregnant girl's baby, but, as they gradually break down barriers of jealousy and grief, they all three come to realise that perhaps there is another way of creating a family.

Hendry's The Seeing is in a very different mood. Set in a seaside village during the post-war austerity of the 1950s, it introduces us to three children, one of whom, "the wild one", is seriously damaged by everything life has thrown at her, and another of whom may or may not have whatever we mean by "second sight". At one level this thoughtful, rather lyrical story resonates with topical and timeless references; witch-hunts and false accusations, for example. At another, it explores the whole concept of "seeing" and "vision".

And so, lastly, to street violence. Street Duty Knock Down (Usborne, £6.99), the first in a grittily realistic crime series by Chris Ould, is about a rape and murder case solved by two apprentice police trainees. Although Ould has invented the trainee scheme, everything else he writes about police procedures is well researched and page-turningly convincing. Keren David's Another Life (Frances Lincoln, £6.99) is a sequel to When I Was Joe and Almost True, and doesn't make too much sense if you haven't read them. We're in London's gangland again, with two boys, one far more privileged than the other. The tightly written tale involves us with drugs, violence, kidnapping, prison and issues such as failure at school and parental neglect. It's arguably a bit long, but should appeal to readers who enjoyed the first two titles.

Turf by John Lucas (Bodley Head, £9.99) is an unusual and original novel which starts like any other graphic knife-crime story: drug-dealing Jaylon is trapped and controlled by the estate gang he's part of. But then it develops into something else, as the evangelical religion practised by Jaylon's aunt and girlfriend begin to intrude. In the increasingly surreal second half, it's hard to distinguish, if you need to, drug-driven hallucinations from religious awakening, but it's a good read.

How to Save a Life by Sara Zarr

Usborne £6.99

"Now that I'm here, it's different. I'm changing. It's just like I felt my body changing in the first few months of pregnancy, only this time what's changing is something deeper in me. Robin is special. This house is special. I'm more sure all the time. Even Jill, who hates me, has something she doesn't know she has …"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments