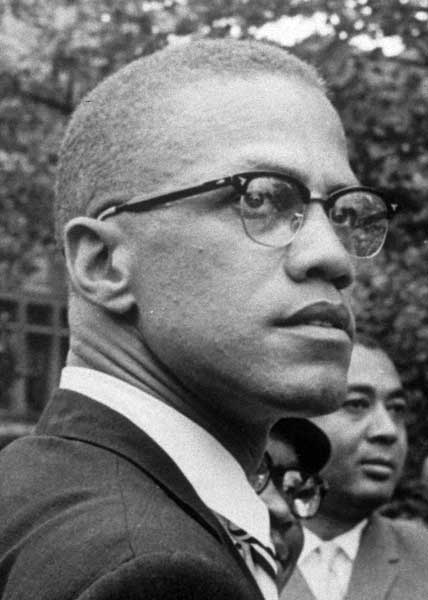

Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, By Manning Marable

The global fame and iconic posthumous stature of the man born as Malcolm Little may seem anomalous, even inexplicable. By most measures, his career was neither very successful, important, nor admirable. Murdered by former devotees at the age of just 39, he left no institutional legacy: the political and religious organistions he founded, always small and fragile, withered away within weeks of his death.

Unlike more quietly effective African-American leaders of his era – a Bayard Rustin or Philip Randolph, let alone a Martin Luther King – he pioneered no legislative or electoral victories, no mass movement, no obvious concrete achievements. Nor was there a significant literary legacy. His inspirational Autobiography was, as Manning Marable shows, far more ghostwriter Alex Haley's book than Malcolm's own.

Most of his public life had been devoted to propagating what he finally scorned as "some of the most fantastic things that you could ever imagine": the Nation of Islam's bizarre mélange of theology, science fiction and racial chauvinism. Although in his last months he was breaking away from those beliefs – and died because of that break - he did so only in ambiguous ways. His ideological evolution was rapid, and was cut brutally short, enabling admirers to project onto him multiple imaginings about where it was going. But it had not (yet?) included clear-cut rejection of ideas he had once propounded: like the inherent evil of white people and especially Jews, the natural inferiority of women, the desirability not just of armed revolution but of political murder, or for that matter that black Gods were circling the Earth in giant spaceships.

Amid all the things Malcolm X was not, there were two great things which he was; albeit one mostly only in retrospect. He was a great talker, and he became a screen onto which millions of people could project their diverse hopes and aspirations. His verbal brilliance was itself of two kinds, as orator and as conversationalist. This made him a crucial transitional figure, between the earlier age of the great face-to-face public meeting and the emerging media world of the soundbite and TV debate.

Malcolm shone at both, in ways which as Marable shrewdly suggests, shared a great deal both with the revered tradition of the improvising jazz musician and the later art of the rapper. If much he said seemed, to sober Civil Rights luminaries as well as to the American establishment, to be mischievously irresponsible, then this placed him within another compelling lineage: that of the black outlaw-trickster. From West African Anancy tales and their North American offspring Brer Rabbit, through folk icons like Stagger Lee to Tupac Shakur, that figure echoes throughout African-American history. As Marable argues, much of Malcolm X's enduring popular appeal came refracted through that imagery, fed always by an enduring sense of black powerlessness.

Whether this tradition will, or indeed should, survive into the Age of Obama is a question at which Marable's biography repeatedly hints, but never fully addresses. Its attitude towards its subject remains deeply, deliberately ambivalent. The central trope is reinvention: how Malcolm Little constantly reworked himself and how commentators and iconographers have repeatedly revised him. Marable gives us all the raw material for a harshly critical appraisal. He shows that the man's early criminality was far less serious and prolific than depicted in the Autobiography - but in some ways more sordid, since it included theft from his friends and family. He skates rather lightly over some of the madder beliefs of the Nation of Islam, but does not conceal either their absurdity or nastiness.

Marable is critical, too, of the "top-down leadership" Malcolm always promoted, and of the sexism from which, despite a few modifying or mollifying remarks, he never broke away. More bluntly, Marable notes how many "violent and unstable characters" were attracted to the Nation of Islam in Malcolm's time, and especially to its enforcer wing the Fruit Of Islam.

If you recruit in prisons, as the NoI so prominently did, you may get many "born again" followers – but you also get something else, really obvious but consistently denied or ignored by 1960s US radicals. Not all prisoners were nascent revolutionaries. Some were, believe it or not, criminals. There is no record of Malcolm ever criticising such tendencies, and eventually he fell victim to them. His own notorious words about chickens coming home to roost were, perhaps, here all too apt. Finally, Marable is explicit about the multiple troubles in his subject's personal relationships, from the tragic strain of mental illness in Malcolm's family to the probable infidelities of both the man himself and his wife Betty.

All this was clearly at times difficult for Marable, for overarching, the more negative evaluations is an intense affirmation. Indeed, his final claim is startlingly laudatory: that "Malcolm embodies a definitive yardstick by which all other Americans who aspire to a mantle of leadership should be measured." Equally, alongside the trickster image of Malcolm is one of stern moral seriousness and rectitude. Spike Lee's 1992 film, which played a key role in reviving the Malcolm X legend, was crippled by those expectations, as many previous writings have also been.

Marable's is very far from the first biography of Malcolm, but is undoubtedly the most penetrating and thoroughly researched. It clearly surpasses the best previous effort, Bruce Perry's 1991 study. Marable produced it at the head of a research team – though this barely diminishes his personal achievement, especially when one learns how gravely ill the author was in the later stages. Tragically, Marable died just days before publication. That makes it hard and sad to say that it is a flawed triumph.

Marable's prose is efficient but blandly anonymous – there is barely a single striking or memorable phrase. His comments on African or Middle Eastern politics are rarely inaccurate, but often disconcertingly vague. And his concluding suggestion that, posthumously, Malcolm X may form a mighty reconciling bridge between American power and global Islam must seem little more than wishful thinking.

Stephen Howe is professor of post-colonial history and culture at Bristol University

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments