Story of a Secret State, By Jan Karski

One night in late August 1939 Jan Kozielewski was dancing at a party in a Warsaw diplomatic legation. A week later he was in uniform and under fire from German forces in southern Poland, an attack that rapidly turned into a rout. The invaders turned the barracks in which his artillery unit had been briefly quartered into a prison camp, which became known by its German name, Auschwitz.

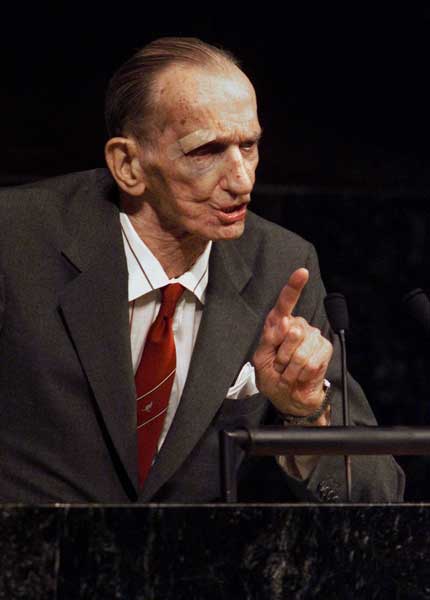

Kozielewski himself became known by his nom de guerre, Karski, as a witness who in the middle of the war told Western leaders and publics about the Nazi extermination campaign against the Jews in Poland. In this "report to the world", written in the US and published in 1944, he described the horrors he had seen in the Warsaw ghetto and at an extermination camp. The book sold more than 400,000 copies and its narrative, simultaneously thrilling and appalling, must surely have transfixed many thousands of readers.

But while Karski bore witness, his reports saved no lives. His readers today will be transfixed too, but they will read his report in the light of hindsight – in the knowledge that the whole truth was so much more terrible even than his testimony.

Karski introduces himself as a somewhat unlikely hero: a young man who wanted to be a demographer rather than a cavalryman or fighter pilot. Yet he discovered a diamond-hard resourcefulness that enabled him to escape from Soviet captivity – he was among the Polish troops who fled the Nazi Blitzkrieg only to be taken prisoner by the Soviet forces that seized eastern Poland – and to carry microfilmed documents across Nazi-controlled Europe, including Germany itself, to the West.

His is not a story of conventional heroism: the cavalryman's charge or the fighter pilot's knightly combat. It is a morally grave resistance in which any attack or escape is likely to cause the deaths of comrades or civilians, because the occupiers follow a doctrine of "collective responsibility". When one underground printing press in Warsaw was raided, German forces not only killed the workers but executed the tenants of neighbouring houses: 83 people died in all. The underground minimised contacts between operatives in order to minimise the names that might be extracted under torture if agents were arrested. By the nature of their role, liaison agents had a wider network of contacts; the life expectancy of the women who carried out these duties was correspondingly short.

Karski himself was a political liaison agent. The underground was much more than an armed resistance organisation, and much more than a secret security state. It attempted to maintain the life of the nation by running clandestine schools, not just because the Nazis had shut down education above primary level, but also to counter what the underground saw as Nazi attempts to corrupt the morals of Polish young people with indecent forms of entertainment.

Most remarkably, it asserted democratic values not just against Nazism but against the colonel-ridden regime that had ruled Poland as the dictatorships rose around its borders. Imitating foreign dictators had failed to save the nation: the proper response to totalitarian oppression was to practice democracy within the resistance. In effect, the politicians who had opposed the colonels used the destruction of the Polish state to stage a democratic counter-coup.

The underground was based on a grand alliance between four parties, ranging from the socialist left – a strong current in Polish politics before the post-war Soviet takeover – to the nationalist right. Such co-operation would have been impossible in peacetime, as anybody who tries to follow Polish politics today will readily appreciate, but in extremis patriotism supervened. Karski's role in this alliance was pivotal. His job was to confer with party representatives and to report their positions, so that consensus agreements could be reached. It was in the course of his political liaison work that he met representatives of Jewish parties, who took him into the Warsaw ghetto.

Karski provides an astonishing insight into the operation of the secret Polish state, but of course his account is a product of the frightful moment in which it was written. It is obliged to maintain security and to emphasise unity; it is unable to reveal the incredulity and inaction with which his reports about the fate of Poland's Jews were received in Western offices of power. His story deserves not just revival but reflection, now that enough time has passed for the agonising wartime histories of central and eastern Europe to be reconstructed.

Deeply welcome as it is, the new edition lacks an introductory essay to provide context and explore the contemporary relevance of the conspiratorial but democratic Polish state. But Karski's electrifying words still speak only too eloquently for themselves.

Marek Kohn's most recent book is 'Turned Out Nice' (Faber)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments