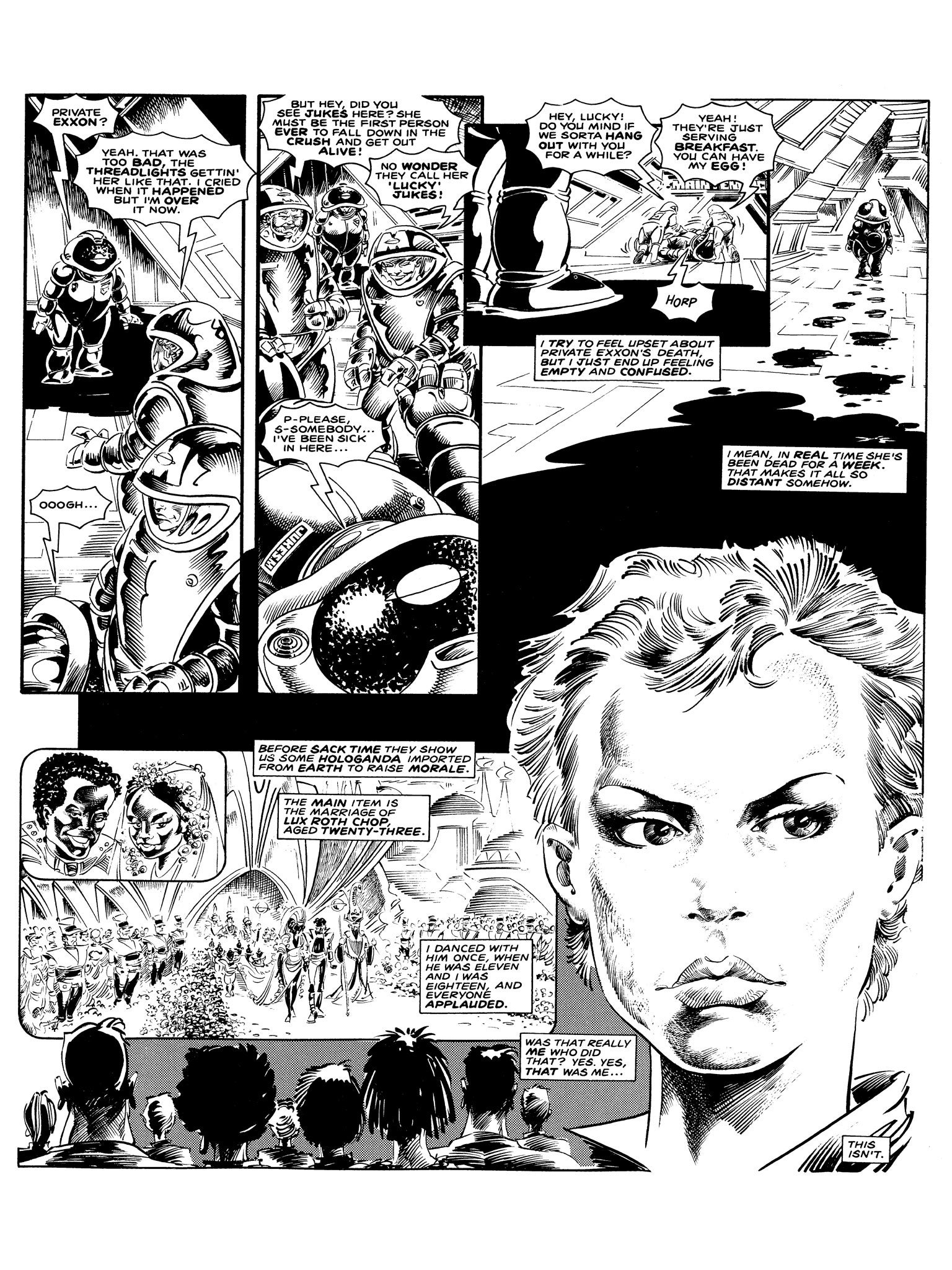

The Ballad of Halo Jones, By Alan Moore and Ian Gibson

An ordinary superwoman who broke the mould

In the world of British comic creators, one name looms large: Alan Moore, creator of Watchmen and commander of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. An iconic figure, who weaves tales of Lovecraftian woe and shuns the superhero genre, Moore has built a dedicated readership around himself yet unexpectedly appeals to a far wider audience than a typical comics creator might hope for. But this is not a recent breakthrough.

In the early Eighties, Moore was determined to bring a woman-led story to the sci-fi anthology comic, 2000AD. The Ballad of Halo Jones was to be the story of an ordinary woman, not a superhero or special snowflake, but a woman who made her own story. 2000AD was already known for its subversion of heroes, but a whole strip starring a woman in a medium apparently dominated by men was a brave move. Moore was striving for a character that represented the everywoman, as opposed to the more common women in comics that often appeared half naked, or as an adornment to a male hero.

The Ballad of Halo Jones broke the mould. Now heralded as a cult classic, reprinted countless times for new generations of readers, the book has finally been bestowed a sophisticated cover designed to appeal to the broader sci-fi audience.

Born on “The Hoop”, a massive housing estate that floats off the east coast of future America, Halo Jones is raised in a society stricken by poverty, mass unemployment and lethal riots. Her hankering for something more from life leads her to the luckiest find of all: a job aboard a space-liner as a stewardess, an employment opportunity awarded for being able to speak the higher Cetacean (dolphin) language. So far, so typical sci-fi escapism for a working class writer in a Thatcherated world.

Yet Moore lingers on Halo’s origin story, her relationships with her friends and the intricate details of the crumbling civilisation she has been trapped within, before moving forwards into the larger galaxy. Driven by despair, increasing numbers of young adults are joining a cult – the Different Drummers – who use implants to quite literally march to their own beat. This latter take on the then new trend of plugging into the world of the Walkman illustrates the satirical edge of Halo’s world, as well as Moore’s well known dislike of the modern technological world.

Almost the entire first act is given over to Halo and her friend Rodice attempting a dangerous shopping trip, timed to avoid the deadly crushes and riots that plague their neighbourhood. It’s a focus that originally left some readers puzzled, but while Halo goes on to adventure across space, the roots of this story are buried in her humble beginnings.

This is a comic about a woman, where women talk to other women about all manner of subjects, where real relationships and agencies exist, and where the hero needn’t resort to sexualised clothing and femme fatale escapades. While the American comics have provided us with many a superwoman, few have managed to subvert the male dominated genre comics quite so effortlessly.

Halo is seemingly cursed with bad luck, as all around her are lost, yet our hero perseveres with the odds stacked against her. It is a story that, despite its Eighties anti-establishment roots, remains remarkably timeless.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies