The Importance of Elsewhere: Philip Larkin's Photographs by Richard Bradford, book review

Philip Larkin’s photographs shift between the transparent and enigmatic

Having previously published a traditional biography of Philip Larkin, First Boredom, Then Fear (2005), Richard Bradford returns to his subject in The Importance of Elsewhere, providing rare animation of the writerly life by means of the replication of 200-odd photographs taken by the poet, including portraits of his family at home in Coventry during his childhood; images of his friends, including the writer Kingsley Amis, at Oxford in the 1940s; snapshots of local life in Wellington, Leicester and then Belfast where he held librarian positions; and a series of pictures charting the building of a new library at Hull University, the work of which Larkin supervised during his time there as university librarian from 1955 until his death in 1985. Arranged in chronological order, but sectioned thematically, the images are accompanied by a welcome amalgamation of biography and analysis in the form of contextual text.

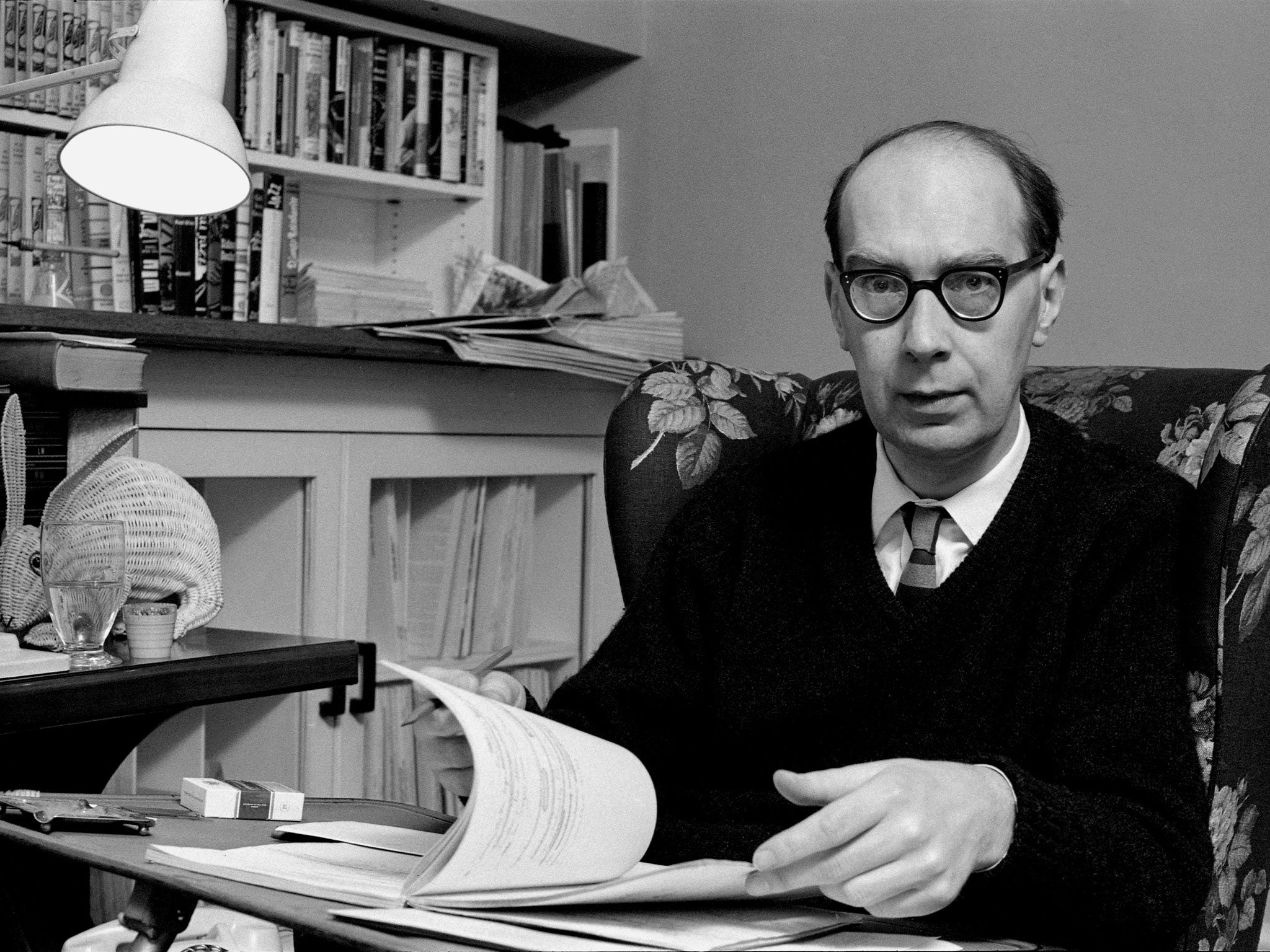

Larkin is both photographer and subject. England's famously provincial and sardonic poet-cum-librarian may not seem the most likely candidate as an early proponent of the selfie, but this book proves otherwise, offering a variety of examples.

He readily availed himself of the tools of his day – in a letter written to a friend in 1947 he confesses to having spent £7 (more than a week of his net salary at the time) on a camera in "an act of madness". As Mark Haworth-Booth, formerly curator of photography at the V&A, puts it in his foreword, the poet was in possession of "all the accoutrements of the serious amateur: a Rolleiflex Automat twin-lens reflex camera, mounted on a tripod, with a cable release to make relatively long exposures in poor light." Larkin also cropped his images in order to achieve the composition he wanted, the end result a notably different effect to the original, as illustrated here by some before-and-after examples. And, when it came to his selfies, Bradford describes him as using carefully positioned mirrors to achieve "an expression that perfectly suited his desired shift between transparency and something more enigmatic."

Many of the photos demonstrate an odd juxtaposition between considered configuration and an attempt to capture something raw and real, not least the rather imposing and more than a little unsettling self-portrait that adorns the front cover. Larkin crouches – head held high, but mostly hidden body stooped – over his Rolleiflex. His bow-tie and woolly jumper are a nod to the amateur at work, but the unflinching eyes behind his steel-framed glasses holding the viewer's gaze somehow suggest a different story. The longer I look at it, in fact, the more I'm reminded of screenshots from Michael Powell's Peeping Tom.

Was I surprised then not to discover pages of pornography? Given what we've learnt about Larkin since his death, a figure previously regarded as melancholy and misanthropic has tumbled over in the much less inviting realms of misogyny and racism. The discovery of a secret cache of scandalous prints would have been not altogether shocking.

Instead, however, I'm greeted by a host of holiday snaps ("Ed. Bay, shortly after I fell in nettles," reads the handwritten note on the back of one, referring to Eddrachillis Bay in Scotland), and a beautiful collection of images of rural churches (inspired, despite the photographer's lack of faith, by his fascination with medieval religious architecture).

There are some slightly more risque offerings. Portraits of lovers with just the hint of eroticism – often, Bradford points out, women posed in strangely similar positions and settings as their predecessors, though whether this implies a particular fetish or simply a lack of imagination he doesn't speculate; but thinking about it, perhaps it's not that odd for a man who spurned monogamy and commitment to be starting very precisely over again with each partner.

Also worth a mention is a strange image of his mother, Eva, beneath a museum wall of old rifles, "carefully posed", suggests Bradford, having explained that Larkin didn't have the most straightforward of relationships with either of his parents. For the man who composed the famous lines, "They fuck you up, your mum and dad", this doesn't come as a huge shock. It was an area of the poet's life Bradford skilfully illuminated in First Boredom, Then Fear, and a subject he continues to feed here, describing the household in which Larkin grew up as an "eerie blend of bohemianism and lunacy".

In many ways Larkin seems to be a case in point for that old adage that one should never meet one's heroes: dig beneath the surface and all you find is dirt. If needs must, however, Larkin's trusty Rolleiflex seems by far the most telling medium through which to come face-to-face with the man behind the lens.

Frances Lincoln, £25. Order at £20 inc. p&p from the Independent Bookshop

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies