The Rest on the Flight: Selected Poems, By Peter Porter

The late Peter Porter, as selector Sean O'Brien puts in his preface to this generous choice from 19 volumes and half-a-century of wonderfully singular poetry, broke all the rules that Kingsley Amis once set about forbidden topics for verse. Shamelessly, he wrote not just about "other poems and paintings and foreign cities and museums", but operas and sonatas, philosophers and cathedrals, generals and gods; even, in "The Apprentice's Sorceror", of the CERN particle accelerator primed in its "Swiss Hole" to recreate "how the universe began". With shocking Australian cheek, he sauntered into every minefield for a timidly populist age and came back with treasure to be enjoyed by any reader with a nose for new discoveries, an eye for bold connections and an ear for the ever-flexible music of his verse. Yet it's typical that his landmark poem about a cultural icon should address itself not to a painter or thinker but a stuffed animal: the racehorse Phar Lap in the Melbourne Museum, the beastly idol who followed a Classical recipe for greatness: "To live in strength, to excel and die too soon".

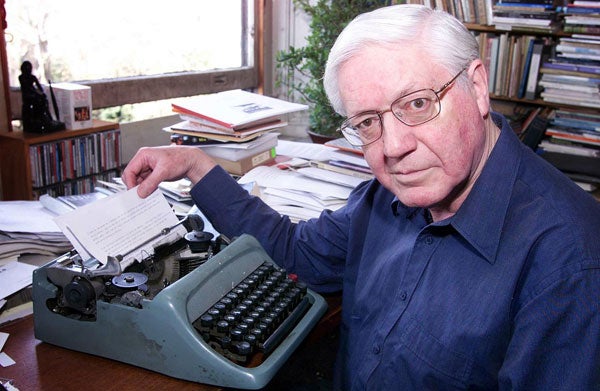

Porter (1929-2010) also died too soon, for all the smooth long haul of his achievement. This collection reveals not merely a fiercely consistent poet: the hard-grafting migrant forefathers in the first poem who engineered bush churches in a week and had "no life but the marking-time of work" are ancestors of the leave-taking artists in "Opus 77", the next-to-last, who at their exit "hope to find the courage to/ Confront the mad god of the universe/ and honour one more time those rational/ Constructions we have loved". It also gives a portrait of one who grew ever more like himself – more distilled, direct, urgent – as he aged. Late volumes such as Max is Missing and Better than God rank with the best he ever did.

As a young outsider already marked by bereavement, adrift with eagle, sometimes envious eyes in clapped-out Europe as it pursued its Sixties dream of youth and pleasure, he seems to have known from the off where his true vocation lay. The curious spectre at the feast, the candid friend who whispers the discomfiting truth (or, sometimes, the Aussie scoffer who takes us down a peg or two), he rattles the bones of time and loss in the middle of the museum, the concert – or the orgy.

His poetry knows that (as "Nevertheless" has it) "its task is still to point incredulously/ at death, a child who won't be silenced,/ among the shattered images to hear/ what the salt hay whispers to tide's change/ dull in the dark, to climb to bed/ with all the dross of time inside its head". Porter does not so much wear his deep learning lightly as fit it so snugly to his verse that it feels more like skin (the "salt hay" line comes from Ezra Pound). One day, perhaps, an Annotated Porter will show us the whole wardrobe.

In a lesser writer, the marriage of mortality and mutability with such long-jump erudition - Martial to Mozart to Meredith – would lead to indigestion. "You've eaten Europe," as a late poem has William James say to constipated brother Henry, "now digest it well". Porter, the non-graduate ex-advertising man from Brisbane who travelled in "the realms of gold" via the Paddington and Westminster public libraries, wolfed it all down with a democrat's sauce. He protests in the lecture-room; he giggles in the hall. "Ex Libris Senator Pococurante" shrinks the Western literary canon into satirical thumbnails: so in Paradise Lost, now "Eden's End", "Our classicist author makes Adam a market/ gardener while Eve assembles Lifestyle hints/ on Post-Coital Guilt and PMT".

If, like the ageing connoisseur in Italy voiced in "Berenson Spots a Lotto", Porter too may rank as "the last admiring ghost/ Of Europe's genius", then that wonder comes shaded by a latecomer's sorrow, an Antipodean irony and a humane sensitivity to the modern kinship of civilisation and barbarism. The Blake-like "Both Ends Against the Middle" matches the Spitfire's Rolls-Royce Merlin engine and Donatello's sculpture, "Humanism's judge and jury/ The Alpha and Omega of delight".

Besides, what Rilke or Wittgenstein or Donizetti might have meant or now mean makes up only one course of the banquet here. The great sequence of elegies from The Cost of Seriousness, prompted by his first wife's death, anchors both the book and the career. Their stricken tenderness of grief finds perfect forms for a bleak apprehension that "What we do on earth is its own parade/ and cannot be redeemed in death". These are, quite simply, classic poems of mourning.

Glimpses of his tough Australian forebears, always saltily strong, grow in authority until, in "Hermetically Sealed or What the Shutter Saw", a family photo from 1911 (surely another item for the Amis banned list) captures a little parable of the coming century, enriched with all the anguish, humour and regret that comes from knowing the fates of these faces. One, the angelic baby Edna, would in future know "how best/ To fend off pain with laughter, work and kindliness".

From a defiantly secular poet "forced" – a final poem, written in 2010, says – "to seek the stars on earth" – we won't expect any salvation more abstract than that. "What works you did will be yourself when you/ Have left the present" – but, with Porter, than implies no dull marble monuments but frisky, witty and companionable stories in verse about the people, ideas and creations that fill a life, a world.

A fleet-metred virtuoso of stanza and shape, Porter shone at every form he tried. Shelve him with Auden and Browning, his artfully versatile kin. The former copywriter would even have approved this book's superior jacket blurb, which calls his work "one of the literary miracles of our time". So it is. Reader, don't wait for the "competitive product" to come along, as the painfully funny "Consumer's Report" on the brand called "Life" has it. Buy this one while you can. It's new, but will not be improved.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments