The story of Gandhi’s early experiences of segregation, sparked by South Africa’s apartheid

"Gandhi before India", By Ramachandra Guha (Allen Lane, £30) »

In Natal on South Africa’s eastern coast, during the apartheid years, school tours of local historical sites would often take in the provincial capital of Pietermaritzburg with its fine Victorian public buildings.

A standard site was the railway station, yet here the buildings were not the main item of interest. Rather, the teachers indicated that we pupils should take a special look at the “famous” platform. Why famous? We asked, but the teachers had no answer. Our touring parties concluded it must be something about the wideness of the platform that made it special. Once there was some vague talk about a foreign holy man who passed by here, but who he was we were not told.

It was only much later that I discovered it was on this platform that Mohandas Gandhi, then a young, unknown Indian lawyer in transit to Pretoria, was made to feel the full weight of the colony’s “colour prejudice”. As the possessor of a first-class railway ticket, he had had to be escorted off his train by a constable when he refused to remove to third class. And from that point, history tells us, he resolved to fight the injustices of racial segregation to which his fellow Indians in South Africa were subject. His South African years would “sow the seeds of his fight for national self-respect”.

It is almost unbelievable to think that there was a time not so long ago when a state’s obfuscation of history to maintain white supremacy went to the extent of erasing the imprint on colonial Pietermaritzburg of one of the outstanding leaders of the 20th century. Significant changes since then have, in respect of Gandhi, steadily brought into sharper focus the 21 formative years he spent in South Africa. It is this fascinating tale of Gandhi’s shaping of two nationalist struggles, India’s and South Africa’s, that Ramachandra Guha’s accomplished biography – the first volume of two – tells. It gives the back-story of Gandhi’s emergence as a satyagraha warrior.

Thanks to the biographical work of historians like Judith Brown, Martin Prozesky and Stanley Wolpert, the shaping influence of South Africa on Gandhi’s vision for India has been acknowledged for some time. Gandhi before India extends and consolidates this case for the “outer-national” formation of the national leader. Guha’s title, which riffs on an earlier work, India after Gandhi, succinctly captures this apparently contradictory core idea.

Gandhi before India is supremely a historian’s biography, down to its evident relish for new documentary evidence. Gandhi’s “sometimes forgotten years” up to 1914 are recounted in a respectful way with little psychological speculation. The different phases in the making of the Mahatma are traced in strict chronological fashion, like symbolic stages in the life of the Hindu god Ram (the analogy is explicitly made).

It is ultimately not the myth of Gandhi, but his creation of a myth of India while in South Africa, that this book seeks to explain, and in this it triumphs. Gandhi before India is as exhaustively researched a biography of the African Gandhi as we will have for some time.

Guha’s work has previously been distinguished for the breadth of its resources, and this book is no exception. He has turned up “dozens of letters” by both Gandhi and his associates not in the official Collected Works, as well as Gandhi’s first campaigning articles (on behalf the Vegetarian Society in London), and a previously untapped wealth of newspaper resources. The result is a biography with a remarkable ear for the resonances of Gandhi’s work and time – for the fan-mail and hate-mail; for overheard disagreements with family and colleagues; for his exchanges with political acquaintances, including his enemies.

Guha’s unemphatic style, though it gives a well-contextualised portrait of his subject, does have a drawback, especially when it comes to an individual as complicated as Gandhi. As Guha avoids dwelling on obscurities in the record, some of the complexities of Gandhi’s remarkable story are elided with the result that he often remains an enigma, as both an activist and a leader.

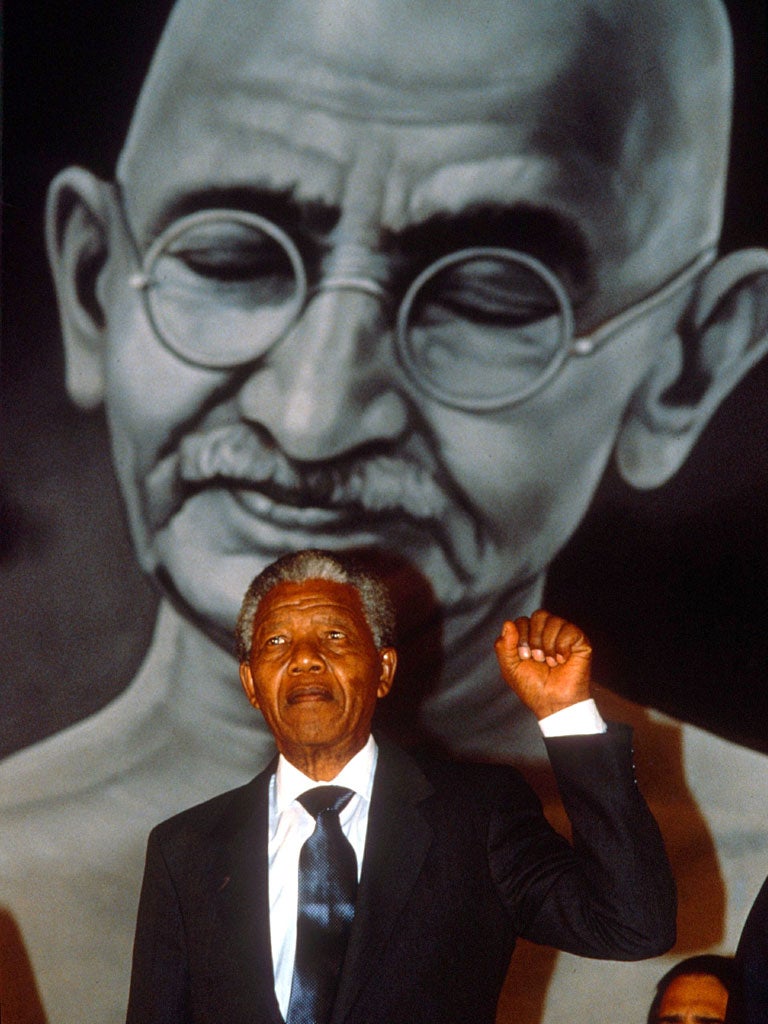

This is most evident in the relative lack of attention paid Gandhi’s racial blind spot: the fact that this campaigner for “non-white” British subjects’ rights had nothing to say about the absolute lack of rights of native Africans in colonial southern Africa. This leader who would set an important political example for a number of African and African-origin leaders, including Martin Luther King, Kenneth Kaunda and Nelson Mandela, did not himself, while in Africa, regard Africans as deserving of the same political rights as other oppressed people. Guha’s implication is that in Gandhi’s view the payback for his demands for Indians’ citizenship was an agreement to observe the racial status quo in other respects. Yet this was the same Gandhi who dedicated his whole life to the pursuit of “racial parity”.

A related oversight lies in the treatment of Gandhi’s legendary charisma. What was the magic radiating from this small man in a dhoti that raised a mass popular movement? The book’s argument that the key constituents of his anti-colonial politics were acquired and seasoned “as the iron framework of the South African racial state was fixed into place” is powerfully made, yet the charisma itself is left relatively unexplained. There has been some fascinating postcolonial analysis of how this radiance emerges from Gandhi’s creative exploitation of his own contradictions: of how, though averse to technology, he was as media-savvy as any 21st-century celebrity; of his loyalty to the British Empire in spite of his fierce critique of its methods. Like Mandela, who owes so much to Gandhi’s example, Gandhi’s radiance shimmers brightly through his deft manipulation of these multiple inconsistencies.

However, the numinous qualities of charisma are not Guha’s concern. His focus is on the journalistic, legal and activist practices that went into the making of Gandhi’s potent legacy of non-violence. The biography makes an especially important contribution not only in its grounding of these practices in new material, but also in its detailed tracing of those infinitesimal changes in Gandhi’s thinking on freedom that would transform for good the modern world’s agendas of resistance. It is ultimately not the myth of Gandhi, but his creation of a myth of India while in South Africa, that this book seeks to explain, and in this it triumphs. Gandhi before India is as exhaustively researched a biography of the African Gandhi as we will have for some time.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks