Trials of Passion: Crimes in the Name of Love and Madness by Lisa Appignanesi, book review

Three sensational court cases that take us from Brighton in 1870 to New York in 1906

The literary recreation of 19th-century show trials by writers such as Kate Summerscale and Kate Colquhoun has mined a rich seam of scandal and double standards behind the murders and divorce battles of Victorian Britain.

Lisa Appignanesi takes this exploration international in Trials of Passion, where she focuses on three sensational court cases in Brighton in 1870, Paris 1880 and the New York of 1906. The best of the crimes under examination are terrific. Christiana Edmunds is accused by her doctor, a man she loves and who may have been her lover, of trying to poison his wife. Edmunds becomes a veritable chemist to poison Brighton's supply of chocolate creams and have the finger of blame for the wife's sickness pointed away from herself and towards the shop that sells them. A boy dies as collateral damage. The circumstantial evidence against Edmunds seems compelling; the only question is whether she was bad or mad.

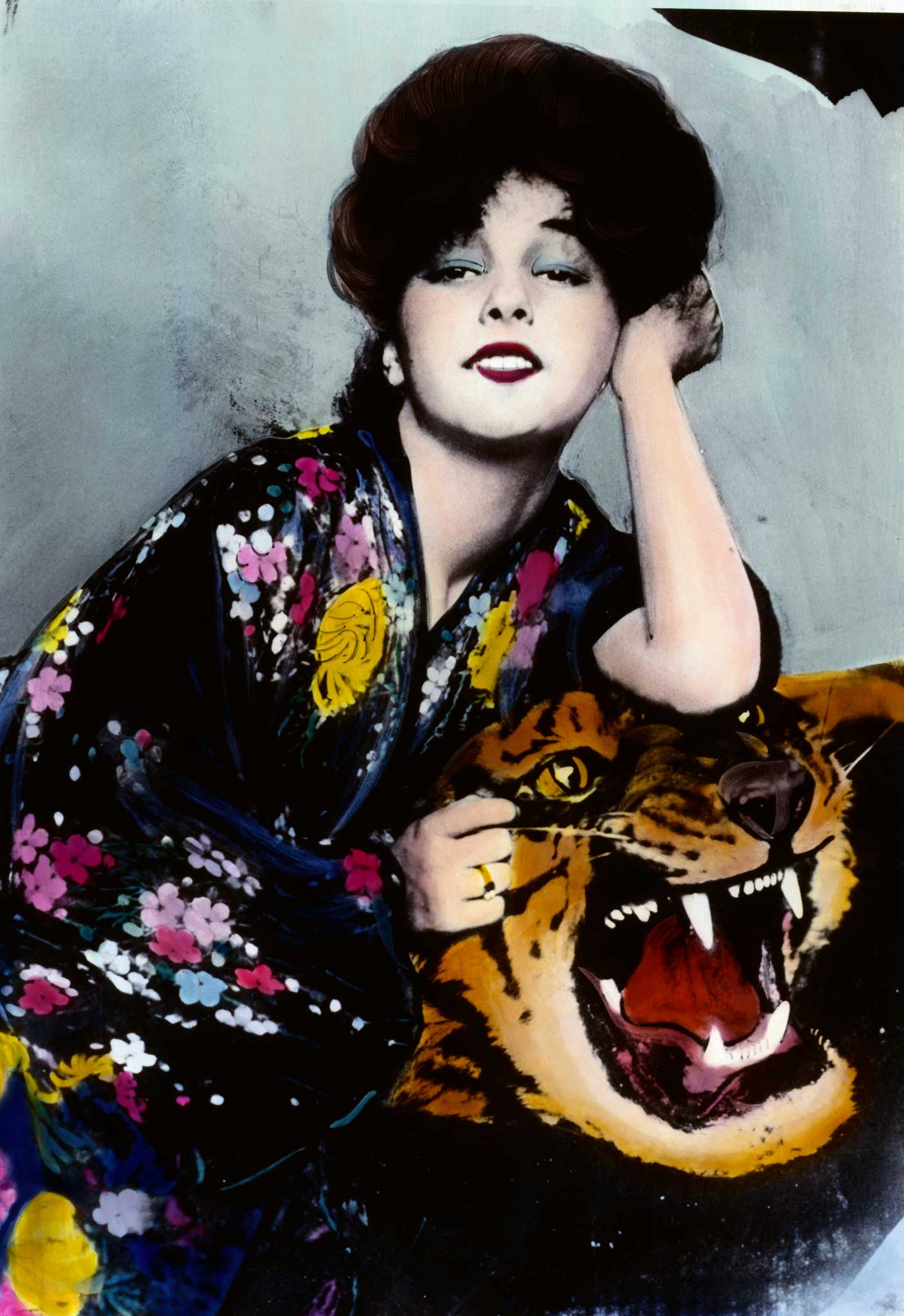

Similar questions marks hang over the cases that follow. French singer Marie Bière shoots her high-class lover after he treats her abominably and rejects their child. Millionaire Harry Thaw, a man with a penchant for whipping both young men and women, shoots dead the prominent architect Stanford White for having drugged and raped the teenage chorus girl Evelyn Nesbit – some time before Thaw beats and marries her himself.

Glorious detail is marshalled from the copious reporting of these sensational stories in the international media and a vivid picture emerges of the societal expectations and constraints for women whose innocence or guilt is often inextricably – if falsely – connected to their sexual morals.

But the problem arises in the explanation of what prompts the actions of Edmunds, Bière and Thaw. The author promises to investigate "where the 'madness' of love erupts into crime and whether medical-legal definitions of insanity can then prevail". But the definitions are often lacking and the author not always forensic. She sounds almost approving when she declares that the actions of Edmunds would have been treated as a crime of passion in France though surely few rational observers would condone murder for love. All the cases involve some claims of inherited insanity, yet there is a peculiar failure to explore which strands of madness do have a family risk factor – even if that evidence was unavailable to the Old Bailey more than a century ago.

And the declaration that "passionate love is, after all, ever a form of mental derangement from the norm" is so dramatic as to sound merely romantic without data from studies (which exist) to support it. Even then, is it a proper legal defence?

In her introduction, Appignanesi says Trials of Passion is a complement to her last two books so perhaps some of these questions are answered in her history of the "mind-doctoring profession" or her "anatomy of the unruly emotion that love is". But here, only in the case of Thaw (in the book's final quarter) is there a modern explanation of his probable mental state when World Health Organisation's classifications are cited to suggest he has a "paranoid personality disorder". Elsewhere, the lines between mad and bad seem blurred.

The author observes of the would-be Ronald Reagan assassin, John Hinckley, that his traits were those shared by many a rich teenager. But, evidently, not all rich teenagers try to kill. Appignanesi is a warm and clever writer – and a chair of the Freud Museum in London. But her fascination with the "mind-doctoring" sometimes proves more disruptive to a potentially gripping narrative than illuminating. She also writes novels. The Borgia of Brighton would make a fabulous subject.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments