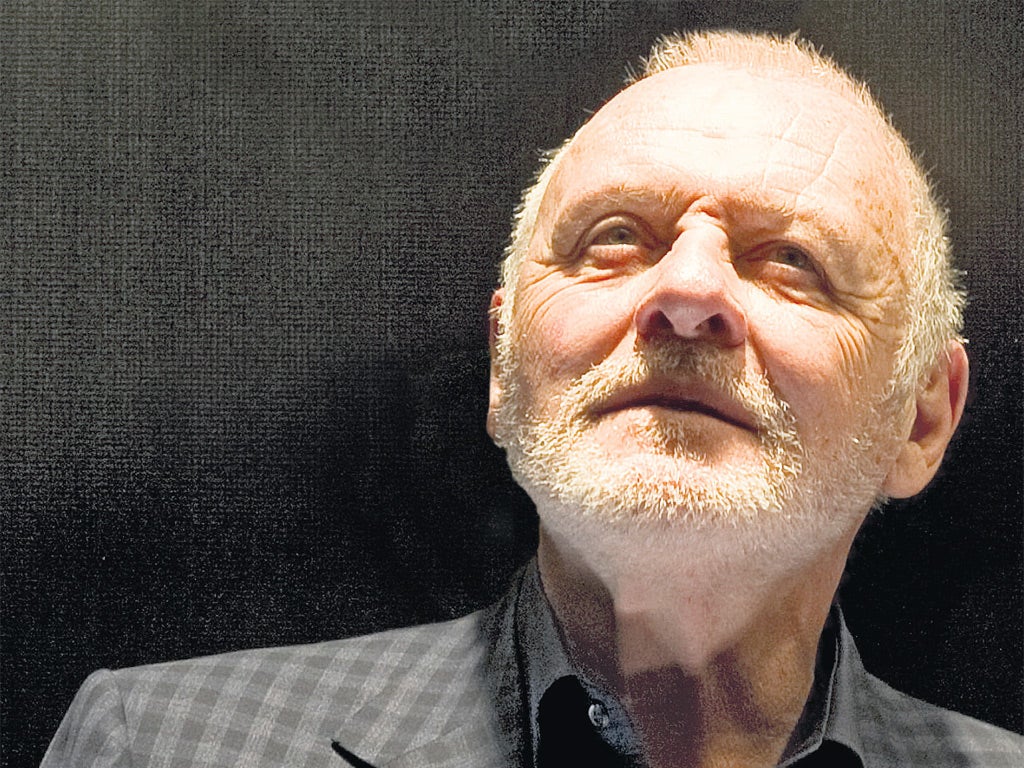

Anthony Hopkins: Hannibal hits the high notes with a classic performance

The Oscar-winning actor Anthony Hopkins has composed a collection of classical works. Many of the pieces are inspired by memories of his childhood in south Wales, he tells Jessica Duchen

Sir Anthony Hopkins is nothing if not versatile. From Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs to the repressed butler in The Remains of the Day, from Surviving Picasso to C S Lewis in Shadowlands, he has tackled a range of mesmerising characters. But now he has taken on perhaps his most startling incarnation to date: he has become a composer.

A recording of orchestral music written by Hopkins is being released this month through Classic FM. Some of the pieces have already been aired in his films Slipstream and August, while others are being disseminated here widely for the first time. This development would seem a bizarre twist in anybody's tale, let alone that of one of Britain's best-loved actors – but Hopkins affably hands chief credit for it all to his wife, Stella. She it was, he says, who provided the impetus to make his lifelong musical leanings public.

"Stella has been quite an inspiration," Hopkins says. "She's encouraged me to expand and broaden my fields of outlook, both with painting and with music." It was her support that also persuaded him to exhibit some of his artworks about two years ago.

"I have a piano – I play every day, if I'm home – and I've always improvised music and composed," he says. "But I never took any of it seriously. I did it not out of ambition to be a musician or to be a composer, but for the sheer pleasure of it. Stella heard my playing over the years and said, 'Why don't you write those down?'" In some cases he had already done so.

The pieces come quite easily to him, he says: "That's because I don't worry about it. I don't think, 'I've got to get this perfect, I've got to analyse it...' If it sounds OK to me and other people like it, then I go ahead." He does not have a musical role model or ideal: "I have catholic tastes and no preconceptions. I love listening to Vaughan Williams, Delius and Elgar, but I also listen to country and western music and jazz. I listen to anything."

In spirit, his music turns out to be rather similar to his paintings: vividly coloured, drifting from the literal to the surreal or dreamlike and sometimes betraying a dark, almost haunted intensity. The opening track, Orpheus, is positively sinister. But there's quite a variety. One tender number featuring a rhapsodic cello solo is dedicated to Stella; some pay tribute to the visceral excitement of the cinema, while And The Waltz Goes On – a full-blooded, slightly lurid take on the Viennese waltz tradition – has been championed by the ever-popular André Rieu, who orchestrated it and gave its first performances with his Johann Strauss Orchestra.

Many of the pieces, though, are gentler and full of nostalgia, intimately bound up with his childhood in Wales, where he was born in 1937. They feel distinctly filmic, as if Hopkins is creating a soundtrack for his memories.

"The post-war years were pretty awful all over Europe," he recalls. "Everything was devastated and Britain was going through a terrible period of austerity, greyness and drabness. Everyone was trying to scrape a living, just to recover. My father, who was a baker, was working hard and my mother was trying to keep everything together. But I was a little boy and as children we're not concerned about things like that – all we want to do is go out and play, or chase about the fields. So I look at that as a kind of Eden, a beautiful, idyllic time – but when you look at the reality, it was nothing but poverty and grind."

Hopkins discovered music before he ever thought of attempting acting. "I was a lonely kid because at school I was a real duffer," he declares. "I was completely stupid, I didn't know what on earth was going on, so I withdrew into myself. I didn't have any friends at school and I never played with other kids. I sort of created my own world. It sounds a little bit like a fairy tale, but I had no other choice. I could draw and I could play the piano. And that has stayed with me all my life."

Does he think there is a connection, on a creative level, between music and acting? It's not the art forms that are so similar, perhaps, as his attitude to them. "When I'm preparing a role I learn my lines very methodically – I go over and over them until the images of the character I'm going to play become clear," he says. "Then I go on the set and hope it'll work out, and if it does, it's fine, as long as I am relaxed and as long as I am prepared. With music it's the same: I play the piano a lot, but I don't set out with any goals. I've got the attention span of a bumblebee. I'm a great starter, but I never finish anything. It's a kind of free and easy, haphazard way of existence, but that's the way it is; that's the way I was born. As a young actor I would have looked at it as a bit of a curse, but in fact it's given me tremendous freedom."

Ambition, he says, had nothing to do with it. "I don't think the human mind works in set patterns or goals. Thinking, desires and dreams are pretty amorphous – they're like vapours and clouds that drift around in our heads, certainly in mine – so I never form plans. And it's very similar with acting. I didn't have a set idea that I was going to become an actor. I had no idea what I was going to become – I thought I'd end up in the steelworks in Port Talbot for the rest of my life. But by chance I saw a scholarship advertised in the Western Mail to the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, and I applied for it and got it. I'd never acted in my life before.

"I wanted to be a musician, but I didn't have that skill or the requisite academic background, so I became an actor instead by default. I never really belonged in this business. I worked in the National Theatre and I never felt at home there, working with other actors. And that's been the story of my life. But it's all been pretty good, really, because it's created my life for me, that psychological mindset – and music came along."

Last year the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra gave several concerts including Hopkins's pieces; the disc features live recordings from those performances, conducted by Michael Seal and produced by Tommy Pearson. The concerts, Hopkins says, were his most satisfying musical moments to date: "They were terrific, especially the one in Cardiff with a Welsh audience." As for the CD, he adds, "I'm thrilled with it."

But he doesn't care too much about how other people are likely to receive his music. "Because I don't have any set notion of what the results will be like or what people will say of them, I'm free of all that. What are they going to do? Put me in jail if it doesn't work? I don't worry about it. Music has been, through the encouragement of my wife, a whole new world."

'Anthony Hopkins – Composer' is released by Classic FM on 16 January.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks