Music wars: In the mood

Although it was used as a propaganda tool, music helped those enduring the horrors of the Second World War, says Patrick Bade in a new book

Four years ago a pile of Second World War Pyral discs turned up mysteriously in a junk shop in Lyons. They came from the archive of the notorious Nazi-controlled Radio Paris. The premises of Radio Paris had been torched during the liberation of the city and no one knows how these discs had escaped the conflagration or why they had turned up in Lyons more than 60 years later.

In remarkably vivid sound the discs preserve two concerts that had been broadcast live from the Théâtre des Champs Elysées in January 1944. The concerts were free and ordinary Parisians mingled with members of the German Wehrmacht in their grey-green uniforms. What is evident in these recordings is the heightened response to music in wartime and the palpably shared emotion of musicians and audience, of oppressed and oppressors. The musicians of the Grand Orchestre de Radio had been picked from the other Paris orchestras and were the best that France had to offer. The conductor was the Dutch Willem Mengelberg – a revered musical figure before the war but later tainted by accusations of collaboration with the Nazis. He would conduct for the last time six months later (Beethoven's Ninth Symphony) in the same theatre with the allied armies already hurtling across Normandy on their way to Paris.

Most poignant of all is the highly charged performance of Tchaikovsky's Symphonie Pathétique given on 20 January, the day after the German siege of Leningrad had been broken. It is likely that the French civilians, glued to their clandestine radio sets at night to listen to BBC news bulletins, were better informed about the latest events than the Germans. But by January 1944 every member of the audience must have been aware that the end game had started and that their fates would be decided in the coming months. Under these circumstances Tchaikovsky's baleful utterances must have sounded more urgent than ever.

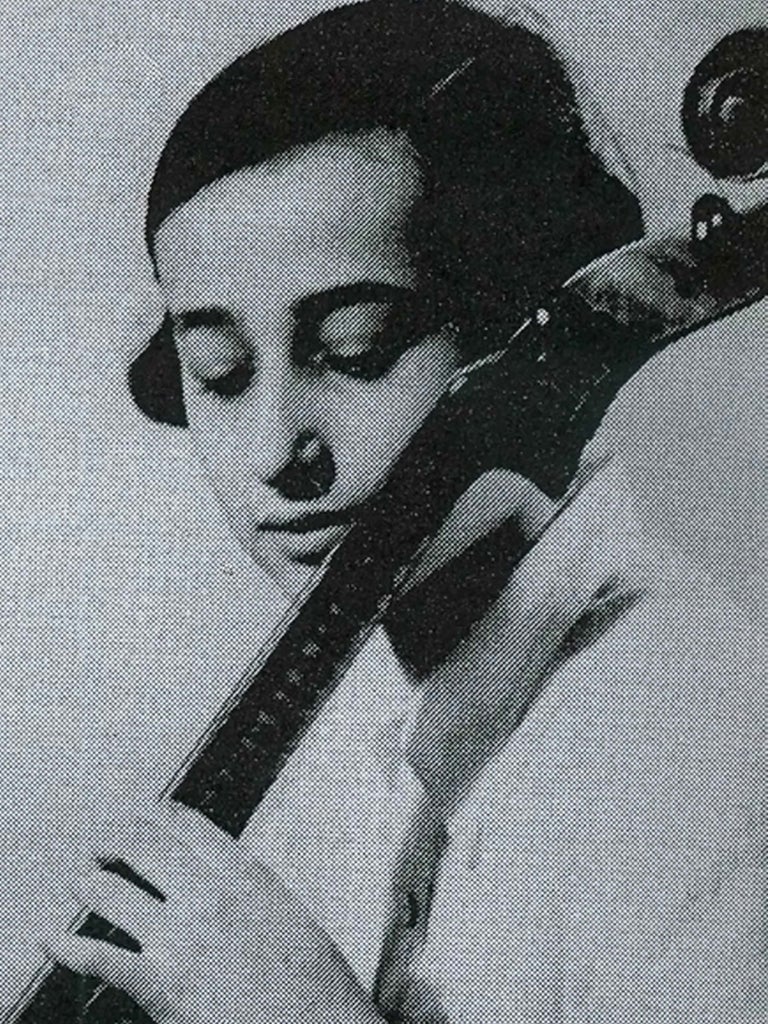

Anyone who lived through the war will have powerful memories associated with music, whether it was Beethoven or Glenn Miller. My father never forgot the emotion he felt when he heard the voice of Vera Lynn emanating from a radio set in a remote area of Persia. Musical sensibility was sharpened by what Noel Coward described as "the enforced contact with the sterner realities of life and death." In her autobiography Joyce Grenfell spoke of being "nourished" by music. Listening to a performance of Mozart's clarinet quintet at one of Myra Hess' famous National Gallery concerts in 1940, Grenfell had a "glimpse of unchanging limitless life, of spiritual being that no war or misery of uncertainty and fear could ever touch." Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, the cellist of the women's orchestra in Auschwitz, used strikingly similar language to describe her reaction to taking part in a string quartet arrangement of Beethoven's Pathétique Sonata. "We were able to raise ourselves high above the inferno of Auschwitz into spheres where we could not be touched by the degradation of concentration camp existence."

The Nazis laid more emphasis than the Allies on "high culture" and the tradition of Austro-German classical music was central to their self-image. Britain was dismissed as "das land ohne musik" (the country without music). Stung by Nazi accusations of philistinism, the BBC countered with a broadcast featuring the actor Marius Goring and the pianist Myra Hess billed as "Britain's reply to Goebbels by Goring and Hess".

Both sides exploited the morale boosting value of music. Radio was one of the most powerful weapons of the war and music both popular and classical was deemed essential to attract listeners. Nowhere was this more crucial than in the Middle East where millions of Arabs of dubious loyalty to their colonial masters listened to the Thursday evening broadcasts of the great Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum on the pro-British Cairo Radio. Umm Kulthum might have been the only woman who could have lost the war for the Allies had she changed allegiance and persuaded the Arab masses to follow her. Music also played a small but significant role in the battle for Stalingrad in the winter of 1942-3, which marked the turning point of the war. The Russians tried to demoralise the trapped German troops by bombarding them with nostalgic German songs from loud-speaker vans. Ironically, Goebbels succeeded in demoralising them more effectively still with faked broadcasts of Christmas carols, which he claimed came from within the besieged city. Some of the cruder attempts at musical propaganda were probably counter-productive. Charlie Schwedler who crooned Nazi propaganda in heavily accented English to melodies of popular American songs accompanied by an accomplished and sophisticated jazz band can only have raised laughs of an unintended kind. Glenn Miller's more laid-back approach paid better dividends if only in persuading Germans that it might be more comfortable to surrender to the Americans than to wait for the Russians.

On the popular music front the Americans won the war before it began. Though jazz and swing were reviled by the Nazis as counter to the German ideal, Goebbels realised that the desire to dance to American-style music was a force better harnessed than resisted. Gypsy music was also too popular to suppress, even if the Gypsies themselves were destined for extermination.

Apart from swing, the other popular musical form during the war was operetta. The suspicion among Hitler's inner circle was that he secretly preferred The Merry Widow to Götterdämmerung. But operetta was particularly problematic to the Nazis because so many of the composers, librettists and performers of operetta were Jewish. Johann Strauss's birth certificate had to be doctored to suppress evidence of his Jewish ancestry and there was a mass exodus of operetta composers and singers to the United States. The most famous of all, Franz Lehar, remained under the personal protection of Goebbels and succeeded in saving the life of his wife but not of his favourite librettist Fritz Löhner-Beda, who died in Auschwitz in 1942.

In a tribute to the conductor Bruno Walter, Thomas Mann commented on the dual nature of music "...it is both moral code and seduction, sobriety and drunkenness, a summons to the highest alertness and a lure to the sweetest sleep of enchantment, reason and anti-reason." Popular songs and more serious music too, could change meaning in the light of political events, could even change allegiance and jump enemy lines. Beethoven was claimed by both sides. He was by far the most performed composer (followed at some distance by Wagner) in the wartime Prom concerts that together with Myra Hess' National Gallery concerts became such an important symbol of British resistance. The British were quick to appropriate the opening four note motto theme of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony which conveniently formed the letter V in Morse code. Despite their best efforts the Germans never re-appropriated this music and it remained stubbornly associated with the Allied war effort.

The most famous example of a song crossing sides is "Lili Marleen", which was adopted as the song of the British Eighth Army and performed and recorded in countless different languages. The Merry Widow did good service to both sides, too, enjoying long runs in New York and London and touring to Cairo and Tel Aviv. Most confusing of all was the fate of Madama Butterfly. Puccini's opera was banned in New York for the duration of the war as it was not thought appropriate to represent an American naval officer mistreating a Japanese woman. In Marseilles performances scheduled for the beginning of 1943 were suppressed by the occupying Germans who feared that Puccini's musical quotation of the Star-Spangled Banner might provoke a demonstration so soon after the American "Torch" landings in North Africa. But in Germany and Britain Madama Butterfly was more widely performed than ever. Despite being at war with Japan, the British took the Japanese heroine to their hearts, although the statuesque Australian soprano Joan Hammond attracted astonished glances when she tottered across Glasgow railway station still dressed in her kimono when trying to catch the last train back to London after a performance. It would seem that Puccini's masterpiece even touched the heart of the monstrous Maria Mandel who ran the women's camp at Auschwitz, and who liked to be soothed with selections from the opera after her arduous work of mass murder.

Music is morally neutral. In the Second World War it was used for good and evil purposes. At no other time was music's power as a weapon and as a solace more vividly demonstrated.

'Music Wars' by Patrick Bade (East and West Publishing). The Mengelberg concerts are on Malibran-Music (malibran.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks