Sergei Prokofiev: Beyond 'Peter and the Wolf' – the rehabilitation of Stalin's composer

Prokofiev followed 'the bitch goddess success' back to Soviet Moscow – or so the story goes. Think again, Vladimir Jurowski tells Andrew Stewart

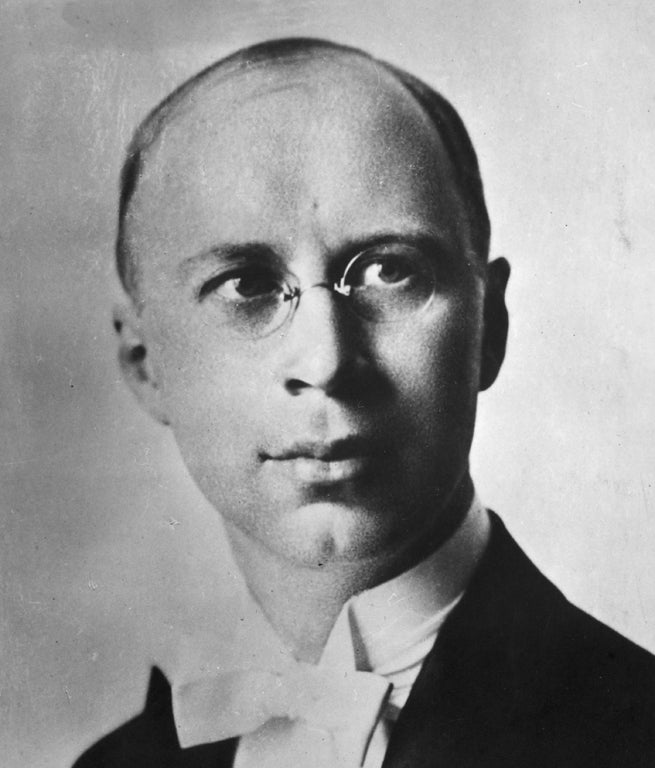

Soviet photographers did little to soften the image of Sergei Prokofiev. The composer's oval face always appears aloof, his gaze fixed high above the cares of comrade workers.

Western commentators saw the pictures and found fault. They questioned Prokofiev's decision to return in 1936 from exile in Paris to the Russia of inhuman five-year plans, show trials and summary executions. And many struggled to reconcile the composer of modernist masterworks and mainstays of the classical concert repertoire with the man responsible for Zdravitsa, a birthday "toast" to Joseph Stalin penned shortly after the Soviet Union invaded Poland in September 1939.

Despite impressive revisionist work by recent scholars and performers, Prokofiev's posthumous reputation still carries the burden of Cold War criticisms, Stalinist censure and myopic misinterpretation. Igor Stravinsky, first among Russian émigré composers, set the tone by mocking his younger colleague's Moscow move: "He followed the bitch goddess success, nothing else".

Vladimir Jurowski, principal conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, is determined to cut through the fog of received wisdom to reveal a richer, more human picture of Prokofiev's life and art. The Russian musician's latest Southbank Centre festival, which unfolds from Friday to 1 February, offers a 14-date programme of concerts, lectures and interlinked events. Prokofiev – Man of the People? casts its question mark over the composer's creative development to interrogate the complexities of his final years in Stalin's evil empire.

Fate determined that Prokofiev and Stalin should die on the same day – 5 March 1953. The composer's funeral, attended by 40 friends and family members, was hastily conducted a few hours before the great spectacle of Stalin's state ceremony. Prokofiev stole Soviet headlines a decade later, his posthumous reputation eclipsing coverage of the disgraced dictator. Jurowski believes that Prokofiev's genius has been overshadowed in Britain by concerns that his move to the Soviet Union amounted to a sell-out, an artist's pact with the devil.

The reasons for the move, notes the conductor, were many and complex, although homesickness clearly played a significant part. "It is like this: foreign air is not conducive to my inspiration, because I am Russian," Prokofiev supposedly said in 1933. "I must go back ... I must talk to people who are of my own flesh and blood."

Jurowski's festival offers pieces rarely heard in concert, assembled to chart Prokofiev's natural evolution from a prodigy of Tsarist times and avant-garde experimenter to the creator of melodious scores for the masses. The programme explores everything from pre-1917 songs and the steel-edged Second Symphony to Prokofiev's incidental music to Egyptian Nights, Alexander Tairov's 1934 play based on words by Pushkin, Shakespeare and Shaw.

The festival also presents the world premiere of the oratorio version of Prokofiev's music to Sergei Eisenstein's epic film Ivan the Terrible, smartly fashioned by Levon Atovmyan and subsequently buried by Soviet politics, and a "classical club night" curated by Gabriel Prokofiev, the composer's grandson.

"The purpose is to examine Prokofiev with fresh eyes and ears," Jurowski tells me when we meet in London. His proposition amounts to a personal campaign. The conductor's paternal grandfather (also Vladimir) studied composition with Prokofiev's colleague Nikolai Myas-kovsky and witnessed the state's post-war denunciation of both men's work, together with that of Shostakovich and other leading Soviet composers.

"Prokofiev knew my grandfather very well," Jurowski recalls. "And he knew his music." Was he tempted to include an example of the latter in the London Philharmonic's Prokofiev festival? "I started from afar, as it were, by performing Myaskovsky's Sixth Symphony with the LPO. Maybe one day I will be brave enough to perform the music of another Vladimir Jurowski." For now his mission is to show the breadth of Prokofiev's work and underline its contemporary relevance.

"It is time to reconsider Prokofiev's importance to the development of music since he died in 1953. His position in the musical world's consciousness was once sharply divided between the popular composer of Peter and the Wolf and the image, propagated by the post-war Darmstadt group of composers, of a third-rate artist. Pierre Boulez and his very influential circle felt that Prokofiev was not to be taken seriously. Those judgements must be challenged."

Jurowski cites the composer's enduring influence, to be heard not least in the music of John Adams, Louis Andriessen and Alfred Schnittke. "We should thank Prokofiev for creating aspects of musical postmodernism and minimalism. And today's Hollywood composers should erect a monument to him for the ideas he gave them!"

Jurowski's desire to propagate a "better understanding" of Prokofiev rests on secure foundations. The 39-year-old conductor began studying the composer before moving from Moscow to Germany in 1990.

"I was interested in Prokofiev because of the apparent contradiction between the coolness of the person, often proclaimed as showing a lack of empathy for others, and his incredibly warm-hearted, very human music, especially in the work of his later years.

"And there's another compelling contradiction between the cutting-edge modernism of his youth and the seeming simplicity of his Soviet era works. Was this some kind of toll paid at Stalin's front gate to gain access to his motherland? Or was this the genuine response of a composer searching for greater depth? We shall see whether we can pass through these contradictions to reach Prokofiev's persona."

While Jurowski is set to conduct five of the festival's concerts, Alexander Vedernikov and Yannick Nézet-Séguin will direct one programme apiece. Vedernikov, who quit as the Bolshoi Theatre's music director in 2009 as a protest against the company's management, was schooled in Prokofiev's music by his father, a leading operatic bass in Soviet Russia. His concert, opening the series this Friday, includes the Seventh Symphony, a late retreat from the confident brilliance of its composer's early Soviet works. The symphony's first conductor persuaded Prokofiev to write an alternative ending, sufficiently upbeat to please members of the Stalin Prize Committee.

"You can sense from beginning to end a sleepy bitterness in the music," notes Vedernikov. "It's not important which of the endings you use – nothing changes that bitterness. This is a special case in music history where a composer, accused of being too removed from the taste of the common people, honestly simplified his style but still expressed the personal feelings of his final years."

Vladimir Jurowski recalls hearing childhood tales about Soviet cultural politics from his conductor father and composer grandfather. He also read the report of the first Congress of the Union of Soviet Composers in 1948, in which Stalin's apparatchik Andrei Zhdanov "uncovered" a conspiracy by Prokofiev, Shostakovich and others to impose so-called formalist tendencies on their colleagues. Prokofiev's name was added to the long list of enemies of the people; many of his works were proscribed, his livelihood curtailed. "My grandfather received a copy of the report, which I read as a child. That was one book I wasn't allowed to take to school!"

He notes that Tikhon Khrennikov, Stalin's duplicitous mouthpiece as general secretary of the Composers' Union, privately aided the Jurowski family following his grandfather's unexpected death. "Khrennikov did everything in his power to ban my grandfather's music during and after his lifetime, so there was this animosity between them. And yet he still helped my father find work."

For Jurowski, it is impossible to interpret the ambiguities of Soviet life without analysing its art. "And you cannot understand the art of the time without analysing its political and social background." He points to the "ambiguities" built in to Prokofiev's Ode to the End of the War. "Yes, it's about jubilation. But there's irony in its use of eight harps, three saxophones and four pianos." The conductor suggests that the aural extravaganza's meaning would not have been lost on an audience subsisting on starvation rations just months after Hitler's defeat. "And here is Prokofiev employing the elements of jazz, of American bourgeois music, in a piece intended to celebrate the Soviet people's great victory."

Jurowski hears the eloquent melodies of Prokofiev's final years, clearly present in the ballet Cinderella, the sixth and seventh symphonies and the Cello Sonata, as "deeds of individual heroism", the personal creations of a composer denounced and deprived by Stalin's collectivist state.

"Music in those times was much more than simply art: for many, it was a tool of spiritual resistance and survival." He pauses to consider whether Prokofiev's music can ever connect as intensely with today's listeners as it did with Soviet audiences.

"We must at least address the meaning of why this music mattered so much then, to speak it out, especially to a younger generation. I want people to hear Prokofiev with open ears in the hope that his work can touch hearts now as much as it did during his lifetime."

'Sergei Prokofiev: Man of the People?' Friday to 1 Feb, southbankcentre.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments