Actus Tragicus, International Festival, Edinburgh<br/>London Sinfonietta, Kings Place, London

In the mean rooms of a rambling residence, the characters in a staged cycle of Bach cantatas pursue circular lives

For Bach, Actus Tragicus (BWV 106) ended with a Gloria: sweet and resolute, gilded with melismatic Amens, and sealed with a chaste kiss of a cadence from two treble recorders. For the late director-designer Herbert Wernicke, whose staged cycle of six Bach cantatas takes its name from this work, it ends with a repeat of the fifth movement: an intricately wrought memento mori of chastising aria and solemn chorale, trudging bass and sighing viols.

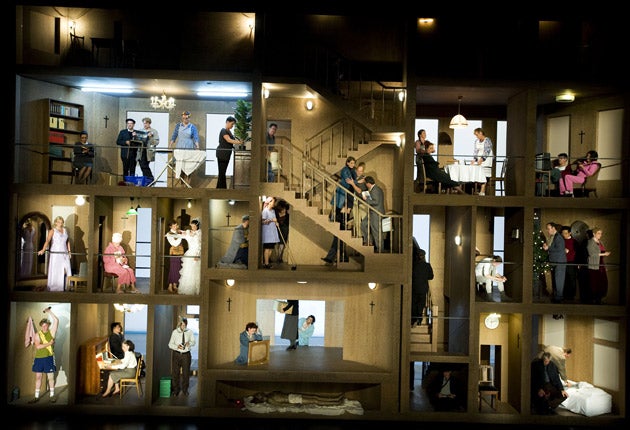

Abandoned by its residents, the four-storey elevation that fills the stage is empty, save for the Christ figure that lies in the cellar, lit by a votive candle. A desolate cry from the soprano soloist ("Ja, komm, Herr Jesu, komm!") is the last thing we hear, unresolved, unanswered and, as it was 10 minutes earlier, out of time with the cello.

First performed by Staatsoper Stuttgart in 2006, Actus Tragicus is a bleak dance between the divine and the mundane, the extraordinary and the commonplace. As the admonitory recitatives and beguiling obbligato arias of BWV 178, 27, 25, 26, 179 and 106 morph into one supercantata, the inhabitants of an apartment building go about their business. On the third floor, a woman in curlers (counter-tenor Kai Wessel) is ironing, while her obsessive-complusive husband (Michael Nowak) checks his watch. Across the stairwell, a couple sit down to dinner with their sulky teenage daughter, while their shell-suited neighbours bicker over the remote control. A diva (Simone Schneider) tries on a series of dresses. A bride runs away, ignored by the cleaner, the surveyor (Martin Petzold), the illegal immigrant, the drunk, the canoodling lovers. There are more lovers downstairs, taking their turn on the rumpled bed where bass soloist Shigeo Ishino will be pronounced dead, approximately seven times. A few rooms away, a suicide tests the strength of his noose, while next door's sports jock does bicep curls. The postman comes and goes, Santa too, while a man in a beret hangs crucifixes on the walls, then takes them down again. Death, in a Michael Jackson fedora, pauses to touch an arm or hand. Presents are exchanged, babies nursed, bins emptied, coffins removed. It's Groundhog Day with basso continuo.

The somnambulant sequence of movements is briefly shattered as Petzold reels at the sight of a cross ("Schweig nur, taumelnde Vernunft!") and as the chorus huddles in the basement ("Welt, ade!"). There are vivid performances from Petzold, Ishino and Schneider, curdled ones from Wessel and Nowak, but the music, which begins after nine minutes of dumb-show, is compromised both by the set and the orchestra. Under Michael Hofstetter's beat, too many corners were turned lazily, with the organ lagging behind the off-key archlutes. At certain points, you could see the potential for Wernicke's concept to be as redemptive or provocative as, say, Peter Sellars' "Ich habe genug" (BWV82). Sadly, Stuttgart has no singers to rival Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, nor players to rival the Emmanuel Orchestra.

At Kings Place, the opening festival of the 2009/10 season was jubilant with the chimes of toy pianos. Who can fault a venue where instead of being told not to touch the instruments, you are invited to touch them gently? Between Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven, Indian classical music, a hog roast and the toy pianos, it was difficult to know where to turn. But in Hall Two, trombonist David Purser, clarinettist Mark ven der Wiel, violinists David Alberman and Joan Atherton, flautist Michael Cox, harpist Helen Tunstall and viola-player Fiona Bonds of London Sinfonietta offered two informal taster programmes of Berio, Debussy and Takemitsu.

Now, informality is as unfakeable as sex appeal and I could have done without Sara Mohr-Pietsch's Blue Peter-ish introduction. (Surely any London Sinfonietta audience will have heard of La Mer?) Still, the aphoristic lyricism of Takemitsu's And then I knew 'twas Wind and comfortable melancholy of Debussy's Sonata for Flute, Viola and Harp turned a dry black box into a shady garden, while van der Wiel, Purser, Alberman and Atherton revealed that Berio had achieved in his Sequenzas what Staatsoper Stuttgart could not: a portrait of humanity at its silliest and greatest, heroic, bathetic, vexed and elated.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies