Doreen Valiente: The fascinating story of the mother of modern witchcraft

Doreen Valiente's work is being celebrated at a new exhibition in Brighton

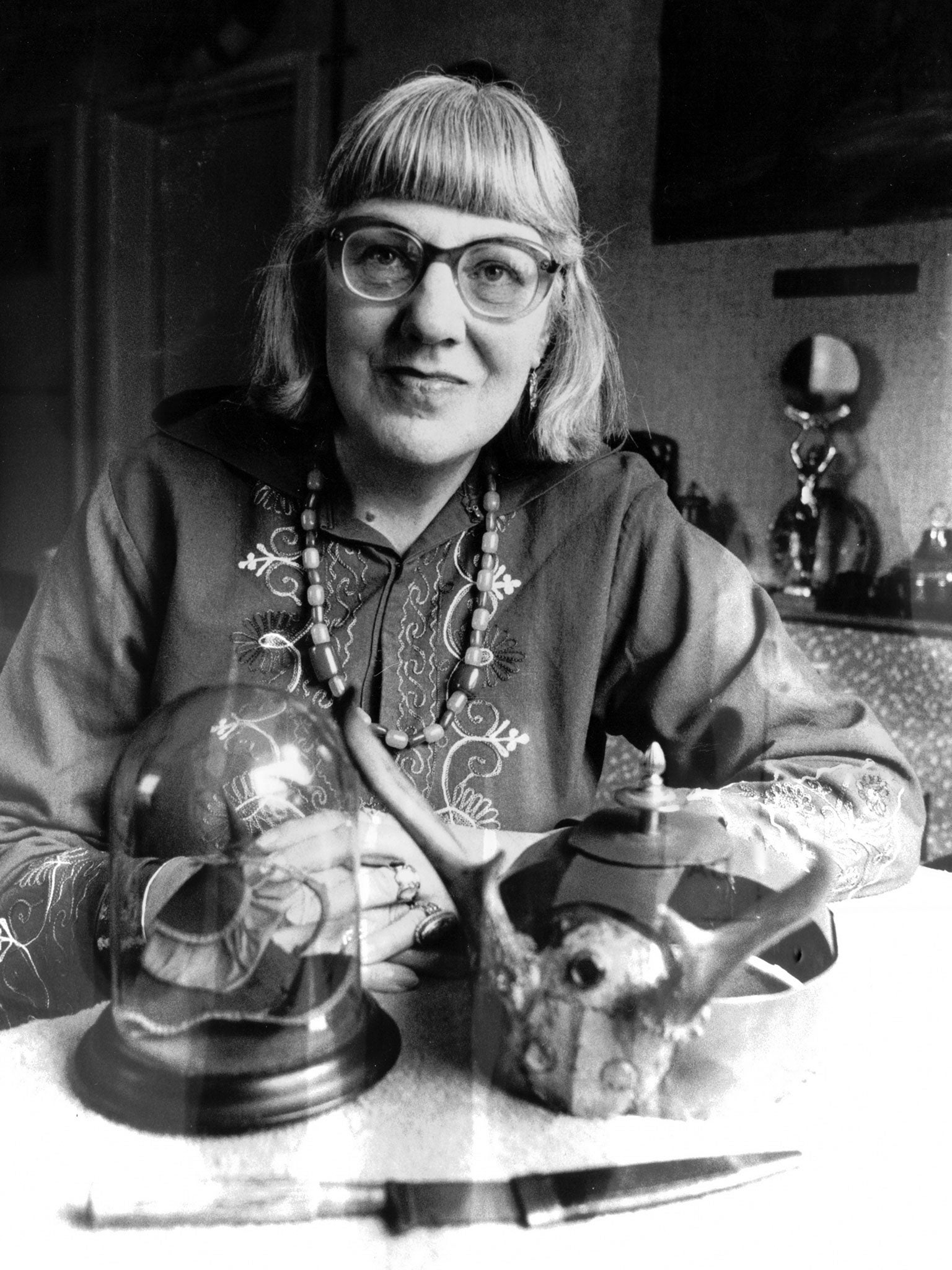

Doreen Valiente, the mother of modern witchcraft, was nine-years-old when she had what she called an indescribably mystical experience, and saw the veil of reality tremble.

On a balmy summer evening in the 1920s, she crept into her south London garden at twilight and was consumed by the feeling that her surroundings were fabricated to hide something else: something “very potent.”

Her parents were probably right, then, to wonder whether she was interested in the occult when she began careering around her neighbourhood on the household broomstick, and packed her off to a convent school.

Aged 15, she left the school and refused to go back. Inspired by the books she found in her local library, she became fascinated by witchcraft.

Decades later, Valiente was one of the most important figures in Wicca – believed to be the first fully-formed new religion to appear in England and spread across the world – by writing down much of its liturgy, and helping to lift a ban on witchcraft which had been in place for over two centuries.

With high-street stores currently filled with mass-produced pentagram rings, mysterious-looking black clothing and rugged amethyst jewellery, it is hard to imagine that Paganism, and subsets such as Wicca, was ever banned in the UK.

So, a new exhibition at Preston Manor in her hometown of Brighton exploring her role in Wicca is particularly timely for contextualising now ubiquitous symbols and ‘witchy’ fashions.

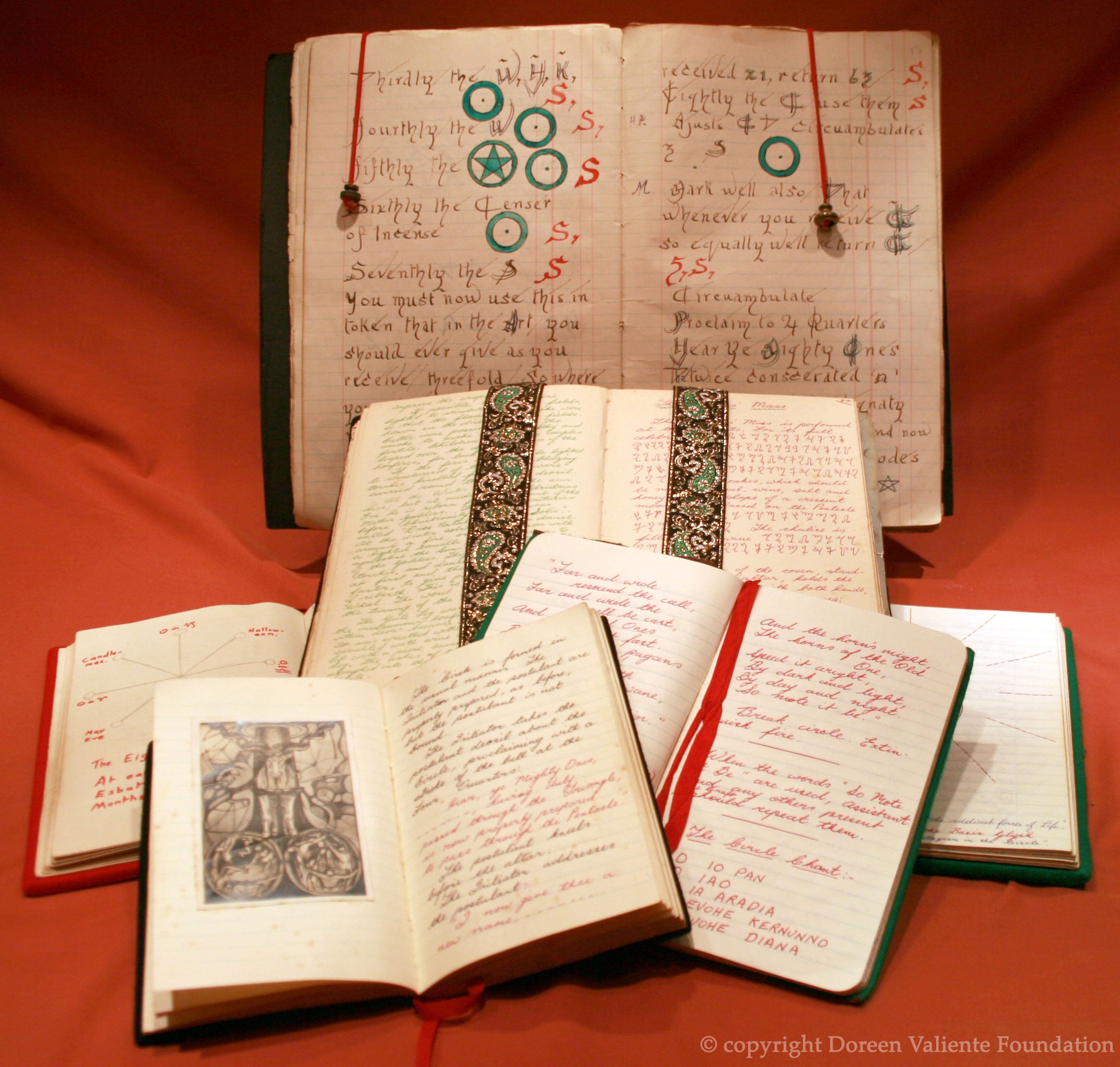

The exhibit also showcases her extensive collection of Wiccan and occult artefacts that is believed to be the most important of its kind in the world, which includes Tarot cards, a witch’s ceremonial knife called an Athame, and two glass curse bottles.

Valiente was raised in the hangover of Europe’s fin de siècle, when science and religion were at a loggerheads, and ideas of green politics, individualism and women’s rights which dominated sub-cultural movements in the 1960s and 1970s began to germinate.

“Wicca comes from a growing need for feminism, environmentalism and freedom of individual choice. Traditional religion in Britain was not very satisfying on all three counts,” explains Ronald Hutton, Professor of history at Bristol University.

Born in 1922, Valiente also worked as a translator at Bletchley Park during World War II.

“She was clearly able to keep a secret and used this ability in her subsequent writings on witchcraft,” says Philip Heselton, Valiente’s biographer.

Categorised under the umbrella-term paganism, Wicca celebrates and ritualises the rhythms and cycles of the natural world and the human participants in those processes, explains Dr Paul Reid-Bowen Senior Lecturer in Religions, Philosophies and Ethics at Bath Spa University.

These beliefs are encapsulated in the Wiccan Rede: “An it harm none, do what you will.”

The exhibition also features an ivory wand from Gerald Gardner, who is widely recognised as the founder of Wicca. He was initiated into a coven at the edge of the New Forest in 1939 when Valiente was still a teenager, and began to write his own interpretations of ancient pagan witchcraft.

Valiente first became aware of Gardner by reading about him in a magazine article, and decided to contact him. By the mid-1950s, Gardner appointed her as the High Priestess of the coven he founded - one of the highest positions in Wicca.

“Gardner was important for Valiente in so far as he actively encouraged her to contribute to the development and writing of Wiccan rituals and ceremonies, and also promoted her as a public-facing representative of Wicca,“ says Dr Bowen-Reid.

“In a religion where initiation and lineage were so important, it is also noteworthy that Valiente’s early association with Gardnerian Wicca granted her a certain authority.“

While Gardner interpreted ancient rites and rituals, Valiente documented them with poetic fervour, explains Ashley Mortimer, a founding trustee of the Doreen Valiente Foundation and curator of the exhibition in Brighton.

“She gave the modern Craft a robust religious litany and a logical framework. It was this that allowed it to be more easily passed on through initiation and is probably the reason it spread so firmly and rapidly and continues to expand across the world today,” believes Mortimer, who is also the director of the Centre For Pagan Studies.

“Valiente put flesh on the bones of the written witch lore that Gardner had shown her.“

Explaining his approach to piecing together the exhibit, he adds: “We wanted to show that the rise of Wicca with Doreen and Gerald provides a bridge to the deep past but also a link to the present and future of Paganism in our society and culture.”

Doreen provides a bridge to the deep past but also a link to the present and future of Paganism

But Valiente did not simply help to refine Gardner’s ideas. She was a pivotal figure in Wicca and paganism in her own right.

“Valiente was one of the creative pioneers and personalities of modern Wicca who helped raise public awareness and bring the religion to maturity,” says Dr Bowen-Reid.

“Had Valeinte not been Gardner’s High Priestess, Wicca would almost certainly be very different and may even not have survived into today's world,” says Pagan Federation president Mike Stygal, which Valiente helped to found in 1971.

In her lifetime, Valiente penned many important books including An ABC of Witchcraft, The Rebirth of Witchcraft, and Witchcraft for Tomorrow - which Heselton describes as her Magnum Opus.

Dr Reid-Bowen, however, argues that Valiente’s most important work was the Charge of the Goddess, a poetic invocation of the female deity that is used in almost all Wiccan and many other Pagan ceremonies across the world.

And as a woman, and the links that affords to the Goddess from whose womb Wiccans believe all things came, Valiente perhaps found an added level of respect in the religion.

“The feminine divine principle, personified as the great Goddess, was revered and worshipped long before her male counterpart,” explains Mortimer.

While early Wicca was dominated by strong male personalities, and patriarchal religions have dominated the world for centuries, experts agree that the rise of feminism in the 1970s redressed the balance in the new form of paganism.

“Certainly Doreen was a strong supporter of women's rights and wrote about feminism in her books as well as speaking up for feminist issues throughout her life,” says Mortimer.

Such attitudes therefore attract young women in particular to the religion, as evidenced by interviews carried out with Wiccan witches by Professor Denise Cush at the Bath Spa.

Dr Bowen-Reid explains: “Young women may find witchcraft attractive for a number of reasons: its identification and valuation of nature as sacred; its emphasis on empowerment through rituals and magic; its libertarian but unselfish ethic, and its positive attitude towards the body and sexuality; a personal desire to transform oneself and the world; and its support of an enchanted and supernatural worldview.”

The witch is still one of the very few images of independent female power which traditional society has given to us

“Despite all its older negative associations, the witch is still one of the very few images of independent female power which traditional society has given to us,” argues Professor Hutton.

Speaking about her first experiences of what she believed was the supernatural years later, Valiente recalled: “Just for a moment I had experienced what was beyond the physical. It was beautiful, wonderful. It wasn't frightening. That, I think, shaped my life a lot.”

But despite pioneering one of the world’s most popular religions, Valiente liked to keep things simple in her practice.

“Doreen was firmly on the side of natural magic rather than elaborate rituals,” says Heselton.

“She preferred to go up onto the Downs above her home in Brighton under a full moon, on her own or with a few companions, perhaps lighting a small fire in a hollow to commune with the Old Gods of the land.”

And when the exhibition closes as the autumn leaves fall, and highstreet stores find another “edgy” trend to latch onto, a blue heritage plaque placed on the orange-brick of her high-rise council flat in Brighton will alert passers-by: “Doreen Valiente poet, author and mother of modern witchcraft lived here.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks