Cannes: The decline of the world’s leading film festival

Crass commercial junket or the world's greatest movie showcase? Next week's Cannes festival is both, says Geoffrey Macnab – but commerce will triumph over art

Flash back to Cannes 1996. The party for Danny Boyle's Trainspotting provides an excuse for hedonism on a scale excessive even by festival standards. In one hall, Leftfield are playing to a celebrity audience including Leonardo DiCaprio, Mick Jagger and Damon Albarn.

The noise is deafening. Outside, by the pool, footage of Sean Connery as James Bond is on permanent loop on a big screen as partygoers begin to behave ever more rowdily. In the corridors, there is the sound of football chants. Inside, an elderly, well-dressed man with a silver beard is wandering forlornly on his own through the party, looking as if he is lost in Hades. The man is Robert Altman, one of America's most distinguished film-makers but unrecognised here. The magician David Blaine smashes the watch belonging to Working Title boss Tim Bevan as a party trick. The morning after the party, Trainspotting author Irvine Welsh and Oasis's Noel Gallagher are found at the Hotel de Cap swimming pool in loungers at 7am.

"It all went on. It just built the legend of the film," recalls Trainspotting producer Andrew Macdonald. "We knew we had something pretty good because it [Trainspotting] had been a success in the UK, and what we tried to do was flaunt that and create as much of a stir as possible. PolyGram had this private jet. We used it almost like a bus. We invited our own people and got them flown up and down."

Take another image, from late on the first evening of the 2006 festival. The press screening of the opening film, The Da Vinci Code, has just finished and the world's critics are stampeding out of the Palais Du Cinema to file their (largely negative) reviews in time for the next day's papers. Their hostility counts for absolutely nothing; Cannes has effectively been taken over by the Da Vinci marketing team to generate maximum exposure. The next day, the Da Vinci Code cast and crew arrive in town. Amid all the hoopla, the Cannes reviews are immediately forgotten.

These snapshots sum up perfectly what can make Cannes so vexing. It is a festival that sometimes appears to be suffering severe personality disorder, uncertain whether it exists to celebrate art or commerce. When the two worlds collide, confusion often ensues. Parties and photo opportunities risk distracting attention from the once-important fact that there are films to be shown.

The 61st festival begins next week with a screening of Fernando Meirelles's Blindness, an adaptation of the Nobel Prize-winning author José Saramago's novel about a city in which 90 per cent of the population goes blind. It is a storyline that seems highly appropriate for Cannes. Festivalgoers may not lose their eyesight, but many risk losing their sense of perspective over the festival fortnight.

In the hyper-charged atmosphere of Cannes, judgement can become erratic. Critics will praise as masterpieces films that appear nothing special when seen a few months later in the cold light of a London screening room. Distributors may pay fortunes to acquire titles that it turns out no one wants to see. Festival programmers will overlook gems (for example, the Oscar winner The Lives of Others was rejected by Cannes). Juries will ignore what later come to be regarded as the finest films (the Coen Brothers' No Country for Old Men was given nothing at last year's festival).

While the official festival showcases cinema as art, the Cannes market (set up in 1961) is an old-fashioned bazaar in which everything is for sale – arthouse, porn, horror pictures, documentaries, action movies, even auditorium seating. The two events feed off one another. The festival confers a little class on the market; the market, in turn, provides the bustle and vulgarity that gives the festival its colour. That, at least, is the theory, but sometimes, amid the relentless photo opportunities, publicity stunts, junkets and trade announcements, the "art" gets swamped.

"Cannes is two very distinct things. It is the film festival, which I think is of marginal importance," suggests Ealing boss Barnaby Thompson, producer of St Trinian's, of the art/commerce dichotomy. "In the 1960s and 1970s, it [the festival] absolutely represented international cinema, but now there are these two parallel worlds – arthouse cinema, and commercial, mainstream cinema." It is no secret which world is in the ascendant.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Most years, one Hollywood tentpole movie will descend on Cannes, whether it's The Da Vinci Code or Star Wars. This year, it is the turn of Steven Spielberg's Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. Cannes, for a day or so, will turn into a monster junket for that film. This is the Faustian bargain Cannes strikes with the Hollywood studios. The attention it receives as a consequence of playing host to such a film is immense, but the downside is that the competition films risk being eclipsed. Arthouse movies such as the Dardenne brothers' Rosetta or Abbas Kiarostami's The Taste of the Cherry may win the festival's main prize, the Palme d'Or, but the world's media will so fixated on the stars that their success will hardly be noted. "I don't think a sticker saying 'Palme d'Or winner' means anything in Britain," suggests Macdonald.

"Whores everywhere," one of the characters in Irwin Shaw's novel Evening In Byzantium says of the festival. "In the audience, on the screen, on the streets, in the jury room... this is the living and eternal capital of whoredom for two weeks every year. Spread your legs and take your money. That ought to be printed on every letterhead, under the seal of the city of Cannes."

Such an assessment may tally with outsiders' view of Cannes as being exclusively about starlets, red carpet premieres, moguls with cigars holding court on the Carlton Terrace, sex and money. It is part of the self-generated myth of the festival, but talk to the delegates who attend and they present a far more prosaic view of their fortnight on the Riviera.

Director Mary McGuckian will be in Cannes next week for a private screening of her new film Inconceivable, starring Jennifer Tilly, Andie MacDowell and Geraldine Chaplin. A comedy drama about infertility, it has the tag line, "10 babies, nine mothers and one V C father." It's about singles, lesbians, infertile couples, a pair of gay men, "all desperate for the one thing that will change their lives forever – a child."

McGuckian gives the notion that Cannes is losing its importance short shrift. "Cannes matters to me," she says. "And it's not glamorous, either." The festival, she points out, isn't just somewhere to show films; it's also a place to get them financed. "Almost every film I've made has involved a good week in Cannes, schlepping up and down the Croisette [the seafront thoroughfare]. We all have the blisters to prove it."

Her next project, a satire on Hollywood celebrity called The Making of Plus One, will be partly shot in Cannes. It will explore the tensions between art and commerce in the independent-film world. "In Cannes, that is very exemplified. On the one hand, you have the red carpet and the A-list cast who are attracted to the publicity circuit set up around them. Cannes is definitely a promotional gig. On the other side, you have real film-makers and people in the business – thousands of them."

If the festival really was a whores' convention, it is highly doubtful that Steven Soderbergh would have chosen Cannes to launch his two-film magnum opus about Che Guevara, The Argentine and Guerrilla. The films are to screen as a single, four-hour project "so as not to pit Soderbergh against himself," in the words of the Cannes general manager, Thierry Frémaux. In spite of all the Cannes hoopla, the work will be taken seriously.

British film-makers who've been neglected at home have often received an all-important boost in Cannes. Mike Leigh, with Naked and Secrets and Lies, and Ken Loach, with Hidden Agenda and The Wind That Shakes the Barley, among other films, are examples of directors who've been feted in Cannes. In the wake of their success, British financiers and audiences have begun to cherish them more, too. Many are hoping that Terence Davies, whose new film Of Time and the City screens in official selection, and who has long been revered by the Cannes selectors, will receive a similar boost this year.

It is dismaying how easily (if expensively) publicity can be bought in Cannes, yet it remains the festival where young directors most crave their work to be included. The programmers are prepared to take risks on new talent – witness, for example, the decision to include Andrea Arnold's Red Road in competition two years ago, or to make Steve McQueen's debut feature Hunger, about the IRA hunger-striker Bobby Sands, the opening film in the Un Certain Regard sidebar this year.

"It is still the No 1 one festival for us," suggests Robert Beeson of the UK distributor New Wave Films, which has already pre-bought several of this year's festival titles, among them Le Silence de Lorna by double Palme d'Or winners the Dardenne brothers, and the Turkish auteur Nuri Bilge Ceylan's Three Monkeys. However, Beeson's account of a typical festival for him won't chime at all with most outsiders' preconceptions. For him, Cannes is simply about watching and acquiring movies. "We're seeing the films we want to see, buying one or two and that's it. You can ignore all the rest – except when you can't walk down the street," he says of the circus-like atmosphere of the festival.

Cannes is the clearing shop of world film. Distributors like Beeson will be watching five or six films a day, reading scripts – and squeezing in meetings with sales agents in their spare moments. The sales agents, meanwhile, will be sitting at their stands or in their Cannes apartments and hotel suites, relentlessly flogging their wares. It costs them a fortune to be there, but fear drives them to attend. "Who's coming this year?" a character asks in a cartoon on this year's Cannes market website. "Everyone! Who would dare not to?"

The lawyers are in town. So are the studio executives and one or two studio bosses. You can find the bankers and financiers in their yachts. The agents are in attendance. The politicians turn up for photo opportunities. (Macdonald recalls meeting the then Tory Secretary of State For National Heritage, Virginia Bottomley, in 1996; she turned out to be a Trainspotting fan.) The L'Oréal and Victoria's Secret models are on permanent display, either on the billboards or in person.

Barnaby Thompson describes Cannes as "a glamorous trade fair". His festival consists of meetings every half hour – all day, every day. Macdonald, who will be in Cannes holding discussions about his forthcoming big-screen version of The Sweeney, describes the festival as "like a work conference – an important meeting-point between North America and Europe. It is very difficult to put a film together [in Cannes], but it is very possible to meet a lot of people you wouldn't normally have the chance to meet together in a short time." He concedes that there will be "a lot of young British producers getting drunk," but adds: "I think that happens in the insurance business, too."

Yes, there are parties, but these – the professionals insist – are networking opportunities, not events actually to be enjoyed. There is very little spontaneity about them. Huge amounts of thought and contrivance are behind even the most seemingly carnivalesque and anarchic events like the Trainspotting party.

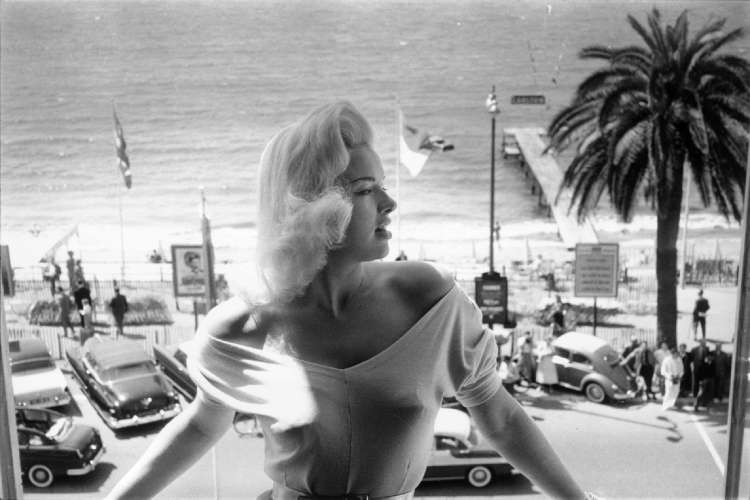

The Brits become especially agitated in Cannes, lobbying desperately for invitations to events (for example, those held by BBC Films or Film4) at which they might meet potential financiers. And when a starlet removes her bikini top, as most famously happened when Simone Sylva accosted Robert Mitchum on the beach in 1954, you can rest assured that the photographers will have been tipped off in advance.

"It [Cannes] is a hard place to get things done. It's a hard place to get a drink because it's busy and expensive," Macdonald says. "It's hard to see films because the bureaucracy is so difficult. I don't think most people in the business would choose Cannes as their favourite thing to do."

What Cannes does provide is (in Thompson's words) "the oxygen of publicity". Last year, by bringing actresses in gymslips as well as actors such as Rupert Everett and Colin Firth to Cannes, Ealing was able to introduce the foreign press and distributors to St Trinian's. "The challenge was to make a noise so that every distributor who came to the Cannes festival was aware of what St Trinian's is."

There is a strange mismatch between the image of the festival as described by the professionals attending the market and the Cannes of popular myth. The former make the event sound downbeat and even a little dull. It's as if it's a matter of obligation for them to spend several days on the Riviera but they'd much rather still be at home. In their accounts, the world of Brigitte Bardot and Roger Vadim, topless starlets, Truffaut, Godard, politics, rebellion and high living seems very far away. As they describe the daily rigmarole of meetings and conferences, they manage to make the world's most glamorous film festival sound like a ball-bearings convention in the West Midlands.

Just occasionally, though, you suspect they are protesting too much. They'd be quick to complain if they weren't able to attend or if they couldn't get invitations to the parties. It is in their interest, too, to present a downbeat account of the festival just in case the folk back home think they're having too much fun.

"The best thing about it is still watching films," says Macdonald, stating something that seems self-evident about Cannes but which comes close to being forgotten among all the other distractions.

The 2008 Cannes Film Festival runs from 14 to 25 May ( www.festival-cannes.fr)

The top five this year

The Argentine /Guerrilla

It's two in one from Steven Soderbergh with his double feature biopic of Che Guevara starring Benicio Del Toro. At four hours long it could be heavy going, but advance word suggests a film on the scale of The Godfather or Apocalypse Now.

Changeling

Clint Eastwood is Mr Reliable. Like Howard Hawks or John Ford, he rarely makes a bad film. His latest, with Angelina Jolie, revolves around the kidnapping of a child.

The Headless Woman

Lucrecia Martel is one of the most original and idiosyncratic young film-makers working today. After The Swamp and The Holy Girl comes her third feature, a drama which – judging by its title – promises to be just as disorienting as its two predecessors.

Maradona

Emir Kusturica's documentary about the portly football wizard who once scored a goal against England with a little help from his hand.

Linha De Passe

The Latin-Americans are invading Cannes this year and hopes are high for this football-themed drama from Brazilian master Walter Salles and Daniela Thomas.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments