Cut! Celluloid's last hurrah

The Master was shot on celluloid, but with manufacturers in crisis, and most cinemas screening digitally, it's one of a dying breed. Geoffrey Macnab asks the experts if it will be missed

This summer, at around the time the Olympics were taking place in London, a movie crew was in town, orchestrating a merry chaos of car chases and chases for The Fast and the Furious 6.

They were burning through film as they did so, shooting on Kodak stock. Meanwhile, over in France, Nicole Kidman was starring as Princess Grace, and looking as glamorous as any star from the golden era, in a new biopic Grace of Monaco, which was likewise being shot on film. Tom Hooper's Les Misérables, his eagerly awaited follow-up to The King's Speech, was nearing completion and was also being made on film. Current indie hit The Beasts of the Southern Wild was shot on Kodak Super 16. The Artist and The Tree of Life likewise originated on film.

All of this activity belies the fact that the endgame is underway. Without audiences noticing, 117 years after the Lumière brothers held their first screenings at a cafe in Paris in 1895, film is disappearing – and The Fast and the Furious 6 and Grace of Monaco aren't going to save it.

Directors like Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg and Quentin Tarantino speak in sacral terms about celluloid: its texture, its smell, its organic quality. “I will remain loyal to this analogue artform until the last lab closes,” Spielberg declared. Well, it looks as if the last labs may be closing rather sooner than he expects. In the US, Kodak is in Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection as it tries to reinvent itself as a new company for the digital era. Last month, Fujifilm announced it would stop making film for movies. Earlier this year, 20th Century Fox became the first Hollywood studio to confirm that it would release its movies in a “digital format”. The others are expected soon to follow suit.

In British cinemas, it is a similar story. “Regardless of my affection for film, I wouldn't see it as being something of the future,” says Ross Fitzsimons, director at leading UK independent distributor/exhibitor Curzon Artificial Eye. “We have film in nine of our 12 screens... but around 95 per cent of what we screen is digital.” Clare Binns, Director of Programming and Acquisitions at City Screen Picturehouse Cinemas, estimates that only two per cent of City Screen screenings are on film.

Eighty-eight per cent of UK cinemas are now digitised. “Put it this way, four years ago, the amount of feature film being processed for film prints round the world stood at about 13 billion feet, which is about 1.2 million miles,” notes David Hancock, Senior Principal Analyst at Screen Digest. “That's the equivalent of (flying to) the Moon five times and back. This year, we are probably down to 3.5 billion.”

The less demand there is for film stock, the less will be made – and the more expensive it will become. It's not just digital technology that is to blame. Another factor helping squeeze the life out of film is the price of silver, one of the ingredients needed for making and processing film stock. “For about 20 years, it [silver] stood at $5 an ounce and it peaked two years ago at $50 an ounce. It's now about $28 to $30 an ounce,” says Hancock.

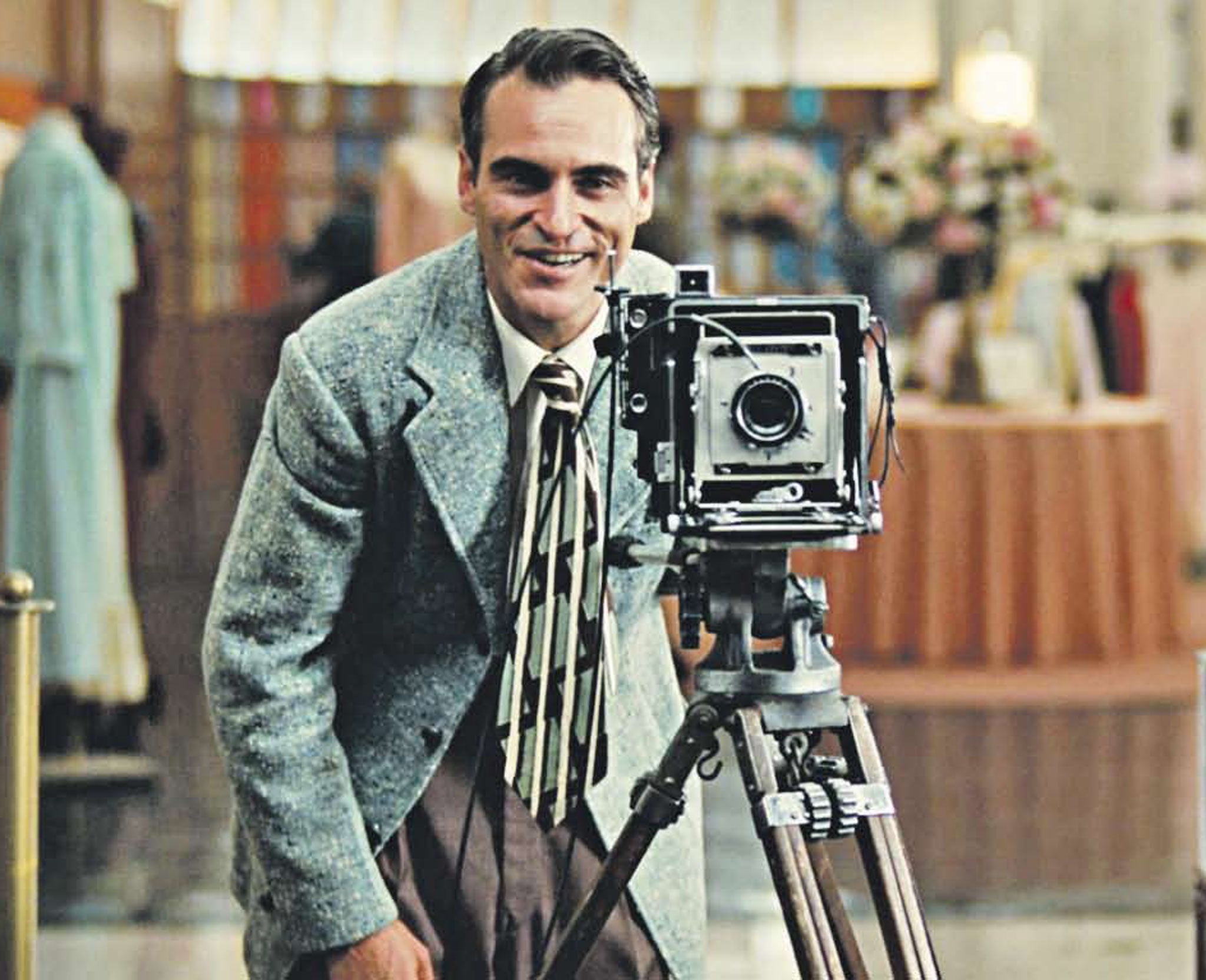

Even when directors do shoot their movies on old fashioned celluloid, there is now no guarantee they will find cinemas that can show them. In a quixotic (and arguably self-defeating) act of defiance, Paul Thomas Anderson made his new movie The Master on 70mm. His distributors around the world are discovering there are fewer and fewer cinemas equipped to show the film in that format. In Britain, the film is being seen digitally almost everywhere. The distributors released a single 70mm print which could be seen first at the Odeon West End before going on a tour of some regional venues.

We are shortly to see Lawrence of Arabia, one of the greatest widescreen movie epics of all, back on the screens. It won't be on 70mm film, though. This is a 4K digital restoration. Some argue that director David Lean is being betrayed by having his movie digitised. After all, he shot it on film. Then again, the fetishisation of film can be taken to extremes. The great Finnish director Aki Kaurismaki insists that every movie shown at his Midnight Sun Festival deep in Finnish Lapland should be projected on 35mm. At a John Boorman retrospective, the audience sat in a cinema watching a print of Point Blank that was scratched, very murky and had strident Finnish subtitles. You could hardly think of a worse way in which to watch Boorman's classic. As the director told us at the end, we hadn't quite seen the film he had made.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Binns, a former projectionist, says that she prefers film to digital... just as long as you're watching a pristine print – and her point is that you almost certainly never are. “I like to see 35mm but I like to see a 35mm in good nick. Actually, after six weeks, most 35mm prints are not.” Cinematographers now seem to acknowledge reluctantly that the film game is up. “Definitely, celluloid still offers subtleties that digital can't. It's probably the imperfections of what film gives that makes it so beautiful,” says Tat Radcliffe, a director of photography whose credits include the BBC TV serial Casanova (shot on 16mm film), the award-winning Italian film La Doppia Ora (35mm) and the new romantic comedy horror Love Bite (shot digitally.) “It's very sad and it's controversial. There's a craft [to shooting on film]. A lot of cameramen had immense power when they talked over their work at laboratory time. That has been taken away from them – this black art that nobody really understood other than the cameramen and the laboratories.” Now, Radcliffe laments, any executive can wander into the labs and alter the quality of the image “at the touch of a button”.

The reality is that film is vanishing. The question is whether or not this should be a cause for regret. “I have come to terms with the fact that there is an inevitability that if I go to the cinema as a customer, I am most likely to see digital projection,” Charles Fairall, Head of Conservation at the BFI National Archive, says. “I still want to go to the cinema! I'd far rather go to the cinema than watch... at home on TV.”

Binns makes a similar point. Film is dying, cinema isn't. “Digital has opened up the possibility of far more people seeing film,” she says. “Looking back will get us absolutely nowhere.”

'The Master' is out now; the 4K restoration of 'Lawrence of Arabia' is in cinemas from 23 November

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies