Dazzling spectacles: How arthouse film-makers are helping to rid 3D of its gimmicky image

As a host of enticing movies get set for release, James Mottram welcomes cinema's vivid new dawn

Last November, at the Los Angeles Blu-Con, an event designed to highlight innovations in Blu-ray entertainment, director James Cameron took to the stage. He was banging the drum for the Blu-ray launch of Avatar, already the biggest-grossing cinematic release of all time – thanks in part to its stunning use of 3D technology. Then came a question from the audience: is 3D just a Hollywood fad? "We're way past that," he snorted. "It's almost a waste of time to even answer that. It is here and it's here to stay... this is a renaissance and it's going to continue indefinitely."

With three of 2010's top five movies – Toy Story 3, Alice in Wonderland and Shrek Forever After – shot in 3D, the renaissance is indeed in full swing. Yet even Cameron probably couldn't have envisaged who would be taking up the baton next. From documentaries by European auteurs like Wim Wenders and Werner Herzog, to the feature-length films of everything from classical opera to the Isle of Man's world-famous TT motorcycle race, it seems the stereoscopic craze is no longer confined to the Hollywood blockbuster or computer-animated cartoons. The age of 3D arthouse has finally dawned.

The first of these to reach cinema screens in the UK is Carmen in 3D, courtesy of Francesca Zambello's production of Bizet's opera at the Royal Opera House last summer. Shot over two sessions, with cast members Christine Rice and Bryan Hymel playing Carmen and Don José, the film is directed by Julian Napier, who as far back as 2003 was shooting 3D race sequences for a touring production of Andrew Lloyd Webber's Starlight Express. Evidently the next logical step, after years of relaying HD-quality productions to local cinemas, it offers the illusion of sitting in the best seat in the house – without the extortionate ticket price.

The same can be said for the forthcoming Lord of the Dance 3D, which finally brings Michael Flatley's Irish dance spectacular to the big screen. After years of batting away propositions to put the show on screen, creator/star Flatley relented when he realised it could be filmed in 3D. "I couldn't have done this five years ago," he told me. "It shows the whole project from a different dimension. It gives a different texture and feel to the show. I think it lets the viewer in some place they wouldn't normally get access to."

With the film version a blend of shows from Dublin, London and Berlin, director Marcus Viner puts the camera in and around Flatley and his dancers – to the point where, at times, it feels like being sucked inside the troupe. Flatley, though, thinks the use of 3D is "understated", believing it's not there as a gimmick – a frequent complaint of the medium that goes back to the 1950s when it was first used to enhance B movies. "There's no shock-value stuff in there. I don't think you'll get any cheap shots in this one. It's completely different. I think the experience is intensified with the 3D."

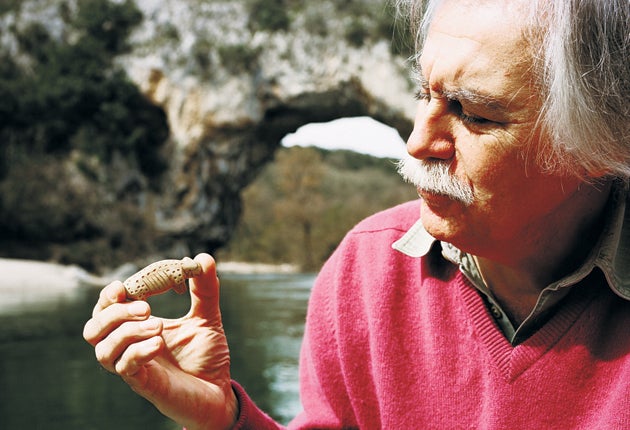

Still, be it opera or dance, there will always be limitations in bringing a show that's been primarily designed for a stage to the screen. Arguably, the most innovative use of 3D to date has been in the unlikeliest of places. Werner Herzog's Cave of Forgotten Dreams takes the audience into the Chauvet caves in the South of France, which boast some of the earliest known cave paintings, dating back some 30,000 years. First discovered in 1994, the caves are inaccessible to tourists, for fear of damage to the surroundings. Even those admitted can only use a narrow walkway, rather than tread on the fragile ground.

Under such strict conditions, Herzog's mission was to get viewers up close and personal to the paintings – a task 3D was made for. "We are doing something nobody has done with 3D," he states, without hyperbole. Indeed, as the camera glides over the intricate drawings – showing at least 13 different species of animals, including horses, cattle, lions and bears – you're tempted to reach out and touch them. For Herzog, 3D offered the chance to replicate the canvas, as much as the paintings themselves. With the images etched onto any surface – not just flat walls but "niches, bulges and protrusions" – bringing them into the third dimension underlines "the real drama" of the paintings, he says.

As obvious as it sounds, while a 3D movie offers a unique stab at creating spatial awareness and depth of field, film-makers are only just getting to grips with this. It's certainly why 3D conversions – as seen with Clash of the Titans and The Last Airbender – have left much to be desired. With neither film actually shot in 3D, and only hurriedly converted in the editing suite later on, the end results were little more than the effect delivered by skimming through crude pop-up books. But then take a film like Wim Wenders's Pina, his new documentary about the work of the late German choreographer Pina Bausch; his use of 3D is nothing short of spellbinding.

With Bausch's avant-garde work staged by the Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch ensemble, intercut with reminiscences about her influence and personality, rarely has a screen depiction of dance felt so real and so engrossing. "We wanted 3D to enter space and to allow us into the physicality of these dancers, and allow us into the space that for me created the effect of Pina's work and the emotion," he says. "But we didn't want it to be in itself attractive. My dream for 3D is that it would make itself invisible after a few moments... "

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Wenders first encountered the technology in 2007 when he saw U2 3D, the groundbreaking concert film that brought the Irish rock band's Vertigo tour into the third dimension. "It had all the flaws and faults you can possibly imagine. Space was there but movement was disastrous. But I just looked at it and tried to not see the faults and just tried to see what the potential of it was." As he points out, across the history of cinema, techniques from zooms to hand-held shots, have hitherto created the illusion of space. "Film has made us all believe – and we accepted it – that it had access to space. But space itself was never there. It was always fake. Only when I saw that door open did I think I have the tools to do it."

With that door open, the potential seems limitless. In late April comes the release of TT3D: Closer to the Edge, the world's first full-length 3D sports documentary, which tells of the 2010 edition of the infamous Isle of Man Tourist Trophy motorbike race. While there's plenty of human drama, with the film focusing on some of the maverick racers who annually risk life and limb on the circuit, it's the mind-bending footage of the TT that truly grips. It certainly makes Sky's 3D broadcasts of Premier League football look rudimentary.

Intriguingly, later in the year, we will see Martin Scorsese's first foray into the medium with Hugo Cabret – his adaptation of Brian Selznick's illustrated book about a Parisian orphan. Likewise, Baz Luhrmann has recently confirmed that in August he will begin shooting his adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby in 3D. With Leonardo DiCaprio and Carey Mulligan as Gatsby and Daisy Buchanan respectively, it may not be a story that immediately lends itself to such techno wizardry, but such innovation will undoubtedly bring Fitzgerald to a new audience.

Certainly Cameron will be happy. Since Avatar emerged, the director has gone on record to complain that his beloved 3D was being frittered on genre films like 2010's Piranha 3D. "That is exactly an example of what we should not be doing in 3D," he told Vanity Fair. "Because it just cheapens the medium and reminds you of the bad 3D horror films from the 1970s and 80s, like Friday the 13th 3D. When movies got to the last gasp of their financial lifespan, they did a 3D version to get the last few drops of blood out of the turnip." Given the seventh – and reputedly final – Saw film was shot and released in 3D, he has a point.

"I share James Cameron's disappointment," adds Wenders. "He said very clearly, 'I've put a high mark and now everybody is jumping under it.' And I agree. It's a little bit of a pity. It's still in the realm of fairground rides." Yet while the 3D film is beginning to escape its gimmicky image, thanks in part to Wenders's work, he sounds a note of caution. "The problem still is reception – where can you see it?" he says. "Are there going to be enough screens? Are arthouse cinemas able to open up to it?" With inflated ticket prices charged for the 3D experience, partly to compensate for the extra costs involved, it may yet be a while before it goes from novelty to norm.

'Carmen in 3D' is out now. 'Lord of the Dance 3D' opens on 13 March and 'Cave of Forgotten Dreams' on 25 March. 'Pina' is released on 22 April and 'TT3D: Closer to The Edge' on 29 April

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies