Django Unchained and the 'new sadism' in cinema

Quentin Tarantino's new film is the latest where killing is seen as comical. Geoffrey Macnab wonders why people fall about laughing at disembowelment and garroting on screen?

It's the "new sadism" in cinema - the wave of films in which violence is graphic, bloody but always underpinned by irony or gallows humour.

There is something disconcerting about sitting in a crowded cinema as an audience guffaws at the latest garroting or falls about in hysterics as someone is beheaded or has a limb lopped off.

It’s the “new sadism” in cinema – the wave of films in which violence is graphic, bloody but always underpinned by irony or gallows humour. There is something disconcerting about sitting in a crowded cinema as an audience guffaws at the latest garroting or falls about in hysterics as someone is beheaded or has a limb lopped off.

Many recent movies squeeze the comedy out of what would normally seem like horrific acts of bloodletting. Martin McDonagh’s Seven Psychopaths has barely started when we see two assassins who are planning a killing being blithely murdered by a passer-by themselves. The film features throats being cut and many characters being shot to pieces but is played for laughs.

However, the violence isn’t immediately signalled as comic. Seven Psychopaths isn’t like Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), with its self-consciously farcical scenes of the Black Knight refusing to concede in battle in spite of having had all his limbs cut off.

Ben Wheatley’s recent Grand Guignol camper-van comedy Sightseers shows two British tourists wreaking murderous havoc across the British countryside. When a rambler complains about their dog fouling a field, they bludgeon him to death. “He’s not a person, Tina, he’s a Daily Mail reader,” Chris (Steve Oram) reassures his girlfriend when she expresses some slight misgivings about killing innocent people. Tina (Alice Lowe) has form of her own, throwing a bride-to-be off a cliff after a hen night in which the woman flirts with Steve.

In Quentin Tarantino’s films, the violence, torture and bloodletting sit side by side with wisecracking dialogue and moments of slapstick. His latest, Django Unchained, features whippings, brutal wrestling matches and one scene in which dogs rip a slave to pieces. We know, though, that Tarantino’s tongue is in his cheek. Scenes that would be very hard to stomach in a conventional drama are lapped up by spectators who know all about the director’s love of genre and delight in pastiching old spaghetti Westerns.

A certain sadism has always defined crime movies. Whether it was Lee Marvin scalding Gloria Grahame with the coffee in The Big Heat (1953) or James Cagney’s Cody blithely shooting innocent train drivers in White Heat (1949), audiences watched the antics of gangsters with appalled fascination. From Edwin S Porter’s The Great Train Robbery (1903) to Sam Peckinpah’s blistering, slow-motion shoot-outs in The Wild Bunch (1969), film-makers have always looked to violence for dramatic effect. Well-choreographed shoot-outs and fist fights will always be intensely cinematic.

Sadism and slapstick likewise go hand in hand. Whether silent comedians slapping and hitting one another, pulling one another’s ears and twisting noses or Farrelly brothers films with their grotesque set-pieces, comedy movies have always traded in humiliation.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Nor is there anything new in making very dry comedy out of violence and death. Robert Hamer’s Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949) is a supremely elegant and witty film about a serial killer who murders off his own family members just as quickly as Chris and Tina dispose of National Trust-loving tourists in Sightseers. Frank Capra’s Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) features very charming old ladies whose pet hobby is murdering lonely old men. Howard Hawks’s His Girl Friday (1940) turns the plight of a convicted murderer facing execution into the stuff of screwball farce.

What has changed now is that genre lines have become very blurred. Young directors like Edgar Wright (Shaun of the Dead, Hot Fuzz) and Wheatley draw on horror movie conventions even as they make very British comedies. Ideas that might have previously been confined to exploitation pics have spilled into the mainstream. In the era of computer games like Call of Duty and Assassin’s Creed, death isn’t taken very seriously. Film-makers with no direct experience of war beyond what they’ve seen in other movies regard staging killings as just another part of cinematic rhetoric. At the same time, state-of-the art make-up and digital effects enable violence to be shown in far greater and bloodier detail than ever before.

Tarantino turns to heavy political and historical topics (the Holocaust in Inglourious Basterds, slavery in Django Unchained) but tips us the wink as he does so. One problem he and others face is the literal quality of film. When a slave is being flayed or a police officer is having his ear cut off, it isn’t always possible to put inverted commas round the scene and let the audience know that this horrific moment is stylised and shouldn’t be taken too seriously.

As a counterpoint to latest films from Wheatley, Tarantino and McDonagh, it is instructive to watch Joshua Oppenheimer’s grim and startling recent documentary, The Act of Killing. Oppenheimer’s doc follows various real-life killers who murdered thousands of “communists” in Indonesia in the mid 1960s. They’ve never faced punishment for what they did and still openly brag about their part in a genocide. Oppenheimer invites them to re-create some of their grisly deeds as pastiche Hollywood movies. We see these aging hoodlums dress in drag for Vincente Minnelli-like musical scenes or coming on like bad Method actors in gangster pic spoofs or even portraying cowboys in mock spaghetti Westerns. Whatever the genre they choose, there is no escaping the bloodcurdling nature of the deeds they are celebrating.

Acts of killing define the new sadism in cinema. The challenge now for film-makers is jolting audiences who’ve already seen death portrayed so many times on screen before. When they get it right, they can create scenes of extraordinary power and beauty – and they can use humour to distance themselves from the charge that they are being exploitative.

Even so, the film-makers themselves sometimes appear just a little bashful about the enormous body counts in their work. The US premiere of Django Unchained was postponed after the Connecticut school massacre in mid December. The real-life incident in which a lone gunman killed 20 school children made it seem perverse and tasteless to celebrate Tarantino’s comic-book violence.

The Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) introduced a “code” in 1930 (not strictly enforced until 1934) partly to clamp down on gangster films felt to glamorize violence. Ever since, the debates about guns, Hollywood and violence have gone round in wearisome circles. Every time there is a real-life atrocity as in Connecticut, films are held up as being in some way to blame, generally by commentators who haven’t actually seen them. Meanwhile, cultural critics are always quick to point out that violence and art go back thousands of years before the birth of cinema.

Even so, what’s often startling about the new sadism in cinema is the disregard for the victims, who are treated as walk-on props, there to be dispensed with in the most humorous, bloody and imaginative way possible. In 1989, Danny Boyle produced (and conceived) Alan Clarke’s Elephant – a TV movie set at the height of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. This was an essay about killing. Eighteen random murders were shown. Viewers learnt nothing at all about the killers or the victims. The film-makers were reminding us how desensitised we had become to sectarian violence in Northern Ireland. A quarter of a century on, that casual detachment about death has become a staple of mainstream cinema.

‘Django Unchained’ is released on 18 January

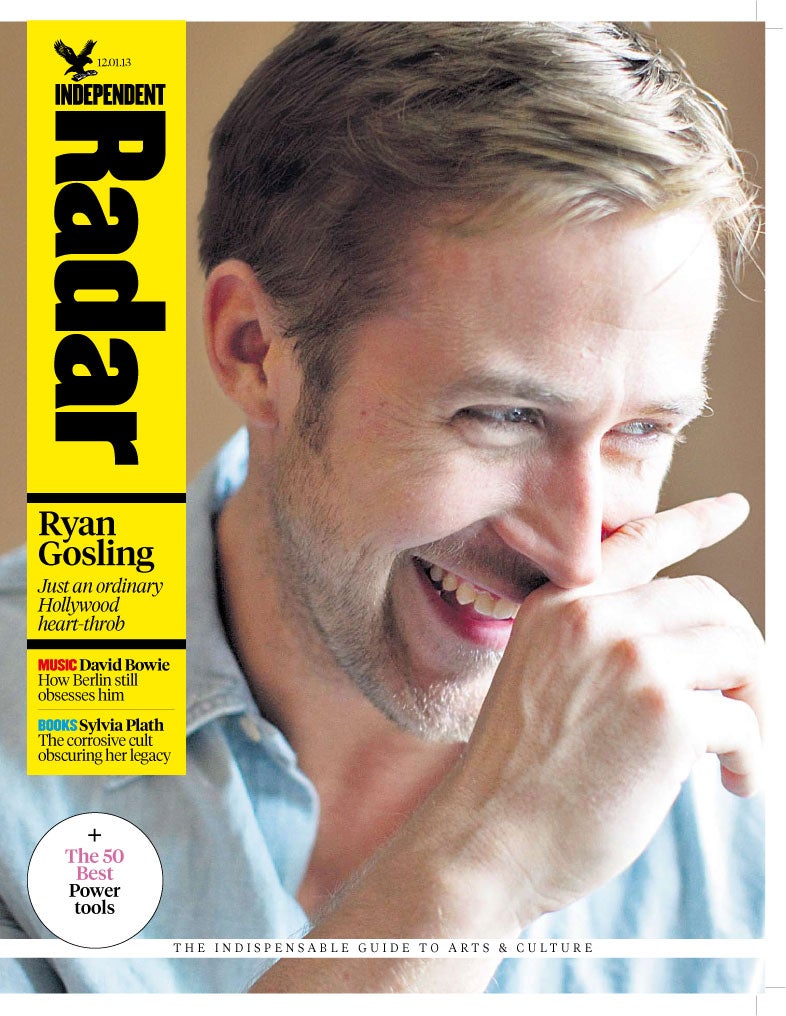

The article appears in tomorrow's print edition of Radar Magazine

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks