Dustin Hoffman interview: The Graduate talks decline of cinema, difficulties finding work and wanting to be a jazz pianist

The current state of film is 'the worst it's ever been' according to The Choir actor

It’s hard to describe seven-time Academy Award nominee Dustin Hoffman as disgruntled when he says everything in such an effusive, mild-mannered way. He looks like he’s been living the good life, with his tanned complexion and the top buttons undone on his shirt. His enthusiasm to appear in and direct films is as strong as ever, which just makes his criticisms of the film industry all the more heartfelt.

“I think right now television is the best that it’s ever been and I think that it’s the worst that film has ever been – in the 50 years that I’ve been doing it, it’s the worst,” he claims. This opinion comes despite his HBO TV show about horse racing Luck being cancelled while they were shooting the second season when PETA protested about the deaths of horses on set. He is also on the look out for a new film to direct after helming Quartet in 2012 about a group of retired musicians.

His new adventure as an actor also has a musical flavour, The Choir sees him play the musical director of an American boy choir boarding school who takes in an orphan despite his instinct that the young lad doesn’t quite have the chops to become a top class musician.

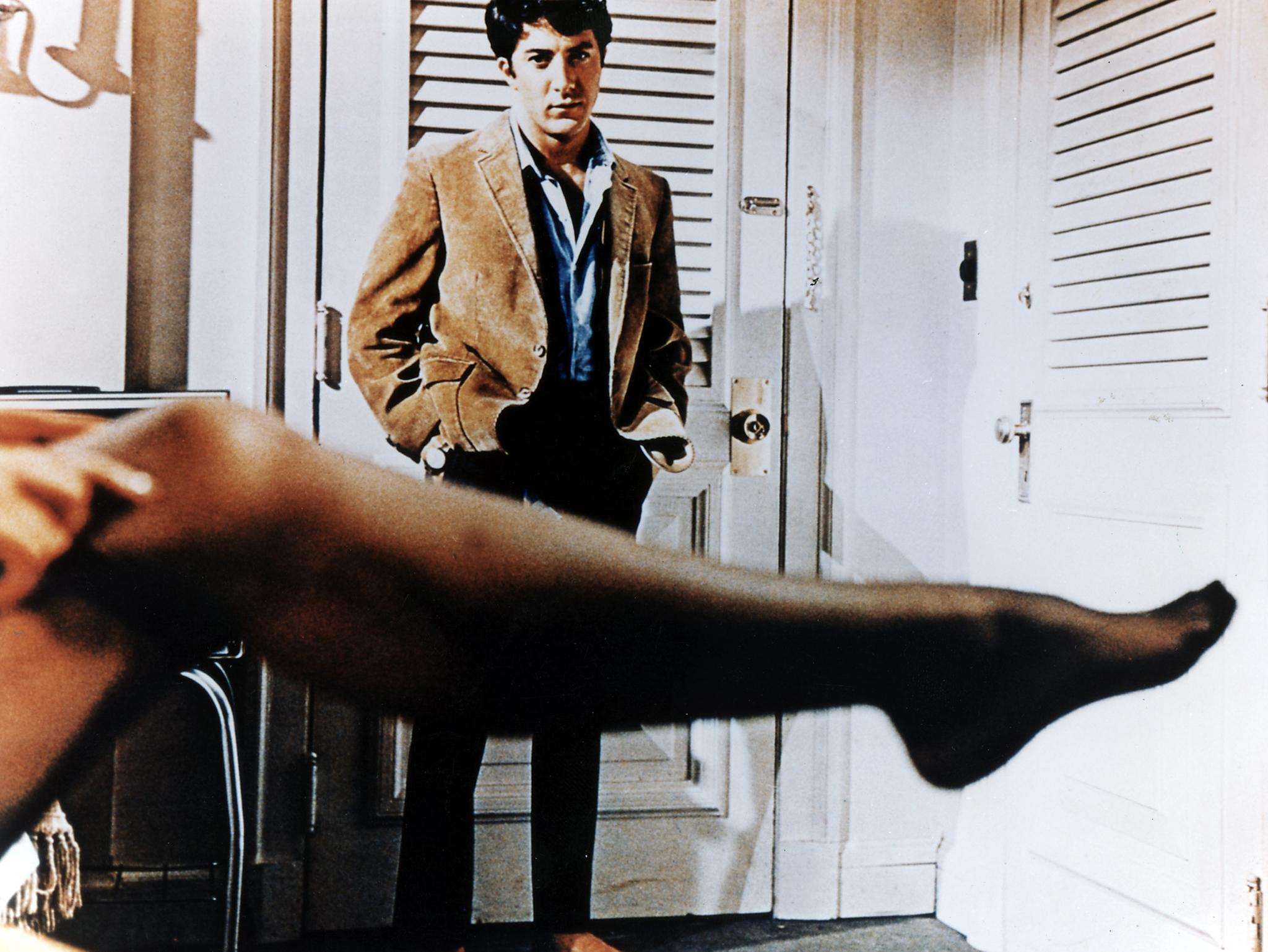

Hoffman has an ocean of experience to compare the industry of today with yesteryear. “It’s hard to believe you can do good work for the little amount of money these days. We did The Graduate and that film still sustains, it had a wonderful script that they spent three years on, and an exceptional director with an exceptional cast and crew, but it was a small movie, four walls and actors, that is all, and yet it was 100 days of shooting.”

Most films today, away from the comic strip or robot adaptations, are made in around 20 days. Part of the reason is that digital technology enables filmmakers to shoot more scenes in a day than they used to, but mostly it’s to do with the downsizing of budgets as more and more films get made. The films that have been squeezed the most by this development have been the quality dramas, a genre that has a habit of calling on Hoffman’s inimitable services.

He’s also been hit by the vagaries of time. Whereas in The Graduate, Hoffman was the one being schooled, he’s now the one dishing out lessons in The Choir. “The truth is that you come full circle. I was a freak accident, so I got a lead that happened to be The Graduate and it was like a light switch went on and I was an instant star. For most actors you start by playing euphemistically called supporting roles, it’s not even the supporting role it’s less than that, and if you are lucky you build up to supporting roles and then to starring roles – and then you reach a certain age, and unfortunately women usually reach it earlier, and you are no longer the leading man, therefore you become the supporting actor, which many times is the mentor of the lead. That is full circle.”

Yet Hoffman is also an exception to this general rule of thumb, because his name carries weight. He says of his top billing on The Choir, “It’s hard to find leading parts. In this film, if I were not a name, because they would like to draw people, this would be a supporting part. It’s really the story of the boy.”

Hoffman is being slightly self-effacing. He has a gravitas that he carries into every scene. It’s a more ruthless character than we have seen him essay for a long time. Yet like many of his great parts, Hoffman – no matter how unsavoury some of his character’s traits – manages to bring humanity to the role. In The Graduate he sleeps with both mother and daughter. Midnight Cowboy saw him play a street con man, but one who takes in someone he’s conned. In Kramer vs. Kramer, he starts out as an advertising executive who puts work before his family. His depiction of an autistic savant in Rain Man brought autism into the general public consciousness. Add to this, turns in Tootsie, Marathon Man, Lenny, Papillon and All The President’s Men, and it’s an almost unrivalled body of work.

Because of all these great roles, when Hoffman appears on screen he immediately gives his persona a sense of character. In The Choir, he gives the conductor a sense of gravitas, even before he opens his mouth. But Hoffman doesn’t see it that way. “I swear I’m not aware of that,” he says. “What I’m aware of is the longer you’re around, the harder it is to get away with murder. You’re trying to get past that so-called persona. Some actors, many stars, have a signature, and they give the audience what they want, they give them that person. I once saw John Wayne in one of his first movies and it’s not John Wayne, it’s just some guy. Suddenly, he started learning that this was the John Wayne they wanted. And he became that. I’m trying to get away from it because I don’t have a signature. I wish I did, but I don’t.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

It’s true that there is not a Hoffman aesthetic in the manner of his peers Robert De Niro or Al Pacino. He plays his characters with a gentleness, sharing performances with his peers rather than stealing scenes. When he put his superstar Hollywood reputation on the line by making his Shakespearean debut in a West End production of The Merchant of Venice in 1989, Irving Wardle of The Times noted: “Hoffman is much the most genial Shylock I’ve ever seen.” It’s a sentiment that could be applied to so many roles.

Born in Los Angeles in 1937, he came from a Jewish family, although religion was not a major part of his upbringing. Hoffman has said that he was 10 by the time he became aware of his heritage. To stop himself being ridiculed at school, he developed skills as a comedian. His father Harvey, who worked as a prop-master on film sets before becoming a furniture designer, would later admit his atheism to his son. Although by the time Mike Nichols, who had seen Hoffman in an off-Broadway play, asked him to come for his first ever screen test – to audition for the part of Benjamin Braddock, originally written as a rich WASP – Hoffman questioned whether he was too Jewish for the part.

The fact that he saw himself as an outsider is perhaps what gave him so much empathy for his conflicted characters. If Hoffman didn’t have self-doubts, they were installed in him by others, Hoffman often tells how his aunt Pearl had warned him, ‘You can’t be an actor – you’re too ugly.’ Hoffman knew that to succeed he couldn’t be pigeon-holed as being of a type, because the traditional roles for short actors with his nose were not the starring ones. His inspirational acting coach Barney Brown persuaded the talented Hoffman to move to New York in 1958 where he would be a theatre person for the rest of his life. It’s where Hoffman continues to live – although no longer on fellow actor Gene Hackman’s kitchen floor as he did when he first arrived.

The struggle to succeed shared with his peers gave him an affinity to actors. “I just like actors and I like working with them,” he says. “I have said it before that I just don’t think the public realise how much we help each other. You say to other actors ‘I just don’t think I’m doing good work,’ and the other actors say, ‘when we were just running lines you were right on the button!’ Then the director comes in and says ‘We need more energy.’ It’s like in these prison movies, you have to talk out of the side of your mouth. We help each other because we are all in the same bind.”

Hoffman has been married twice. His first bride, Anne Byrne, a 5’10” ballerina, he has argued was his trophy wife. Tall, elegant, all-American, things he perhaps wanted to be even though through the years of their marriage, from 1969-1980, he was one of the most celebrated actors in the world. They had two daughters (one a step-daughter). He has since had four children with his current wife, businesswoman Lisa Gottsegen, who he married in October 1980.

If he has one great lament, it’s that he didn’t have the talent to fulfil an ambition to become a pianist. Perhaps explaining the strong presence of music in his current work. “I love it more than anything,” he says. “But I can’t play well enough to make a living out of it. If God tapped me on the shoulder right now and said ‘no more acting, no more directing, but you can be a decent jazz pianist’... I could never read music gracefully. I don’t have a good ear. I still want to do it. I would love to do it.”

It’s this pursuit of perfection that he says keeps him going, citing Picasso touching up paintings even after they had been hung in galleries as an example of his zeal. He has a supporting role in Stephen Frears’ forthcoming The Program, which details the story of disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong’s efforts to cover up his use of performance enhancing drugs. After that? “I’m looking at everything that comes to me, I’m not getting much as far as directing is concerned. I don’t think that has anything to do with whether you are good or not, it’s just about whether your films make money or not.”

‘The Choir’ is out on 10 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments