Philip Larkin - Rhythm and rhyme

A new box set of Philip Larkin's favourite jazz focuses on the pre-war trad he adored – but the poet was no musical stick-in-the- mud. In fact, says Sholto Byrnes, he was one of our most incisive jazz critics

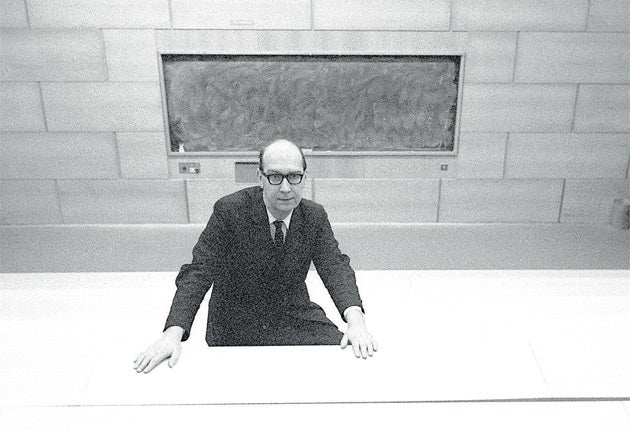

Twenty-five years after Philip Larkin's death, the reputation of the poet, librarian, and stereotype of a certain kind of fussy, repressed Englishman, has recovered from the critical rollercoaster it endured after his death. "In the early Eighties," wrote his godson Martin Amis in 1992, "the common mind imagined Larkin as a reclusive yet twinkly drudge – bald, bespectacled, bicycle-clipped, slumped in a shabby library gaslit against the dusk." By the early Nineties, however, books on Larkin's letters and his unpublished verses had transformed him into "a fuddled Scrooge and bigot, his singlet-clad form barely visible through a mephitis of alcohol, anality, and spank magazines."

This summer the anniversary is being marked by Larkin 25, a 25-week-long celebration of his life. Now the tides of indignation have passed, a warmth towards Larkin remains. So too, however, do some of the stereotypes. And Larkin's Jazz, a four-disc box set of the musicians he loved, may perpetuate them. It is quite right that the pre-war, trad jazz that Larkin wrote so well about in The Daily Telegraph from 1961-71 (a selection of which was published as All What Jazz in 1970), should make up the majority of the tracks. There is the white guitarist Eddie Condon, whose music Larkin said was "the most consistently enjoyable thing in jazz", the "bejowelled utterances" of the New Orleans clarinettist Jimmie Noone, Sidney Bechet (the subject of a Larkin poem), and above all, Louis Armstrong, whose recordings from the 1920s Larkin described as "the Complete Shakespeare of jazz".

This is consistent with the image of Larkin as a diehard traditionalist, an unrepentant "mouldy fygge", as the 1950s slang had it, for whom the birth of bebop at the end of the Second World War was not the beginning of the New Testament but a heretical development, "an irresponsible exploitation of technique in contradiction of human life as we know it," as he wrote in the introduction to All What Jazz. This was the Larkin who said he agreed with the French critic "Hughes Panassie, the venerable Frog, who matter-of-factly refused to admit that bop or any of its modernist successors was jazz at all".

He clearly liked presenting himself in this light. In 1984, when All What Jazz went into its second edition, Larkin added a new footnote. "My views haven't changed," he wrote. "If Charlie Parker seems a less filthy racket today than he did in 1950 it is only because... much filthier rackets succeeded him." Few have taken such evident pleasure in casting verbal stones against the towering figures of modern jazz, thus providing plenty of evidence for those who prefer to dismiss Larkin the jazz critic as a fuddy-duddy, a musical ignoramus straying into a field about which his judgements were worthless.

But this is far from being the whole truth, or the truth at all, inasmuch as it suggests Larkin's views were unyielding and monolithic. The secret about his relationship with modern jazz is that he was much more open-minded about, even appreciative of, the post-war masters than is acknowledged.

The startlingly positive remarks Larkin made about Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, even Ornette Coleman – the honking, squawking high priest of free jazz, a saxophonist and would-be violinist whose music is often so cacophonous that many have questioned his ability to play either instrument – are scattered among the reviews and essays. Nearly 10 years ago Richard Palmer and John White put together a new collection, Larkin's Jazz, part of the aim of which was to correct impressions about his criticism. But little of this got through. Out of the 81 numbers in the new box set, just one might be described as "modern jazz" – a recording of "How High the Moon" by the Dave Brubeck Quartet. It will, to most who buy the discs, appear an oddity. For if anything is remembered about Larkin's attitude towards Brubeck, it will be his sarcastic description of the pianist "teaching audiences to clap in 11/4 time", rather than his actual view of this particular live performance – which was that the quartet "did a splendid job".

And Brubeck was just the beginning. In 1965, Larkin wrote the following about Charlie Parker: "Technically, Parker was a genius... He developed a staggering technique, jetting flurries of notes transcribable only as sixteenths, thirty-seconds, sixty-fourths. And he was a genius musically, in the sense that... he instinctively felt his way to new harmonies, new rhythmic patterns, and showed how they could be used... He had touched off an explosion."

A few months later, he listed John Coltrane's "A Love Supreme" as one of his records of the year. Two years later, in another round-up for the Telegraph, he picked both Thelonious Monk's "Work", commending its "gay and fruitful piano", and Miles Davis's "Miles in the Sky", praising its "passages of bleak pastoralism delivered with a melancholy and kingly authority". These are not just apt descriptions – the detection of "pastoralism" in Davis's playing being a particularly sharp observation – they are also not the words of a man who cannot stand what he's listening to.

Even more extraordinary was his inclusion of Ornette Coleman's "Chappaqua Suite" in his 1967 list – "probably the most extended ramble of this philosophic freeformer, proving his consistency of conception and inventiveness without recourse to distortion." Not overly complimentary, perhaps, but generosity itself compared with how the late Benny Green, a magnificent critic and no "mouldy fygge", recorded Coleman's visit to London the previous year. "By mastering the useful trick of playing the entire chromatic scale at any given moment, he has absolved himself from the charge of continuously playing the wrong notes," wrote Green. "Like a stopped clock, Coleman is right at least twice a day."

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Who, of the two above, comes across as "fanatically Luddite"? That is the term Green's son Dominic applies to Larkin in an introduction to a collection of his father's writings – but it is the poet, not the musician and broadcaster, who sees merit in the new in this case.

It may well be that when Larkin spent an hour listening to new jazz records with a pint of gin and tonic – "the best remedy for a day's work I know" – he did not reach for the bebop of the 40s, the hard bop of the 50s, the avant garde of the 60s or the fusion extravaganzas of the 70s. That the early polyphony of King Oliver and the stride piano of Fats Waller were closer to his heart is not in doubt. But Larkin was one of our greatest jazz writers. It is important to acknowledge that the man who hailed jazz as a "new art" in 1940 could still follow and appreciate its developments long after it departed from the foot-tapping hot jazz of Armstrong et al: that he was not quite the old fogey that his detractors say he was. He may have connived in this deception himself, but Larkin's secret was that he was a better, more truthful critic than he let on. Somewhere, I suspect he is having a chuckle that the caricature of himself he invented is still fooling most of the people, most of the time.

'Larkin's Jazz' is released on Proper Records on 26 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments