When Hollywood goes to the hustings

Although they often form the backdrop to more conventional stories, elections can prove the making – or, more usually, the downfall – of big-screen characters, writes Geoffrey Macnab

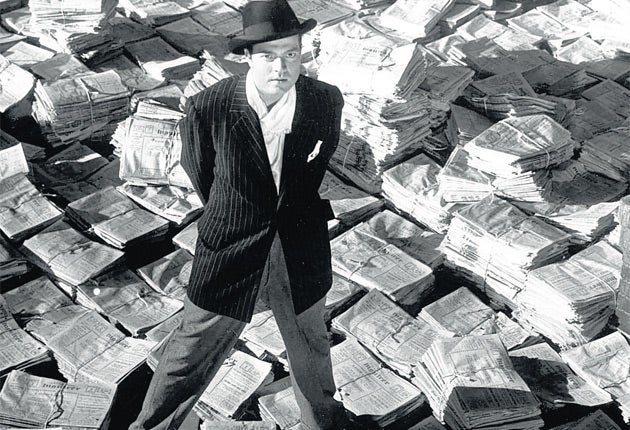

Film-makers invariably take a grim and satirical view of elections. There is a poignant episode midway through Orson Welles's Citizen Kane (1941) which reveals how quickly fortunes change for powerful and self-important men in movies who try to get themselves voted into office. The newspaper publisher Charles Foster Kane (Welles), the "liberal", the "friend of the working man", is standing for governor against the incumbent, Jim Gettys (Ray Collins.) At a huge rally, Kane

rails against the corruption of Gettys. The polls have Kane winning at a canter. Then comes the John Edwards moment.

Like Edwards (a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2008), Kane has been having an extramarital affair. The political boss Jim Gettys threatens to expose him in the media. The moment the rival newspapers publish their stories, Kane's political career is over. One day, he has been prating about morality. The next, he is a laughing stock.

Kane's humiliation at the polls is also the fate of many other movie figures. Politics on screen is a dirty business and electoral politics is squalid in the extreme. Whenever principled and honest candidates are elected to office, they're sure to become corrupted in double-quick time.

This impression is reinforced in Robert Rossen's All the King's Men (1949).At the beginning of the film, Willie Stark (Broderick Crawford) is the folksy everyman. He stands for office because he is disgusted with the graft and intimidation he sees around him. Gradually, the decent country boy turns into a boozing, power-crazed demagogue who uses tactics every bit as underhand as those he sought to replace.

A similarly grim tale is told in Fame Is the Spur (1947), a cautionary tale about a Ramsay MacDonald-like working-class Labour politician (played by Michael Redgrave) who is elected to office and seduced by the establishment. By the end of the film, he has turned into a grandee with a taste for the good life and little recollection of the injustices he originally entered Parliament to combat. Several members of Clement Attlee's government went to see the movie. As Tribune reported, they came out vowing that they would not make the same mistakes.

Elections in movies are rarely the main event. They are the backcloth against which romantic dramas or political thrillers are played out. In Hal Ashby's Shampoo (1975), the setting is Beverly Hills on the eve of the election that took Richard Nixon to the White House. The preoccupation of the film is less electoral politics than sexual politics. The film makes apparent the huge gulf between the hedonistic world inhabited by Warren Beatty's ultra-promiscuous hairdresser and the conservatism that Nixon epitomises.

One of the most memorable moments in Alfred Hitchcock's The 39 Steps (1935) comes when Richard Hannay (Robert Donat), fleeing for his life, is mistaken for a politician and drafted in to speak in a by-election. Hannay is a natural, speaking in blandishments and clichés and then launching forth into some rousing rhetoric about the plight of the common man. The longer he talks, the better chance he has of keeping his pursuers at bay. Hannay is given a standing ovation, even though he has said nothing specific about anything.

Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver (1976) also unfolds in the middle of an election campaign. Senator Charles Palantine (Leonard Harris) is running for the presidential nomination. Taxi driver Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro) volunteers to join his campaign solely so he can get close to the beautiful Betsy (Cybill Shepherd.) There is a tremendous scene in which Palantine travels in the back of Travis Bickle's cab and asks Travis what can be done to improve the country and is treated to a BNP-style tirade about New York being like "an open sewer, full of filth and scum" that the new President needs to clean up. By setting Taxi Driver in the middle of an election campaign, Scorsese and the film's screenwriter, Paul Schrader, were able to highlight the social and racial tensions that are simmering close to boiling point in mid-1970s New York.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

One of the few fictional films in which an election is foregrounded is The Candidate (1972). Bill McKay (Robert Redford) is the idealistic young lawyer who enters the Californian senatorial race in a bid to do good but is slowly corrupted. What it makes clear is the horse-trading and showmanship that is required to win any major election.

Documentaries, including Alexandre Pelosi's Journeys with George, tend to portray politicians in a far moresympathetic light than fictional films. Film-makers have tended to steer clear of elections. When they have touched on electoral politics, they've done so in an oblique way, using the battle for votes as a framing device for comedies or thrillers. If there is drama to be found, it is invariably in what is happening behind the scenes.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies