Watchmen, Zack Snyder, 160 mins, 18

This successful transition from revered comic novel to fantasy movie means nothing is now unfilmable

The word "unfilmable", as applied to fiction, used to mean something – until the advent of computer imagery, and suddenly anything that could be imagined, described or drawn could be turned into the stuff of celluloid. But there's one revered fantasy work that still merits the epithet, and that's the 1980s comic strip Watchmen.

The story's wilder visual elements – not least a size-changing, levitating, blue-skinned Übermensch who builds a glass fortress on Mars – are no longer a problem. What still makes Alan Moore's and Dave Gibbons's creation so intractable is the density of their multi-stranded, philosophically provocative satire, originally published in 12 more or less self-contained episodes in 1986-87. If any drawn narrative deserved the tag "graphic novel", it was this – a positively Dostoevskian meta-comic about, among other things, the moral and ideological murkiness of the superhero myth.

The film-maker to finally scale this freakish mountain is Zack Snyder. Responsible for the swords-and-sandal epic 300, he might seem too heavy-metal a sensibility for Watchmen's sophistication. But he's done an intelligent, painstaking, often mightily imposing job in corralling the comic's narrative sprawl. Whether much of the dizzying tangle will make sense to non-initiates is another question.

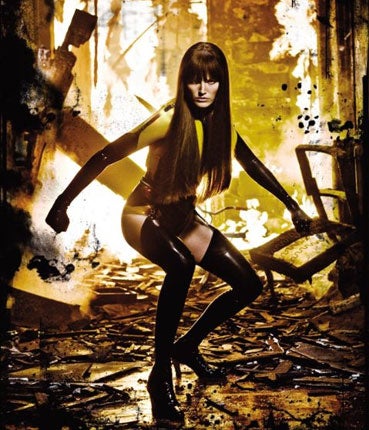

Here's the gist: we're in a parallel version of the 1980s, with Nixon still in office and the Cold War still raging. The story begins with masked vigilante Rorschach – a Travis Bickle-style sociopath simmering with vengeful misanthropy – investigating the murder of old cohort The Comedian (Jeffrey Dean Morgan), a government-endorsed reactionary goon, depicted as a cross between Rambo and Marvel's Nick Fury. The narrative takes in two generations of costumed crime-fighters, including hooded technophile Nite Owl (Patrick Wilson), now a paunchy Bruce Wayne-ish loner brooding in his bachelor den; vampy Silk Spectre (weak link Malin Akerman, woodenly sexy); and Dr Manhattan (Billy Crudup), a scientist transformed by nuclear exposure into a quasi-divine blue-glowing apparition.

Bold as Snyder is, you can't help questioning the publicity claim that he's "visionary". The visionaries here remain Watchmen's creators, writer Moore (who, as usual, declines to have his name in the credits) and artist Gibbons. Snyder's adherence to their original – up to a point – is so faithful as to be, if not slavish, certainly fetishistic. He not only crams in most of the narrative, but essentially reproduces Gibbons's drawings in three dimensions, beginning with the famous, already cinematic opening sequence – a mock zoom out from a close-up of a blood-spattered smiley badge.

There's little in the film that isn't in the comic: the most original addition is a clever credit sequence, condensing the back story into a series of tableaux vivants taking us from the 1940s to the 1980s, via Dealey Plaza and Apollo 11. Snyder also, characteristically, raises the ante on the book's already formidable brutality.

But the truly bold move by writers David Hayter and Alex Tse is to retain the complex structure of the original strip, the film falling into a series of episodes, each with its own narrative style. It's quite something to capture the poetic, poignant tone of the sequence in which Dr Manhattan retreats to Mars to ponder his destiny, a succession of moments jumbled into a jigsaw of quasi-simultaneous event. Also daring is the macabre flashback in which Rorschach reveals to a therapist why he's so twisted: strong stuff, showing up the supposedly adult grimness of The Dark Knight for the posturing solemnity it is. Jackie Earle Haley – one of the cast's several more-or-less unknowns – is an extraordinary, creepily affecting Rorschach, even more chilling unmasked as a weaselly runt than when wearing his inscrutable ink-blot face.

The other revelation is Billy Crudup, unrecognisable as Dr Manhattan, the film's most magnificent visual creation. There may be very little of the actual Crudup visible on screen (those glowing copper-sulphate pecs surely aren't his), but, via Manhattan's blank visage, he makes this hugely improbable figure a touching and tragic enigma – Shiva the destroyer with Buddha's smile and residual traces of boffin gaucheness.

In his omnipotence, Dr Manhattan is to the traditional superhero what CGI is to pen and ink. But there's the problem. When Dave Gibbons drew Manhattan's Martian retreat, a glass Alhambra rising out of pink sands, the effect was a gracefully bizarre miracle: on screen, it's another mechanical-looking digital effect. The more the film drifts towards blockbuster spectacle, the more banal it is: by the end, it might as well be a below-par X-Men episode.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

But for all its flaws, Watchmen attempts a scope that most movies, of any genre, wouldn't consider (and wouldn't have to), running from intimate bedroom drama to cosmic catastrophe. Watchmen isn't a great film, and I suspect it will be quickly forgotten, while the flawless original gets richer with time. Yet, if you have any interest in comic-strip cinema, you'll find something here to take your breath away.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments