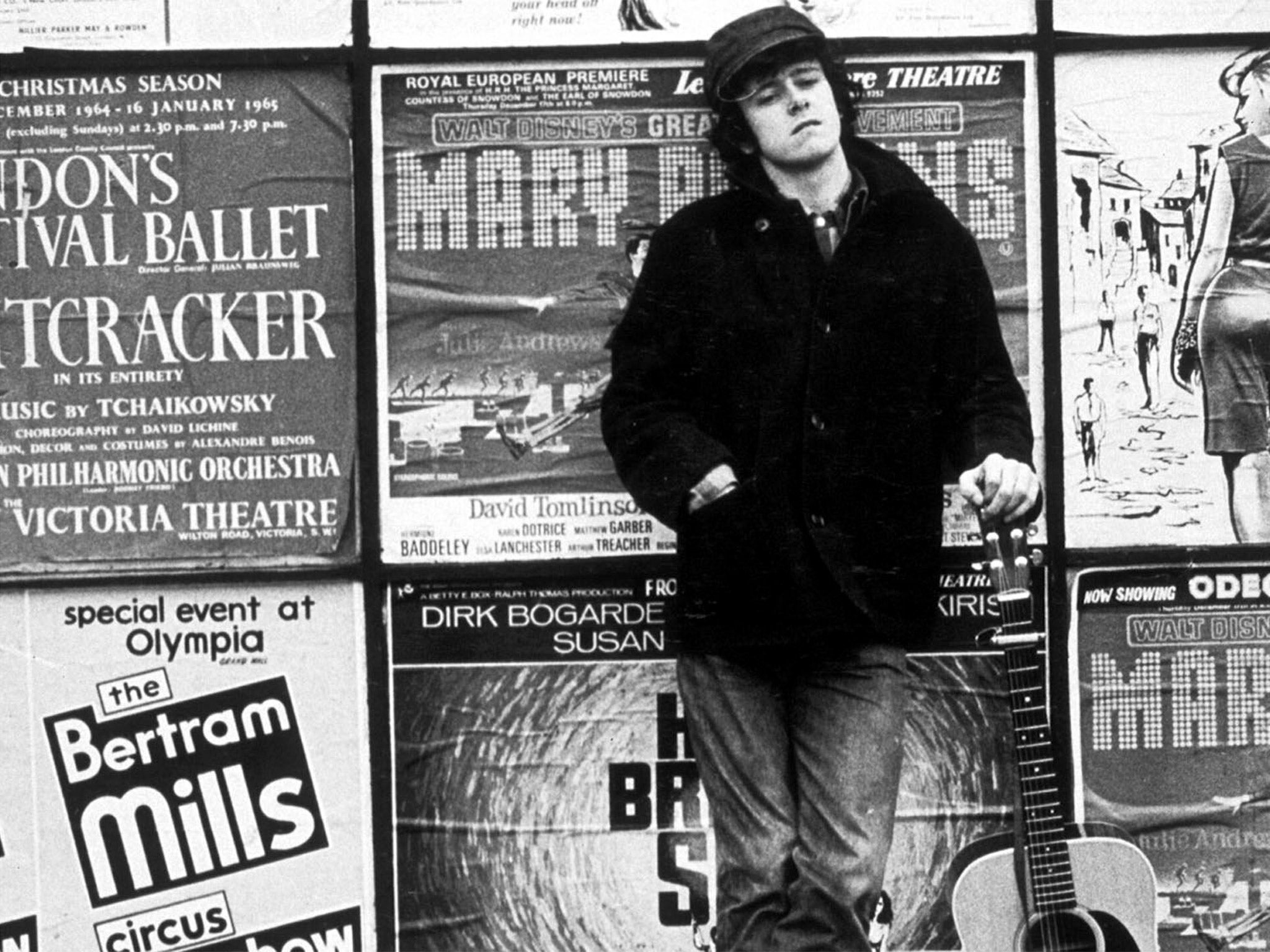

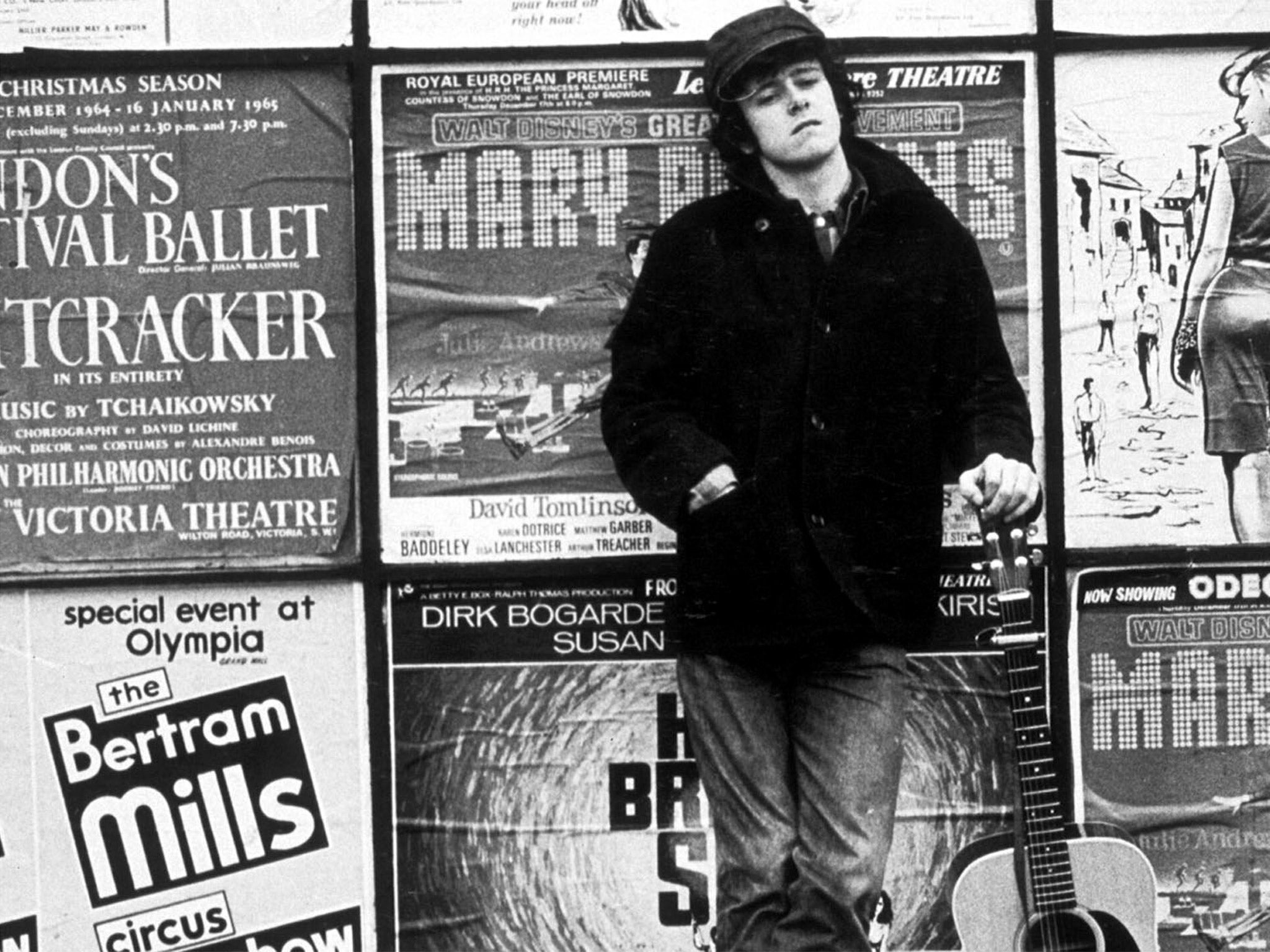

Donovan interview: The singer is releasing a greatest hits album to mark his 50th year in folk

Donovan tells Nick Duerden about receiving death threats, why the world is 'mentally ill', and how he can write a song about anything, from ecology to crumpets

There is a lot of fun to be had in listening to Donovan's latest greatest hits offering, Donovan: Retrospective, released to mark his 50th anniversary in music. Though essentially a facsimile of his many and varied hits collections over the years, his songs remain sublimely evocative of the era from which they sprang. "Epistle to Dippy", for example, could only ever be the product of a man who smoked cannabis in order to throw open the doors of perception, and "The Hurdy Gurdy Man" offers the very headiest of hippy pastiches. But "Season of the Witch" is sinuous and sinister, still a fantastic song, while 1965's "Catch the Wind" – a track that, for many, rendered the then 18-year-old Donovan a mere Bob Dylan copyist – is as purely charming today as it was then.

The man himself exudes a similar charisma, although Donovan in the flesh is more complicated, and convoluted, than such hippy frippery could ever suggest. It is midsummer in London, and pouring with rain. I watch him arrive by taxi, guitar on his back, and scratching his head in confusion on the damp pavement. He looks good for 69, his hair a mop of lank, possibly dyed, curls, while he has made up for the paucity of eyebrow lustre with what looks like eyeliner.

The rain has thrown him. He tells the photographer that he had been hoping to be "happy and gay" for the pictures, but he doesn't want to get wet; could they possibly do the pictures inside? So we head into a music shop in Denmark Street, formerly Tin Pan Alley, a mecca to musicians of a certain vintage.

"Ha," he says. "Well, Tin Pan Alley is the right place for me. I'm a songwriter, aren't I?" A pause. "Though actually, I'm more a poet."

He tells me that he was a poet in his former life too, and that in this one he has always felt an instinctive connection with poems and their creators. He talks about the beatniks Ginsberg and Kerouac, before moving on to ancient Celtic tradition and the even more ancient Indian text, the Upanishads. Donovan, who was born into working-class Glasgow in 1946, was always drawn to the arts and, consequently, to all things bohemian.

"In the 1960s I was convinced that the world was extremely mentally ill," he says. "No question about it: two world wars, a depression, and now the possibility of destroying the planet with nuclear bombs."

He wanted to help, so joined the first bohemian society he could find – in St Albans – where he felt immediately at home. "Since the 1850s, bohemian communities – poets, writers, novelists, dancers – have been cooking up ways to help society by focusing on the human condition, and of course the three levels of consciousness."

The three levels, he explains, are waking, dreaming and sleeping. But there is another level, a fourth, known as transcendental super-conscious vision, which can only fully be accessed through meditation and mantra. Donovan has been both practitioner and promoter of Transcendental Meditation for the past 50 years; he claims to have introduced the Beatles to India. He believes that his study of TM has informed his music in profound ways.

"The way I sing my songs leads the listener into a place of introspection, a state of mind that can trigger self-healing and the kind of profound rest you cannot get from sleep alone." Really? I say. "The Hurdy Gurdy Man" really does that? "Oh yes. Yes."

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Little wonder he thrived in the Sixties, but subsequent decades proved more resistant towards his efforts to calm the masses. The hits dried up, and the business of remaining a pop star threatened to consume him whole.

"Oh, all of us went through terrible things away from the limelight; we went through hell," he says. "The establishment tried to bring me down, for starters." In 1966, Donovan was arrested for possession of cannabis, but claims it was a sting operation. "I was never a hard drug user, you see. I just liked to smoke. Being famous was difficult, dangerous. There were the fatal attractions. Just look at what happened to John."

The murder of John Lennon, I suggest, was surely an isolated incident. Had Donovan's life ever been in danger?

"Well, one fan said to [wife] Linda that she and I had been in love in a previous life and that she was going to kill Linda." He shakes his head. "We kill our heroes," he laments. "We kill our heroes."

After years in the wilderness – first spent living on a Greek island, then Ireland – he was thrown an unexpected lifeline in the early Nineties when the Happy Mondays asked him to tour with them; later, Shaun Ryder briefly married one of his daughters, Oriole. But throughout his fallow years, he never stopped writing.

"Oh, but this is who I am," he says, "It is what I do. I write songs. I am so highly skilled that when I pick up a phrase and then pick up my guitar, a form comes out almost immediately – a song – and once I start, I have to finish it. I've got hundreds and hundreds of songs that nobody has ever heard." The songs form what he describes as "Donovan's Database". It is his life's work, to be appreciated, he suggests, after he has gone.

"Of course, Linda asks whether they need to be heard at all," he says, chuckling, "and I know that when Dylan released many of his unheard songs, certain journalists were shouting STOP! ENOUGH! But I think my fans would be interested."

At home in Ireland, where he lives with Linda, not merely wife but muse ("because a poet needs a muse"), he continues to add to his database daily. There is one new track on Retrospective, a peculiar cod reggae number called "One English Summer", which rhymes "crumpets everywhere" with "Jumbo in the air". He tells me that his songs have special import for songwriters. Songwriters, he says, should take note.

"As a poet, I've always felt like a public servant. I'm providing a service. It's called edutainment. Ed-u-tainment. Because there is so much valuable information in my work. I think my legacy is important because my songs – perhaps more than those of any other songwriter I know – cover every movement from 1965 on, socially and artistically. If you want songs about ecology, I've got ecology songs; if you want songs about spirituality, I've got spiritual songs. "

He smiles beatifically, and it is difficult not to smile with him. At this point, frankly, the conversation could scatter any which way, but instead it comes to an abrupt halt. A fan has entered the shop, and stands before us. He is his early 40s, has a facial twitch and an agitated manner.

"You're… you're Donovan!" he tells him.

Donovan nods. "Yes. It is me," he says.

It could hardly be anyone else.

The 'Donovan: Retrospective' album is out now; his UK tour stars on 3 October at Pavilion, Glasgow

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments