Elvis Presley: How Sun Records boss Sam Phillips discovered a star in 1954

Memphis, 1954, and Sun recording studio boss Sam Phillips dreams of discovering a new sound: a blend of the best of black music and the best of white music. In an extract from his latest biography, Peter Guralnick takes up the story

Sam Phillips had been thinking more and more that the key lay in the connection between the races, in what they had in common far more than what kept them apart. There were always going to be "some bastard white people," he knew, but far more to the point was the spiritual connection that he had always known to exist between black and white, the cultural heritage that they all shared. "Not to copy each other but to just – hey, this is all we've got and we're going to give it to you. This is our Broadway play. This is our Tin Pan Alley. This is what it is. We hope you likeit."

To Marion Keisker, his assistant, he had begun to talk increasingly about finding someone – and it had to be a white man, because the wall that he had run into with his recordings practically proved that in the present racial climate it couldn't be someone black – who might be able to bridge the gap. "Over and over I heard Sam say, 'If I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars!' " And he would always laugh, Marion said, as if to underscore that money was never the point – it was the vision.

One song continued to haunt Sam, a plaintive ballad called "Without You" that the song publisher Red Wortham had given him. There was something about it – for all of its sentimentality, there was a quality of vulnerability about it, and he thought that he'd like to have someone come in and give it a try. The only one who came to mind was a kid who had stopped by the previous summer and for $4 cut a "personal" record for his mother.

The boy had come in to cut another "personal" in January or February – Sam couldn't imagine that he was more than a year or so out of high school – and evidently he stopped by from time to time to talk with Marion. Sam was well aware of that fact because Marion was going on about him. He didn't really know, but when Marion brought up his name for what seemed like the thousandth time, he thought, Why not? The boy had the same yearning quality in his voice, attached to the kind of purity and fervor that you might be more inclined to assign to religious music. Sam had no idea of his full potential, but there was no question, he was certainly different. So he had Marion call him.

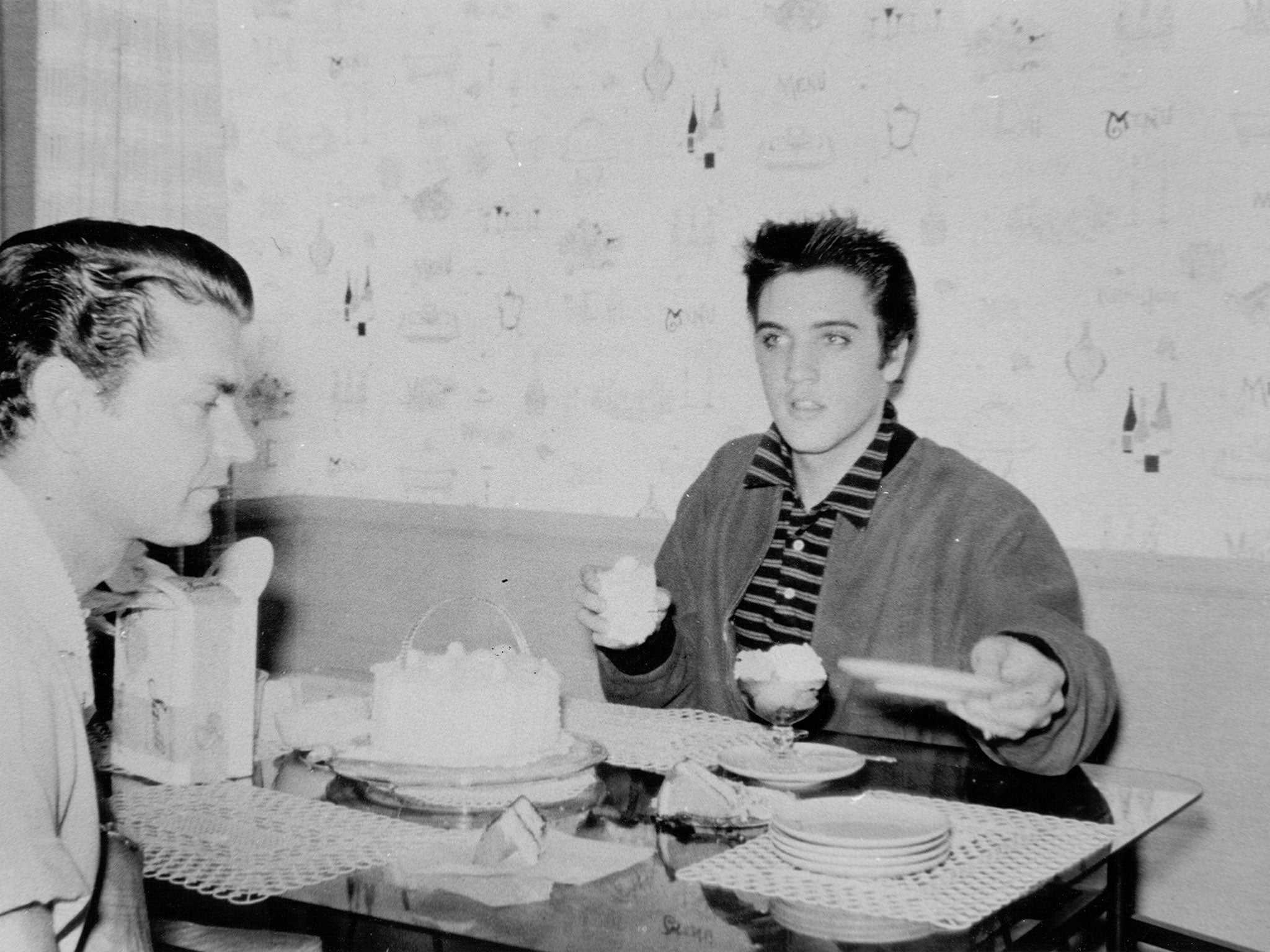

Elvis Presley came into the studio on Saturday, 26 June 1954. He was 19 years old; a good-looking boy with acne on his neck, long sideburns, and long, greasy hair combed in a ducktail that he had to keep patting down. But what struck Sam most was his quality of genuine humility – humility mixed with intense determination. He was, innately, Sam thought, one of the most introverted people who had ever come into the studio, but for that reason one of the bravest, too. He reminded Sam of many of the great early blues singers who had come into his studio, "his insecurity was so markedly like that of a black person".

They worked on the number all afternoon, with Elvis accompanying himself inexpertly on his own beat-up little guitar. When it became obvious that for whatever reason the boy was not going to get it right – maybe "Without You" wasn't the right song for him, maybe he was just intimidated by the damn studio – Sam had him run down just about every song he knew. He didn't need much of an invitation, and he didn't finish every song, but what Sam sensed was a breadth of knowledge, a passion for the music that didn't come along every day.

"I guess I must have sat there at least three hours," Elvis told Memphis Press- Scimitar reporter Bob Johnson in 1956. "I sang everything I knew – pop stuff, spirituals, just a few words of [anything] I remembered." Sam watched intently through the glass of the control room window – he was no longer taping, and in almost every respect this session had to be accounted a dismal failure, but still there was something. . .

Every so often the boy looked up at him, as if for approval: was he doing all right? Sam just nodded and spoke in that smooth, reassuring voice. "You're doing just fine. Now just relax. Let me hear something that really means something to you now." Soothing, crooning, his gaze locked into the boy's through the plate-glass window he had built so that his eyes would be level with the performer's when he was sitting at the control room console. He didn't really know if they were getting anywhere or not, it was just so damned hard to tell, especially when you were dealing with someone who was obviously unaccustomed to performing in public.

Then again, it was only from just such a person – pure, unspoiled, as raw, as untutored as anyone who had ever set foot in this studio – that he felt he could get the results he was looking for. He knew this boy, he knew where he came from, he could intuit all the things they had in common in background and sensibility . What you could never tell was whether it would ever add up to anything. He sent the boy on his way, exhausted.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

There was something about him – Marion kept after him all week about how the session had gone. One day they were sitting with [guitarist] Scotty Moore, and Marion brought up the boy again. "This particular day," Scotty said, "it was about five in the afternoon. Marion was having coffee with us, and Sam said, 'Get his name and phone number out of the file.' Then he turned to me and said, 'Why don't you give him a call and get him to come over to your house and see what you think of him?' [Bass player] Bill Black lived just three doors down from me. Sam said, 'You and Bill can just give him a listen, kind of feel him out.' "

Scotty called Sam at home the following evening. They had had their audition and it had gone much like the one Sam had conducted. Bill had been none too impressed, and Scotty's wife had just about bolted out the back door when the kid arrived wearing a black shirt, pink pants with a black stripe, white shoes, and that long greasy ducktail. They ran through the same assortment of songs – hillbilly, pop, Billy Eckstine's "I Apologise"; the Ink Spots' "If I Didn't Care"; Hank Snow and Eddy Arnold's latest hits – and a Dean Martin-styled version of "You Belong to Me".

They were all ballads, all sung in a yearning quavery tenor that didn't seem ready to settle anywhere anytime soon and accompanied by the most rudimentary strummed guitar. Well, Sam, said, what did he think?

It was in a sense Scotty's decision – this might be the vocalist he had been looking for to sing with his band. "Well, you know, he didn't really knock me out," said Scotty, never less than completely honest. "But the boy's got a good voice." "You know, I think I'll just call him," Sam said, "get him to come down to the studio tomorrow – we'll set up an audition and see what he sounds like coming back off of tape." Should he bring the whole band? Scotty asked – The Starlite Wranglers? No, Sam said. "Just you and Bill, just something for a little rhythm. No use making a big deal about it."

The three of them showed up the next night around seven. There was some desultory small talk, Bill and Scotty joked nervously between themselves, and Sam tried to make the boy feel at ease, carefully observing the way in which he continued to both withhold himself and thrust himself into the conversation at the same time. At last, after a few minutes of aimless conversation and letting them all get a little bit used to being in the studio, Sam turned to the boy and said, "Well, what do you want to sing?"

This occasioned even more self-conscious confusion as the three musicians all tried to come up with something they knew and could play – all the way through – but after a number of false starts they finally settled on "Harbor Lights", which had been a big hit for Bing Crosby in 1950, and worked it through to the end. Then they tried Leon Payne's "I Love You Because", a beautiful country ballad that had been a number one country hit for its author in 1949, and a number two hit for Ernest Tubb, also on the hillbilly charts, the same year.

They tried each song again and again – each take was slightly different, but each time the boy flung himself into the performance, clearly trying to make it new. Sometimes he simply blurted out the words, sometimes his singing voice shifted to a thin, pinched, almost nasal tone before returning to the high, keening tenor in which he sang the rest of the song. It was as if, Sam thought, he wanted to put everything he had ever known or heard into one song.

Scotty's guitar part was almost invariably too damn complicated, he was trying too hard to sound like Chet Atkins – but then there was that strange sense of inconsolable desire in the voice, there was the unmistakable thrill of hearing free, unfettered emotion being conveyed without disguise or restraint.

Sam sat in the control room, trying to look fully engaged but unconcerned at the same time. Every so often he would come out and change a mike placement slightly, talk with the boy a little, not just to bullshit with him but to try to make him feel more at home. He was happy enough with the interaction between the musicians.

There was a reason he had chosen them to accompany the boy. Scotty was the best-natured person in the world – he never made any demands and he didn't take himself too damn seriously. Bill on the other hand was a cut-up. He was a natural mixer who could get a laugh out of a perfect stranger. And while he was no more a virtuoso on his instrument than Scotty, he could slap that bass to create the kind of driving, propulsive effect that Sam felt this little trio was going to need if it was ever going to be able to get across.

But still, they hadn't got anything usable and he wasn't sure exactly what to do. You never wanted to quit a session like this too early – you might just kill any chance of confidence developing over time. But it was a real question as to how long you wanted to keep things going, too. Staying with it too long could create a kind of mind-numbing quality of its own, it could smooth over all the rough edges you were trying to bring out and banish the very element of spontaneity you were trying to achieve.

Finally they decided to take a break. It was late, the boy was clearly discouraged, and everybody had to work the next day. Maybe, Sam thought, they ought to just give it up for the night, come back on Tuesday and try again. Scotty and Bill were sipping Cokes, not saying much of anything. Sam was doing something in the control room and, as Elvis explained it afterwards, "this song popped into my mind that I had heard years ago, and I started kidding around with [it]."

It was an up-tempo song called "That's All Right, Mama", an old blues number by Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup. "All of a sudden," said Scotty, "Elvis just started singing this song, jumping around and acting the fool, and then Bill picked up his bass, and he started acting the fool, too, and I started playing with them.

"Sam, I think had the door to the control booth open. I don't know, he was either editing tape or doing something. And he stuck his head out and said, 'What are you doing?' And we said, 'We don't know'. 'Well, back up,' he said, 'try to find a place to start, and do it again.'"

The rest of the session went as if suddenly they had all been caught up in the same fever dream. They worked on the song. They worked hard on it, but without any of the laboriousness that had gone into the session up to this point. Sam worked to get them to see the song in more of a flow. He got Scotty to cut out the conventional turnaround and cut down on all the stylistic flourishes that were mucking it up. "Simplify, simplify!" was the watchword.

Bill's bass became more of an unadulterated rhythm instrument – it provided both a slap beat and a tonal beat at the same time – all the more important in the absence of drums. They continued to work on it, refining the song but the centre never changed. It always opened with the ringing sound of Elvis's rhythm guitar, up till this moment almost a handicap to be gotten over. Then there was Elvis's vocal: loose and free and full of confidence, "sounding so fresh," Sam said, "because it was fresh to him." With Scotty and Bill finally falling in with an easy swinging gait that was the very essence of everything Sam had dreamt of but had never been able to fully imagine. There were no studio tricks employed. He didn't even use his new discovery of slapback, which he had applied primarily to the guitar on the two other completed selections. There was just the purity of the music.

The first time Sam played it back for them, "we couldn't believe it was us," said Bill. "It just sounded sort of raw and ragged," said Scotty. "We thought it was exciting, but what was it? It was just so completely different. But it just really flipped Sam."

And the boy? By the end of the evening there was a different singer in the studio than the one who started out the night. For Elvis, clearly, everything had changed. Sam sat in the studio after the session was over and everyone had gone home. He was bone-weary, but he just wanted to savour the moment.

When he got home, he woke up Becky, and, as she would always remember it, "he was excited, he was happy, and he announced that he had just cut a record [that was] going to change our lives. I didn't understand at the time what he meant, but it did. He felt that nothing would ever be quite the same again."

© Peter Guralnick, 2015. Extracted from 'SAM PHILLIPS: The Man Who Invented Rock'n'Roll' by Peter Guralnick. Published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson on 12 November, priced £30 in hardback and £14.99 in ebook.

Readers of The Independent may order copies of 'Sam Phillips' for the special price of £25 by calling 01903 828503 and quoting ref no RI080

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks