Taylor Swift says she does not use music as a weapon but her lyrics and song titles say otherwise

An extract from a new book looks at how the world’s biggest pop star became the hero of broken-hearted teens by building her career on passive-aggressive score-settling

“I’ve never thought about songwriting as a weapon,” Taylor Swift said with a straight face to an interviewer from Vanity Fair while the magazine was profiling her in 2013.

No, not Taylor Swift. Not the author of songs like “Forever and Always”, written in the wake of her relationship with former boyfriend Joe Jonas, the better-looking Jonas brother, and featuring this lyric: “Did I say something way too honest, made you run and hide like a scared little boy?”

Not her, who wrote/sang about her relationship with the actor Jake Gyllenhaal, “Fighting with him was like trying to solve a crossword/ And realising there’s no right answer.”

Not Taylor, who leaves the impossible-to-crack clues in her liner notes for each song by capitalising a variety of letters that spell out the subjects in a very essential way: “TAY” for a song about ex-boyfriend Taylor Lautner; “SAG” for the Gyllenhaal one (as in “Swift And Gyllenhaal”, or that they’re both Sagittarius. I don’t know).

For Taylor Swift to pretend that her entire music career is not a tool of passive aggression toward those who have wronged her is like me pretending I’m not carbon-based: too easy to disprove, laughable at its very suggestion.

The masterstroke of all of this passive-aggression is, of course, “Dear John,” a single on her album Speak Now. Here are some of the lyrics to “Dear John”: “All the girls that you’ve run dry have tired, lifeless eyes/ ’Cause you’ve burned them out/ But I took your matches before fire could catch me/ So don’t look now/ I’m shining like fireworks over/ Your sad, empty town.”

Taylor wrote this in the aftermath of her relationship with renowned rake John Mayer, a man who committed the sin of breaking the heart of a post-Pitt Jennifer Aniston, among others.

Taylor’s “Dear John” is a masterclass in passive-aggression. First, consider Taylor’s use of the generic “Dear John” letter for this specific John – there’s that plausible deniability again – as if to make it sound like a goodbye letter to anyone, when really it’s a goodbye letter to someone.

But she also maintains that she’s innocent, having told The Times: “I can say things I wouldn’t say in real life. I couldn’t put the sentence together the way I could put the song together.” It’s not that she didn’t want to say this to your face, John. It’s just that she couldn’t.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

See, Taylor was, according to lore, a chubby geek in middle school. She was abandoned by her peers in sixth grade, just when her songwriting powers were coming to fruition, and so just as her gift began to sprout, so did her ability to articulate them and, just a couple of years later, publicise them.

It was a dream come true for a rejected-feeling girl who was coming into her own as a tall, dazzling blonde with a microphone and a following. Is there any one of us who kept a diary without wishing deep down that someone would find it and understand us fully, down to the ugliest detail? Is there anyone among us who didn’t hope that the world would learn from that diary exactly how the world had wronged us?

That’s how Taylor Swift became the hero of all us losers, of anyone humiliated in middle school, the publicly dumped in high school, or anyone who ever realised during the car ride home the perfect comeback that would now go unsaid. Taylor puts it out there, and out there it stays.

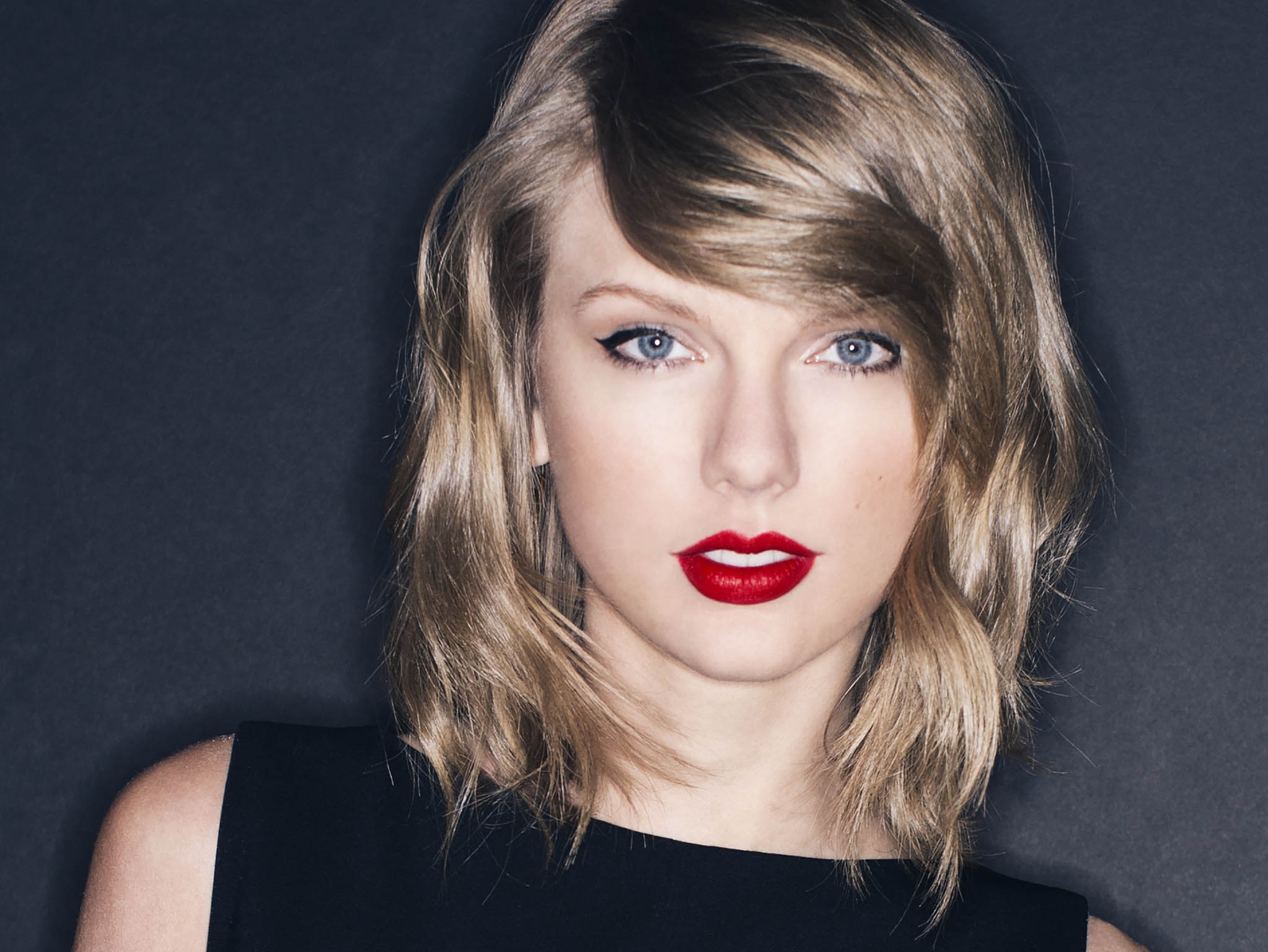

In a way, she was made for this. She was born with the face of an accusation. Her eyes, which see everything and narrow naturally; upturned, judge-y nose to look down past; lips that tend toward pursing.

Yet she was also born lovely, with a sweet, thin voice and an engaging smile. She’s smart and tall, and she’s thin now. Who would not love her? In fact, for those of us who were chubby youths, who had no friends, the invention of Taylor Swift is no less than the invention of a super-robot sent through time and space to lure the mean girls and mean boys into loving us, and then break their hearts and tell the world what scum they are. We couldn’t have dreamed it better.

Taylor’s denials are another layer of performance art. Because has there ever been a more passive-aggressive profession than writing? Writing is first born of a need to explain oneself, and it is co-morbid with the desperate loneliness of an ostracised, chubby middle-schooler, like she was and, well, like I was.

The popular kids can explain themselves to each other. Only the lonely are left to their writing. It’s through the tools of observation that we learn to hone an otherness… we begin to define ourselves from the way we are different. And slowly, slowly, we spend so much time pretending that someone is listening that we often don’t know how to change modes once people are.

We are generally people who like to pretend that our childhoods happened to another version of us, that we don’t carry the scars that we do. So I play it safe. I don’t refer to people who have wronged me; I don’t ever put in writing the thing I should have said, the thing I’m still kicking myself for not saying.

I don’t know if that makes me dumber or smarter than Taylor, and I certainly don’t know if my refusal to use my work as a tool of passive-aggression makes me braver or more afraid.

I have become someone who is only perfectly vengeful in my head. The closest I’ve gotten is writing an essay about a man who broke my heart and changing his name from Garry to Gary. (But there’s hope, isn’t there? Here I just admitted what I did! Suck it, Garry!)

Taylor exists as our id. She alone possesses the chutzpah to play innocent as she boldly winks at what she’s done in a forum more public than even the most viral article.

But it’s also through her that we can continue to fantasise about a revenge most perfect, an aggression so passive that no one sees it coming, that no one can confirm it once they’ve been hit. That day might be around the corner, and it’s Taylor who allows us to dream of it: dream of a time when the stings of the past are made better through the public hanging of dirty laundry, a time when we say the perfect thing in the moment when it most counts, a moment when we finally get the last word.

It’s on that day that we, too, will have our most perfect aggression realised. It’s on that day you will find us shining like fireworks over their sad empty towns.

“Revenge of the Nerds” is a chapter from ‘Here She Comes Now: Women in Music Who Have Changed Our Lives’ edited by Jeff Gordinier and Marc Weingarten, which is out in April 2016. Taffy Brodesser-Akner is a contributing writer for ‘The New York Times Magazine’ and ‘GQ’. She won a 2014 New York Press Club award for entertainment writing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments