Giles Duley: The photographer finding hope in the darkest moments of the refugee crisis

‘Even in the worst times, even when you think all hope is lost, the human spirit is incredible and people will always find a way to rebuild their lives’

From a hospital bed in Birmingham where he was convalescing after losing three limbs in an explosion in Afghanistan, photographer Giles Duley watched the war in Syria unfold on the TV.

At that moment in 2011, he realised that documenting the then arising refugee crisis would be the most significant mission of his career.

“Before I got injured my work was documenting the effects of conflict and I was always very focused on the legacy that people lived with after wars,” he explains.

“But after I got injured, I really felt that I was living with my own legacy of war and something that I would have for the rest of my life so it became even more important to me.

“Within that I knew that what was happening in Syria was on a scale that was unprecedented.

“That’s why I knew it was something that was so important that I would have to be documenting it.”

Tasked with “the greatest brief a photographer can be given: ‘follow your heart’” from the UNHCR in 2015, Duley journeyed through 14 countries to capture the desolate and inconceivably treacherous passage awaiting the millions of refugees forced from their homes by the deadly conflict.

He travelled across Europe, including to Greece, Macedonia, Germany, Finland and France, where the refugee crisis was already garnering much media coverage, but always felt it was particularly important to look beyond the continent to the Middle East.

It was there, in countries such as Jordan, Iraq and Lebanon, that he could see the impact was being felt more intensely. “Lebanon had a population of five million people and it had more than a million refugees living there,” he says.

By this point “everybody was covering the story”, detailing the journeys of people crossing borders and the Mediterranean in the hope of finding safety and sanctuary, and a place to temporarily make their home.

But that meant Duley could do what he does best and focus on the lesser-known tales of conflict.

He admits his photographs of people crossing to Lesbos and walking up to Germany are his “least favourite” of the series because they are the most traditional documentary photographs.

They can lack, he says, intimacy and the process means you do not get to know the people because they are constantly moving and transient.

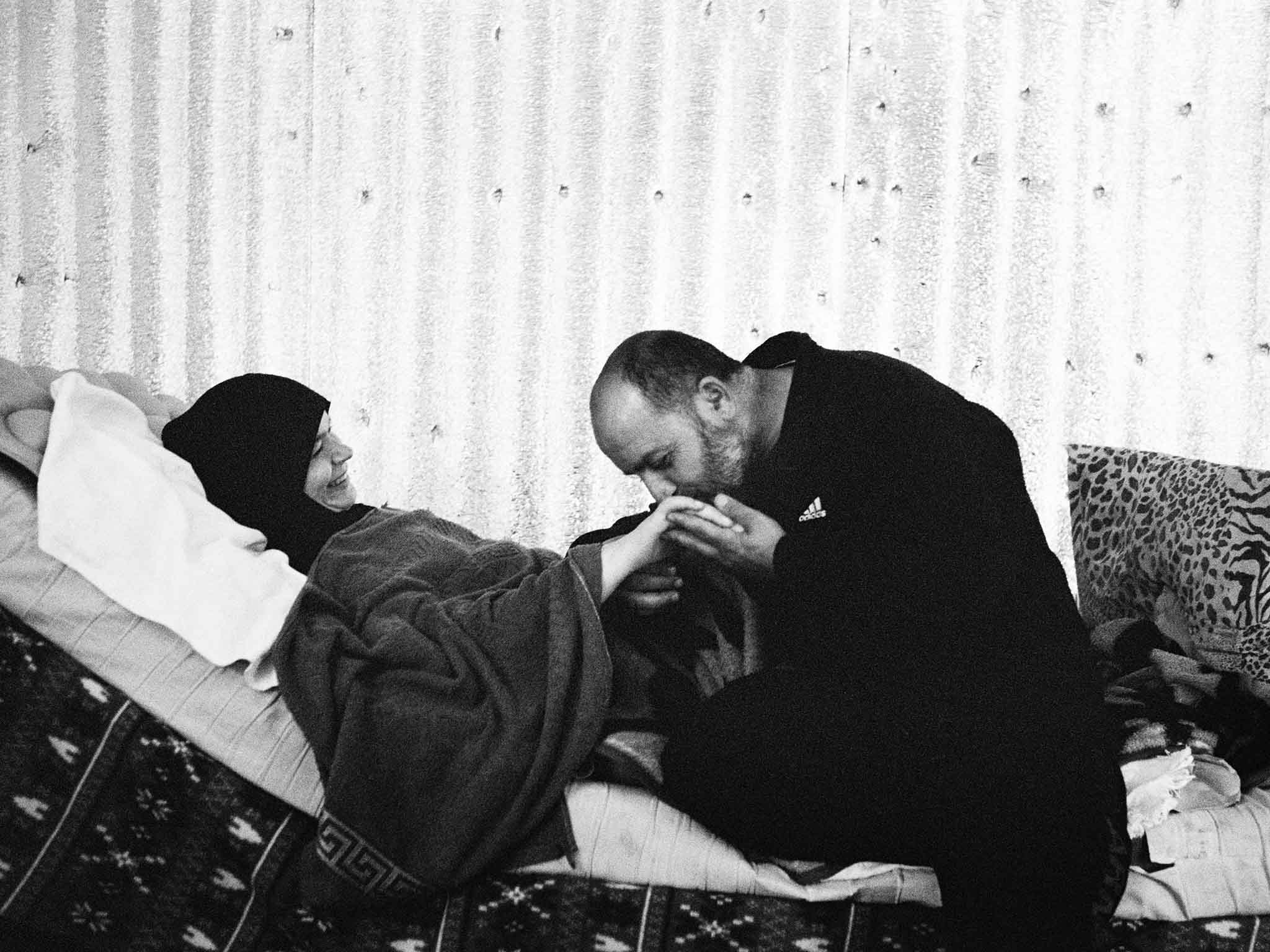

“I felt I could do it in a different way,” he says. “I realised my role was to humanise some of the stories.

“Everything had become about the statistics, the fact that there were millions of refugees and a lot of scenes of mass exodus, people in their thousands, things like that.

“I wanted to break it down to families and individuals.

“My work has always been that, always been about the little intimacies within one family and I didn’t think that was coming across. That’s why I wanted to do it.”

At the heart of this, is Duley’s awareness of the ongoing narrative for the people he documents and forms bonds with.

He quickly became conscious of the fact that stories do not end when he leaves and wraps up a project – for the subjects, a photographer’s presence would typically be a fleeting moment of distraction before the irrepressible feeling of needing to survive while in a perpetual state of uncertainty goes on.

“The people we document, their stories continue and one of the things that I’ve become increasingly interested in is going back and revisiting families, especially for refugees because the reality is that they are stuck in limbo and their lives don’t move forward,” he says.

“That in a sense is the story, the fact that nothing changes.

“A lot of newspapers, magazines and media outlets, they’re not really interested in that, they would say, ‘Why would you go back? You’ve already done that story’.

“I have that freedom and the ability to be able to go back over various times and I think it’s one of the most important elements of my work to tell that story again and again.

“It reinforces the fact that nothing changes for the refugees.

“In some of the images, you can see the kids growing up and you can see them at different points in their lives – and you can really get that sense of how hard it can be to imagine what that’s like over three, four, five years in a camp for those children growing up.”

Sometimes it is painful to witness stories evolve, and the saddest thing Duley says he has seen in terms of change when returning to visit families is the darkness that descends on them when they lose hope.

He explains: “At the beginning people were always saying to me, ‘we’ll go back to Syria in six months’, and then ‘we’ll go back next year’, and then people started to change and started to say, ‘we’ll never go back because the country is destroyed’.

“I remember one of the refugees I photographed on a train in Macedonia and I asked him why he left, because his family was still in Syria.

“He said, ‘I was the first to lose hope’. I think that’s a really powerful idea that actually hope is what keeps people going.”

The remarkable hope displayed by some of the people Duley met during this work had a profound impact on him, during even some of the most distressing times.

It was while visiting a hospital in Iraq run by medial NGO Emergency, for which he is a trustee, that he chanced upon one of the brightest glimmers of hope that shone from within the darkest depths of the unimaginable heartbreak and destruction left in the path of war.

“Of all the trips I’ve done, covering I don’t know how many different conflicts and certainly the effects of so many different conflicts, I can’t think of any other experience that I found more upsetting than going to Emergency’s hospital in Erbil,” he says.

“The amount of civilians being brought in from Mosul was on a scale like I’ve never seen, and I’ve never seen so many families absolutely destroyed.

“I was left feeling completely and utterly overwhelmed and I always try to see the positive when I’m doing a story and create dignity, but in that hospital I just felt devastated.

“I felt really negative about everything.

“But it was some of the injured children there that were the ones that broke me out of that.

“In particular there was one ward where there were two young boys who’d lost their legs.

“They were both affected in different ways; one of them wasn’t eating and was very depressed so every day I would go to sit on his bed and eat with him. We’d just share a meal to slowly encourage him to eat.

“Then one day they started playing some music on their phones and one of the songs was called ‘Take me back to Mosul’. The reality for most of the refugees forced from their homes by conflict is that they just want to go home.

“They were playing this song and as I was taking a photograph of the young boy he did the V for victory with his fingers and it just reminded me again that even in the worst times, even when you think all hope is lost, the human spirit is incredible and people will always find a way to rebuild their lives.

“The resilience of these people is what inspires me.

“I have my own personal experience of losing three limbs, being stuck in a hospital and I remember at times thinking if I would ever work again, ever do anything, and it’s amazing what the human spirit can achieve.

“In that moment I would say covering the fighting in Mosul was the darkest time for me as a photographer in terms of being overcome and overwhelmed by tragedy but it was the spirit of the patients that I was photographing that gave me hope again.”

Duley’s own hope for his work is that everyone will recognise there is always some kind of helpful action that can be taken that will have a huge impact on others.

“It’s very easy to feel overwhelmed by all the stories of refugees and it’s very easy to think there’s nothing you can do,” he says.

“But it’s my belief that each one of us can do something positive and through that can create ripples that will affect other people’s lives.

“The one thing I would say is even if it is something small, you can do something and you can help and we all need to do that.”

Giles Duley’s photography will be on display at the exhibition ‘I can only tell you what my eyes see’ at The Old Truman Brewery, London until 15 October and then at the Triennale Museum, Milano from 24 October to 12 November and at Casa Emergency, Via Santa Croce, 19 – 20122 from 27 October to 24 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments