War in the Sunshine: The British in Italy 1917-1918

With the ability to find beauty in foreign battlefields during the First World War, work by painters and photographers who captured the British experiences in Italy with their own eyes is exhibited at Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art

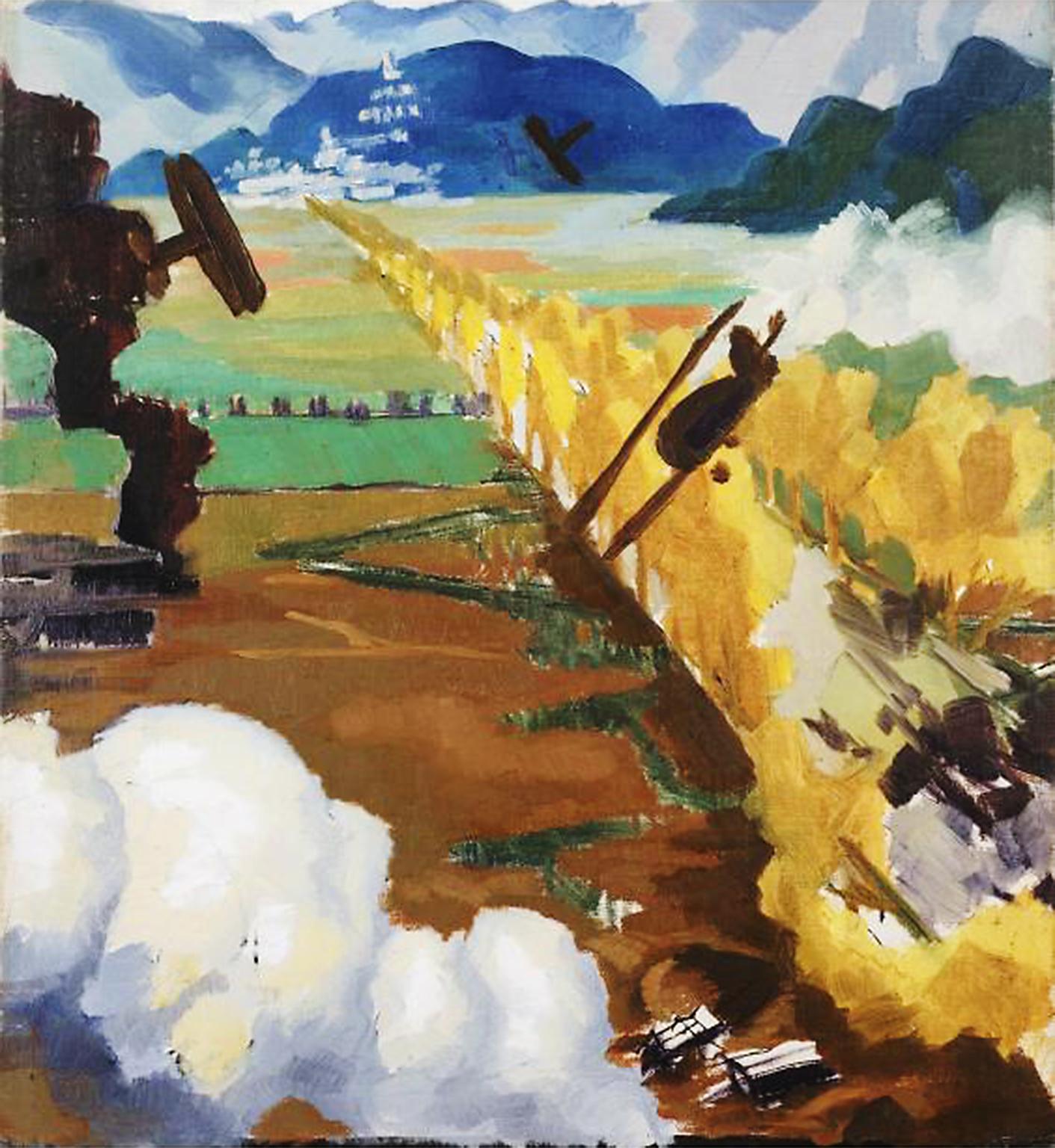

Suspended over a landscape picked out in orange and emerald green, a distant town sparkling white against the brilliant blue of the mountains, you would hardly know that this is the middle of a bombing raid. Nearby aircraft are of no more consequence than birds in the sky, and a plume of smoke blends in with the rich brown of the fields below.

Like many artists posted to more far-flung locations during the First World War, Sydney Carline (1888-1929), a top fighter pilot and from 1918 an official war artist attached to the RAF, was delighted by his unfamiliar surroundings. Part of the expeditionary force sent to assist the Italian Army after its defeat at Caporetto in October 1917, Carline was capable of drifting into a landscape-inspired reverie while on a bombing mission. As official war artist he flew his Sopwith Camel with a drawing board across his knees, although his instincts as a fighter pilot meant that he always kept his machine guns loaded.

Marking its reopening after a five-month refurbishment, a new exhibition at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art explores British experiences in Italy through the eyes of three artists. Rediscovered by art historian Dr Jonathan Black in the archives of the Imperial War Museum, paintings and drawings by the “fighting painter” Sydney Carline join works by official photographers Ernest Brooks (1878-1941) and William Joseph Brunell (1878-1960).

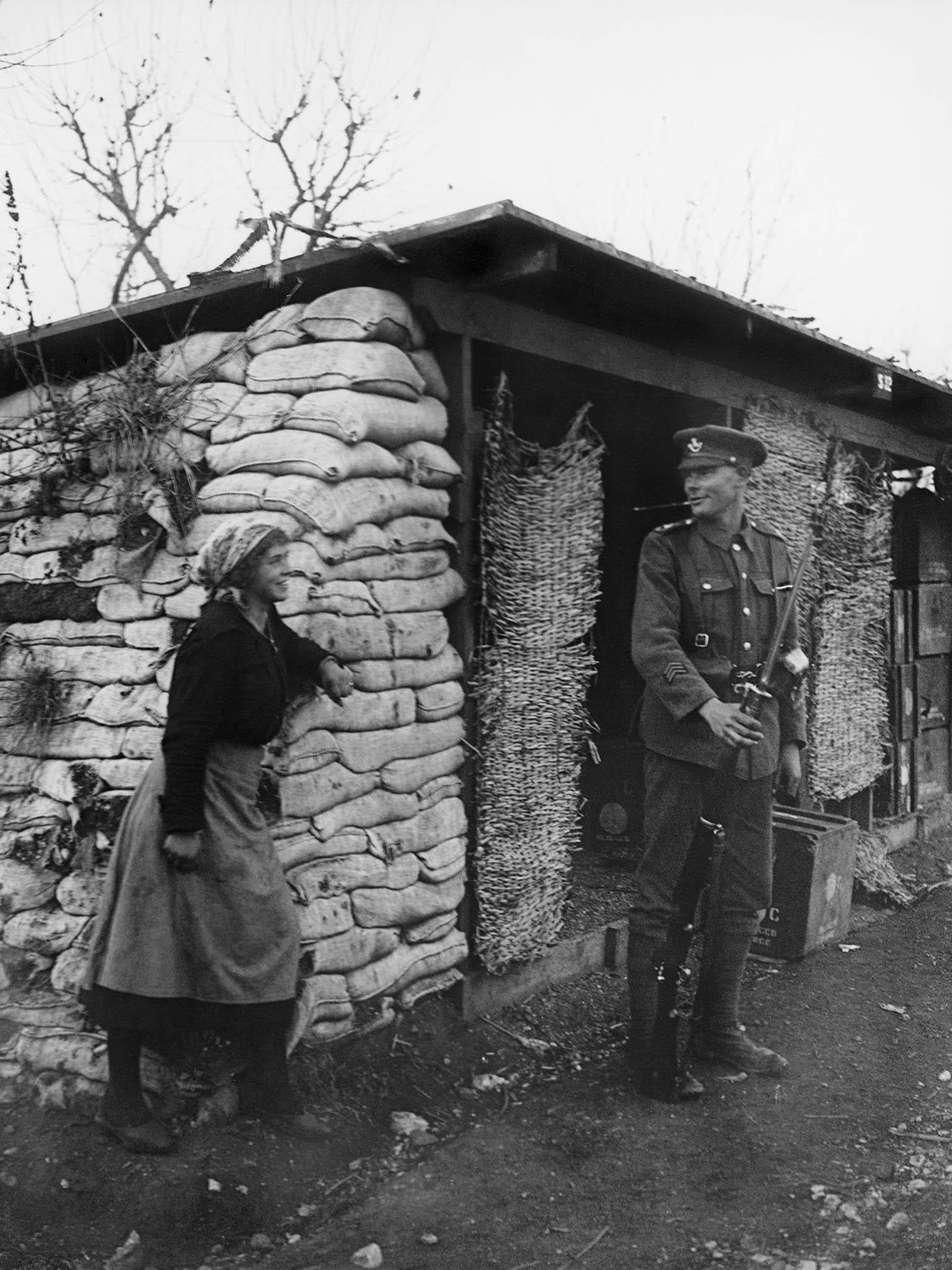

These three very different men offer a vivid impression of the British presence in the Veneto, where soldiers lived among poverty-stricken civilians, many of whom had had to flee their homes, and managed a sometimes delicate relationship with the Italian Army.

Of course it wasn’t just artists who were susceptible to the thrill of unfamiliar surroundings and a culture very different from their own. For the average Tommy, sent to Italy after months of deadlock on the Western Front, the prospect of a spell in the sunshine must have felt akin to a holiday. In his book With the Mad 17th in Italy, one Major Hody describes the excitement that met rumours of a move south: “From Flanders to Italy. What a contrast indeed! From a country of seething slush and mud, with dark skies and continual dampness, rain and depression, to a land of warmth, sunshine and blue skies.”

The reality was less idyllic and Italy proved a punishing terrain. After the mud of Flanders the swamps north of Venice provided little respite and the mountains presented a harsh new challenge, with one Red Cross volunteer comparing the slopes to the “steepest faces of Arthur’s Seat”. Even so, in memory at least, the lure of the Mediterranean seems to have prevailed, with tales of the impoverished but welcoming Italians throwing figs and oranges to the troops as they passed through on trains. As the historian Mark Thompson writes in the exhibition catalogue: “Working-class men, experiencing the sensuous romance of the south for the first time, were as captivated as their carriage-borne predecessors had been on the Grand Tour.”

Of the three men featured in the exhibition, Brooks was probably the hardest to impress. A former soldier with a distinguished record in the Second Boer War and one of the first official war photographers, Brooks took a dim view of the ill-disciplined and demoralised Italian Army. It is testament either to the charms of the place, or perhaps just to the close-knit living conditions, that Brooks was tempted away from purely military subjects to capture the day-to-day interactions between soldiers and civilians, including a beautiful picture of British soldiers sitting down to eat with an Italian family. By all accounts, the British were slow to take to pasta and gnocchi, but adapted more readily to vino rosso.

Italian women were employed by the British Army Service Corps to an extent unprecedented in the Italian military, and photographs of women cooking and washing clothes give a sense of an unlikely, makeshift community. Pictures of women loading and unloading barrels are an astonishing testament to the importance of rum as a British Army staple, still more to the logistics of ministering to some 70,000 troops.

When Brooks left Italy to return to the Western Front in September 1918, he was replaced by Brunell, an unknown quantity whose poor health prompted him to volunteer as a photographer to avoid conscription. Brunell lacked Brooks’s military background and sensibilities, and his pictures of picturesque ruins, curious arrangements of objects and dignified portraits suggest a sensitive and romantic disposition. Italian peasant women with their olive complexions were clearly fascinating, perhaps a little awe-inspiring for a young soldier, and Brunell’s portrait of a young Italian woman employed by the British Army could pass for a Renaissance Madonna.

While it offered a degree of exoticism, Italy also offered a comforting reminder of how England might once have been, the women’s timeless clothing and the animals put to work on the land evoking a bucolic paradise that chimed with a nostalgic vision of home. Photographs of oxen and donkeys recall drawings made by Stanley Spencer in Macedonia, where he served with the Royal Army Medical Corps. For Spencer, nicknamed “Cookham” by his Slade School peers because of his peculiar attachment to his home village, his posting to Macedonia was, as for so many soldiers, his first experience of travelling abroad. For a devout Christian, the blazing sunshine, simple clothing and apparently primitive farming methods seemed to be straight out of the Bible, and he described in his notebook a “spiritual world”, with “oxen under yokes; men passing slowly on mules; distant, rugged mountains”.

While the most famous images of the First World War convey its horror, the impulse to find beauty was an instinctive, frank response to the novelty of lands and people encountered in a fluke of circumstance. Spencer, a man who would surely never have left Cookham were it not for the war, conceded: “I would not have missed seeing the things I have seen since I left England for anything”, and it is the sheer humanity of an inquisitive spirit undented by war that gives the pictures of Carline, Brooks and Brunell their appeal.

The exhibition is open until 19 March 2017. Visit estorickcollection.com for more information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments