The culture of fear: In an age of lies, the fiction writer is king

Andy Martin investigates the role the thriller genre plays in shaping political narratives – and how it may be contributing to the collapse of society

Sanders Theatre. Harvard University. September 2015. Stephen King is interviewing Lee Child regarding his (then) latest novel, Make Me. The auditorium has seating for a thousand. It is packed. Afterwards, while Stephen King rushes off to receive his National Medal of the Arts from President Obama, the queue of people lining up to have their copy of the book signed by the author is not just long, it snakes into the night and I can’t even see where it ends. I know it takes hours to get from one end to the other.

Fast forward more than a year. USA Main Street. November 2016. Massive queues form all over the nation. To cast a vote in the election.

Fact: some of these people, the ones queuing up to have the latest Jack Reacher signed by Lee Child, and the ones queuing up to record their vote, are the same people. Some of them, a lot of them, voted for the Republican outsider figure, Donald Trump.

Question: like a detective investigating a mystery – could there be a connection? More broadly, has the paranoid genre of thriller fiction created an atmosphere, a mentality, a zeitgeist, in which we are more likely to plump for a certain kind of political narrative? In a word, to vote for fear. Or out of fear. Or both.

Please don’t shoot me, fans of Lee Child (and others). Not yet anyway. I am not blaming Lee Child personally for the election of Donald Trump. I am not pointing the finger at anyone in particular. Not even, for example, at such prime exhibits as Tom Clancy (conservative Republican and firm friend of Ronald Reagan) or Frederick Forsyth (who sniffs out right-wing causes the way a philatelist collects stamps). For one thing, the author cannot control and cannot be held accountable for the interpretation of his texts. For another, the issue far transcends any one writer, and even the written word, and extends in the direction of Hollywood and beyond.

And it’s not just America. Just last month, following the publication of the 21st in the Jack Reacher series, a three-hour long queue formed at Waterstones, Plymouth, UK. Likewise, on this side of the Atlantic, we have Brexit, which (even without mentioning the name of Nigel Farage) manifests an inescapable congruence with Trumpist nationalism.

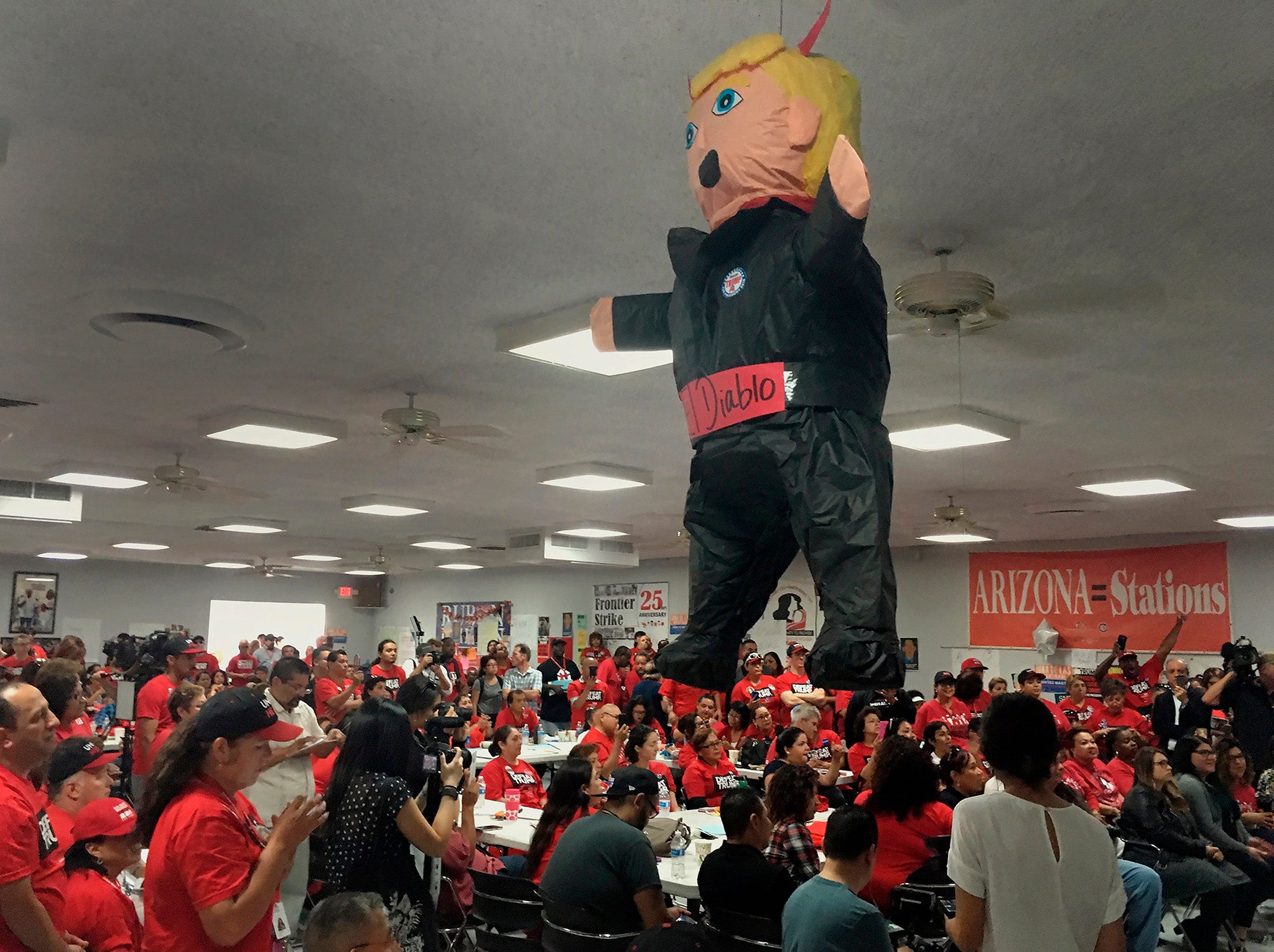

Pulp fiction – or, more specifically, pulp film – won the election. In America and Europe we are living in an era best summarised in the title of the classic thriller, Cape Fear (adapted from The Executioners by John D MacDonald). Towards the end of the election campaign, the Clinton camp came up with the slogan, “LOVE TRUMPS HATE”. That slogan lost. The alternative view, presumably is “HATE TRUMPS LOVE”. Or possibly, “TRUMP LOVES HATE”. All parties now, in a post-truth world, speak of “narrative”.

This is how Harold Bloom, Sterling Professor of the Humanities and English at Yale University, and author of The Anxiety of Influence, put it (in an email): “Trump won the election because 62 million Americans live in a state of virtual reality. They no longer know what facts are. They’re also consumed by resentment, racial prejudice, and the deep fear that their America is vanishing forever. It will. Trump will see to that.” In terms of genre, noir defeated romance. We don’t vote for Mills and Boon. We vote for The Terminator and a Fistful of Dollars. We vote for Dirty Donald.

On a poll of crime writers I happen to know (conducted, scientifically, in a pub in London the other night) a vanishingly small number are pro-Trump. Most are explicitly anti. Consider, for example, Child’s Make Me. Reacher’s main antagonist, the initiator and CEO of a monstrous yet mysterious criminal enterprise that underpins the small town of Mother’s Rest, is never named, only described: “He had blow-dried hair like a news anchor on TV”. Sound familiar? I can’t say exactly what happens to him, but it’s nothing pleasant.

Child’s massive vigilante hero, Jack Reacher, is anti-racist and anti-fascist. He hates red necks. Hence this scene in a truck-stop bathroom, talking to a guy who has expressed scorn for a “beaner” (pejorative for “Mexican”):

“Well, I’m smarter than you,” [Reacher] said. “That’s for damn sure. But then, that’s not saying much. This roll of paper towels is smarter than you. A lot smarter. Each sheet on its own is practically a genius, compared to you. They could stroll into Harvard, one by one, full scholarships for each of them, while you’re still struggling with your GED… The bacteria on this floor are smarter than you.”

In Nothing to Lose, similarly, Reacher denounces evangelical Islamophobic sentiments and critiques American foreign policy, notably in Iraq, quoting the actual words of soldiers on the frontline who had written to the author. Still, however, unleashing a torrent of hate mail and assassination threats from some of his more fundamentalist patriotic readers. “Burn in hell, Child!” was one of the more polite messages.

NRA-loving Clint Eastwood, he ain’t. He works against the grain of his own chosen form. “I hate the big guy,” says Child, “Reacher wouldn’t vote Republican.” But then Reacher is a big guy (quite literally, 6’ 5” and 250 lbs). So (as Harold Bloom would say) there is an agon – a principle of self-deconstruction – at the heart of the thriller. It may even be what makes it so gripping.

When I asked Jo Nesbø, author of The Snowman, about this, he said, “Wow. Right now I’m in the very intense process of helping a friend with a treatment for a movie that deals with a certain paranoia, the hidden agenda-paranoia.” There always is a hidden agenda. But it is the hidden, the repressed, the buried bodies, that make literature work.

I think this was the point made by Marx and Engels over 150 years ago, regarding their favourite writer, Balzac. On the face of it, they argued, Balzac was a conservative royalist in post-Revolutionary France, harking back nostalgically to the days of feudalism. But the novels of the Comédie humaine tend to dramatize and buy into the rise of capitalism and the bourgeoisie thus, ultimately, according to the iron laws of dialectical history, leading to the dictatorship of the proletariat. So Balzac was really a good communist at heart. In other words, the intention of the author counts for nothing. It’s all about the readers and their interpretation. Or, they might have added, had they been able to foresee the dictatorship of the Hollywood production company, the movie adaptation of the original. And, even more shrunken and impoverished, the movie poster.

The neo-realist novel is dense and complex and polyphonic. The medium of the film tends towards myth and monomania. You can take the lyrical labyrinth that is Never Go Back, feed it through the Hollywood sausage machine and you end up with a movie tie-in paperback with Tom Cruise’s face all over it, linked to the Stars and Stripes, the Capitol, and a gun. The movie is reductionist. There is shrinkage. Nearly everything is lost in translation. But what remains?

Noir is by definition a paranoid genre, in cahoots with conspiracy theory. We are surrounded by bad guys. Or serial killers/drug barons/human traffickers/world-class criminals of every stripe. We need a saviour. The writer David Thomas, who also writes as “Tom Cain” and collaborated with Wilbur Smith on his latest, Predator (look for the huge poster on the Underground, tagline: “Let the hunt begin”), says that “Thrillers are the purest form of fiction, most directly connected to the basic forms of storytelling. The hero who keeps the tribe safe from monsters that endanger those who cannot defend themselves is THE original fictional character.” The “cynegetic paradigm” – a phrase I owe to the Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg – to do with following a scent, a trail, figuring out a puzzle, extends from nomadic hunter gatherers, through Sigmund Freud, to Conan Doyle.

The obvious precursor of the contemporary thriller is the western. The classic western is Shane, written by Jack Schaefer, who never went further west than Cleveland, Ohio. The lone cowboy rides in, annihilates a lot of bad dudes, then gets back on his horse and rides out again. Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns are a series of variations on this basic structure. The tradition of the western is not really American but imports the earlier European model of the knight errant, who may or may not be seeking the holy grail. Maybe it is no coincidence that Dan Brown’s biggest bestseller was The Da Vinci Code.

The entire canon of western literature draws on the figure of Jesus Christ, the ultimate outsider figure who renounces material goods in order to dedicate himself to a transcendent moral cause and must be sacrificed for the sake of others. In the pre-Christian “Allegory of the Cave”, first set out by Plato, a lone fugitive ventures out of the cave to discover that there is a real sun out there, and not just shadows, and returns to reveal the truth to fellow cave-dwellers only to have them assassinate him, lest his truth shatter their comforting delusion. The modern noir series prefers to save the saviour so that he can return in the next instalment, but the offer of sacrifice is there.

Paradoxically, exceptionalism, the case of the rogue individual who stands against the beliefs of the mass, is a big vote-winner. Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “noble savage” wanders through the pre-social state of nature, lonely as a cloud. He is not a team-player. He is a warrior, but he is also a drop-out, a perpetual rebel, raging against any sign of the collective. The philosophy of noir is probably best expressed, in modern times, in Jean-Paul Sartre’s existentialist one-liner, “Hell is other people”.

Sofia Helin, who stars as Saga Norén in The Bridge and is writing her own Nordic noir television series, takes the long view: “Look at the Bible, or Greek dramas like Antigone, or the Medea. They contain the same human darkness as we are struggling with today. I think humanity as a species contains darkness and we are all trying to understand it and deal with it by reading or watching and thinking. That will never change.” She adds that “I think the amount of darkness always is the same, but just comes in different shapes.”

Mark Billingham, author of the Tom Thorne series and most recently the standalone Die of Shame, summed up the contemporary genre in three (or possibly two) words: “Everyone’s fucked.” He is explicit about the politics of “alt-noir”.

“It’s a sweeping generalisation, but I’m going to say it anyway – a lot of thrillers, boys’ toys, bombs, planes etc do appeal to those on the right, and in the US, certainly, are written by those with largely Republican tendencies. There are of course many notable exceptions, the mighty Lee Child being one of them. But I do think this is a paranoid genre which speaks to those who believe there is only one way to solve a problem, which is to give someone – anyone – a damn good kicking.” He added that the Trump victory was “the dénouement that many of the sub-genre’s practitioners and most of its protagonists would have wanted.”

A note of caution comes from Gregg Hurwitz, Los Angeles-based author of Orphan X (being made into a film starring Bradley Cooper) and the imminent The Nowhere Man, who reckons that “thrillers tend to reflect rather than steer”. But he also allows that with the merging of news and entertainment “the average citizen doesn’t know how to discern what is real and what isn’t, literally and emotionally”.

By and large, the noir hero tends to avoid politics. Ian Rankin, the Scottish writer, says that his hero Rebus (a police detective, true, but one that is deeply flawed and rails against the system, coincidentally also on his 21st outing in Rather Be the Devil) “has only voted three times in his life, each time for a different party.” But then Napoleon also claimed to be above politics. To be anti-establishment. An outsider (quite literally, coming from Corsica). Rankin adds, “In an age of lies, the fiction writer is king.”

When I was in Wyoming over the summer at the Ucross Foundation, on a Norman Mailer fellowship, and working on an anti-phallocentric variation of noir, splicing Child with Camus, transposed to the frozen north, the talk was all about Trump. Trump monopolised discourse. His speeches were broadcast live across the nation. And there was something awfully familiar about his narrative. The American city had been taken over by drug dealers, rapists, killers and terrorists (he claimed). But the real criminals were in Washington. (“Lock her up!”) The political establishment. I am the outsider. I volunteer to sacrifice myself to the nation in order to save it. Messiah-style.

Back in Brexit Britain, all you had to do was replace “Washington” by “Europe”. Nationalism is only anarchic individualism, elevated to the level of the mass. Hell is still other people, but they are all foreigners and immigrants. In the most successful political narrative of our time, Washington and the European Community have become versions of Smersh or Treadstone, masters of black ops, that have to be blown open by a Bond or a Bourne. Thus sub-political figures, who would otherwise appear marginal, almost comic, are invested with the aura of militant heroes. Gunslingers.

The difference from Shane is that back then the cowboy would get back on his horse and keep on riding. Mercifully, he didn’t stick around for the next four years.

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me’ (Bantam Press, RRP £18.99). Andy Martin also teaches at Cambridge University

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments