The top 10 cultural moments of 2015: 5-7 include Kanye at Glastonbury and Saul at Glyndebourne

As we near the year’s end, we take stock of 2015 and the events, shows, scenes and performances that had a nation talking

5. Greece Lightning - Holly Williams

How delightful that the biggest theatrical trend of the year wasn’t some hip gimmick or celebrity spangle, but the oldest form of drama we have. The Greeks were everywhere, and proved capable not only of speaking sharply to our modern world and contemporary anxieties, but also of carrying innumerable interpretations and theatrical styles, from gritty realism to high-octane ritual.

There was even a micro-trend of feminist rewrites: both Marina Carr’s Hecuba at the RSC and Rachel Cusk’s Medea at the Almeida staged textual interventions, liberating these famous women from charges of child-killing barbarism. Meanwhile, at a Medea at the Gate in London, the children took centre stage, the tragedy of marital collapse and matricide seen through the tender young eyes of Medea’s boys.

The Almeida was one of the leading lights of the great Greek revival, with a whole season dedicated to the plays. Robert Icke’s Oresteia was a revelation – and pulled off the unlikely feat of transferring to the West End, a sign that British theatre is in rude health, and that there’s an appetite for clever, thoughtful work. Weirdly, there were three productions of that rarely staged trilogy on in 2015: Rory Mullarkey’s tonally wacky version played at the Globe, while Blanche Macintyre revived Ted Hughes’s translation in Manchester’s new venue, HOME.

To chorus or not to chorus? That was one of the big questions. Icke and Carr ditched them, arguing they don’t work; Cusk’s modern, metropolitan adaptation had them as a gaggle of Islington yummy-mummies, while Ivo van Hove’s austere staging of Anne Carson’s take on Antigone was double cast: the chorus also stepped into the named parts. But in Bakkhai – also at the Almeida and also translated by Carson – they went full ritual: a chorus of women chanted, yelped and sang, with a tricky a capella score by Orlando Gough.

Meanwhile, ditching the definitive article was clearly in vogue: witness also Iliad, a marathon multimedia staging of poet Christopher Logue’s take on Homer’s epic. Produced by National Theatre Wales in four two-hour chunks at the Ffwrnes in Llanelli, it was one of two radical re-imaginings of Greek myths in Wales to be heaped with critical acclaim – the other being Sherman Cymru’s Iphigenia in Splott. Gary Owen’s contemporary monologue rails against the harshness of austerity Britain, but the Greek tragedy’s theme of sacrifice is at its heart. After five-star runs in Cardiff and Edinburgh, it goes on tour in 2016 – suggesting we’re not done with the Greeks just yet.

6. A religious experience at Glyndebourne - Claudia Pritchard

When the endlessly inventive director Peter Sellars brought Handel’s oratorio Theodora into the 20th century and on to the stage in 1996, it was the first of five new-look Handel productions to date at the East Sussex opera house and on tour. The next, Rodelinda, in 1998, also made waves, thanks partly to the British operatic debut of counter-tenor Andreas Scholl. Then came Giulio Cesare (2005), and a shimmying, shimmering Danielle de Niese. With Handel’s massive output to go at, and its depth of dramatic potential finally realised, it looked as though Glyndebourne could pull it off every time, and many other companies tried to follow suit with varying success. This smooth machine faltered with an iffy Rinaldo (2011), which has improved with wear, but for the 2015 season and regional tour, Glyndebourne returned to form, not with an opera, but, as with Theodora, a staged production of an oratorio, this time Saul, directed by Barrie Kosky. With Ivor Bolton conducting the OAE, Christopher Purves in the title role, Iestyn Davies as David and Sophie Bevan (left) as Michal, Saul had a head-start, and Katrin Lea Tang’s dazzling set and Otto Pichler’s movement gave this remote Old Testament skirmish passion and point.

As David Hare’s entertaining, if at times misleading, play about the founding of the opera house, The Moderate Soprano, usefully recalled at Hampstead Theatre this autumn, it was Glyndebourne alone that in the 1930s brought high standards to a pretty pedestrian British opera scene. Productions such as Saul show that this house can still set the bar for the rest; and there are a couple of dozen more Handel titles to go at. Kosky and his team saw that it doesn’t have to be outré to stand out, something that the musically excellent but cash-strapped and benighted English National Opera - whose recent Boheme and Force of Destiny both tried too hard to shock an unshockable, seen-it-all audience - should recognise.

Simple but captivating devices in Saul, such as organist Jamie McVinnie spiralling up through the floor like a Georgian Mighty Wurlitzer, live on long after the notes have died down. Magical.

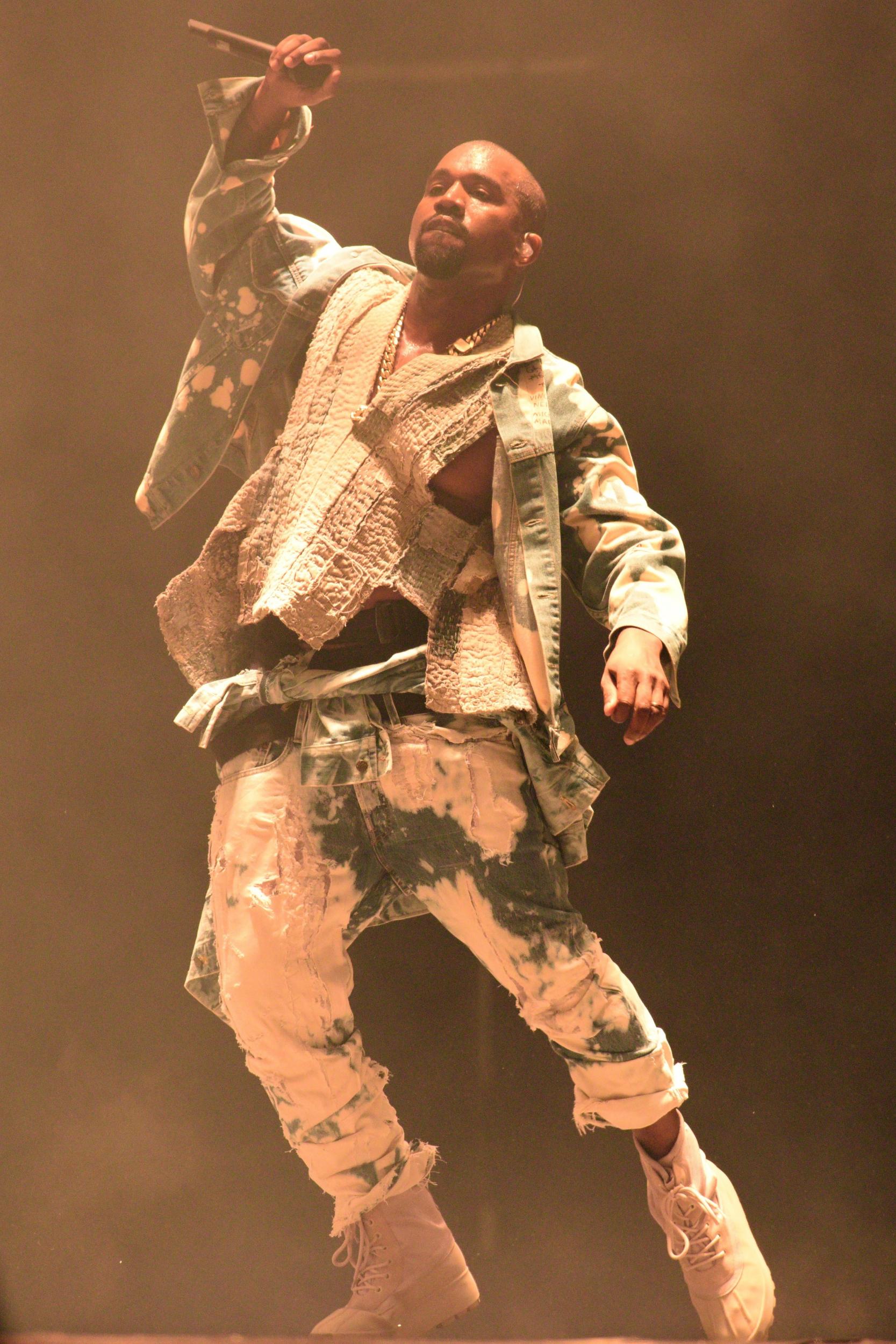

7. Kanye West at Glastonbury - Fiona Sturges

Kanye West always knew he was dealing with a potentially hostile crowd at Glastonbury. Such was the uproar at his being the Saturday headliner that a man who had never been to the festival launched an online petition to remove the rapper from the bill, and got over 130,000 signatures. Then there was the merry band of halfwits who went to the trouble of having “Fuck Kanye” T-shirts made, so they could wear them at the festival while watching safe old white dudes The Who and Paul Weller.

So, what did West do to assuage the scores of doubters during his performance? Absolutely nothing. There were no dancers, no glitter cannons, and no dazzling pyrotechnics on the Pyramid Stage. There were none of the customary shouts of “I love you Glaston-Berry’ favoured by US performers, or barked monologues of the kind dispensed by West at previous shows. Instead there was just the spectre of Kanye refusing to crack a smile and slinking about under a scarily low-slung lighting rig that made the stage look like something from Independence Day.

Some still maintain that, by virtue of his refusal to play by the rules, it was the best gig of the festival. Just as many said it was the worst. It was certainly bizarre, from the cameo from Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon, and the cover of “Bohemian Rhapsody” in which West appeared to forget the words, to the moment when West was hoisted into the air and dangled over the crowd by a crane. It was one of the most maddening, uncompromising, occasionally baffling yet weirdly compelling shows Glastonbury has ever seen.

This was not the performance of a man trying to win anyone over. Instead it revealed a star who clearly felt his presence, and his songs, should be more than enough.

West did the exact opposite to what a headliner is supposed to do and, in the process, prompted a nation of music lovers to puzzle over whether what he was doing was any good or not.

It was, at the very least, unforgettable.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments