Alicia Markova: Britain’s superstar ballerina

She danced... every night of the week and twice on Saturdays – an unknown thing nowadays

I knew nothing about Alicia Markova before volunteering to help catalogue her personal papers and belongings at Boston University’s Gotlieb Centre.

Its director, Vita Paladino, asked if I might be interested in working on a recent acquisition. I would. How about the ballet dancer Dame Alicia Markova?

My first reaction was, isn’t she Russian? I was confusing Markova with the Russian ballerina Natalia Makarova. I soon learned that many people assumed Markova was Russian.

It was Sergei Diaghilev, the founder of Ballets Russes, who changed her name.

“Who would pay to see Alicia Marks?” he had asked her. The title “Dame” should have been an instant tip-off. Markova was British and the most famous ballerina of her generation.

Markova, I soon learned, was Diaghilev’s “baby ballerina” – the youngest dancer ever to be accepted into his Ballets Russes. She had just turned 14 and was as timid as she was small.

Her tiny stature (her 2.5-sized feet were so small that insurance companies refused to insure them as “the risk was too great”) led to her becoming known as “the ballerina who lands like a snowflake”.

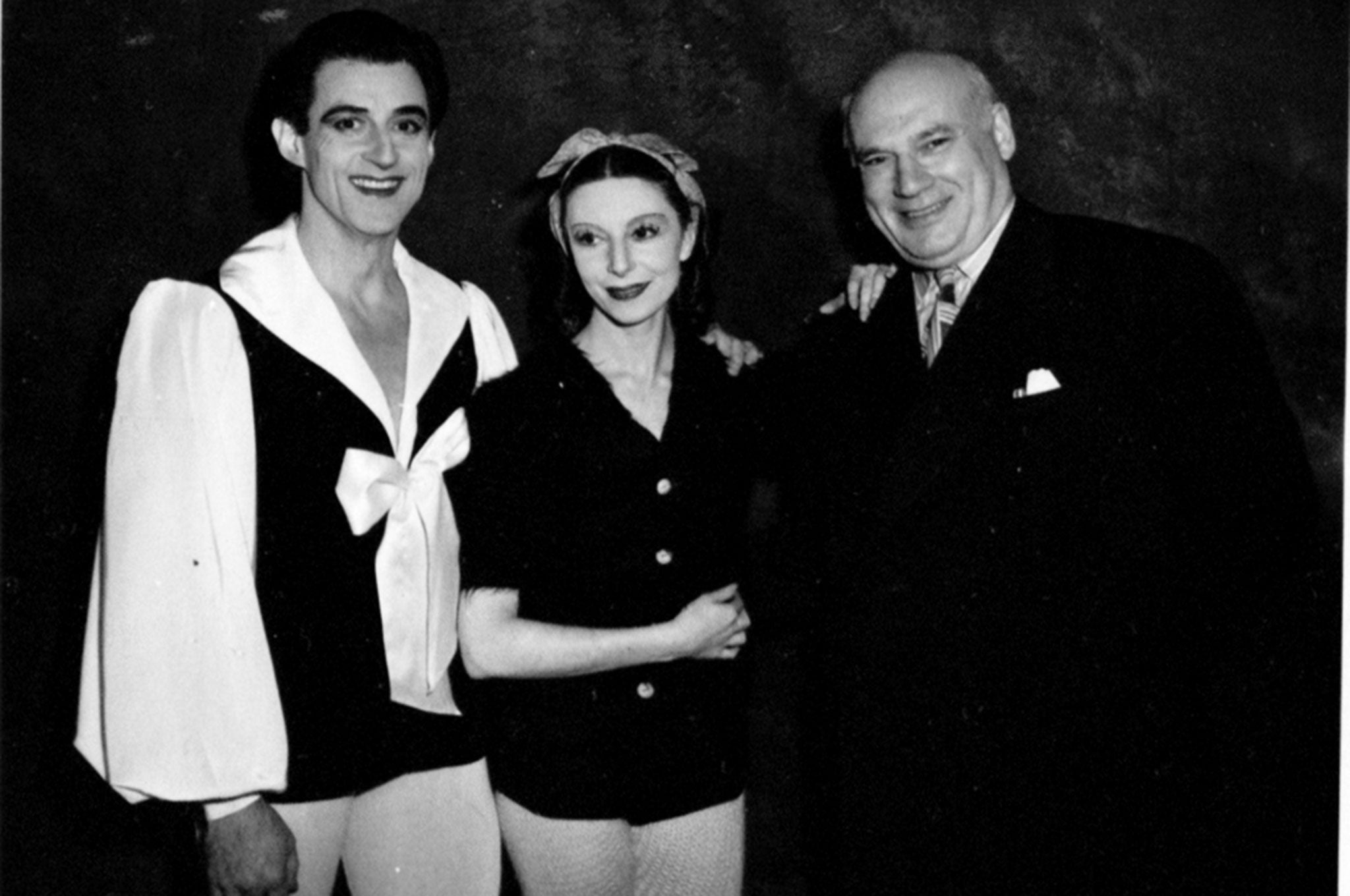

Many rare photographs and performance programmes from those times are part of the dancer’s archives. There were even rumours of an original Picasso drawing buried somewhere in the collection. (It was actually a Matisse.)

That all sounded exciting enough, but nothing prepared me for Markova’s astonishing life story laid bare in her archives. Markova, born in 1910, was a woman far ahead of her times who overcame seemingly insurmountable odds with grace, determination and an unflagging spirit of adventure.

Markova’s career is as improbable as it is remarkable. In pre-First World War England, a frail, exotic-looking Jewish girl who learnt to dance in Muswell Hill and was so shy that she barely spoke a word until age six and was so sickly she needed to be home-schooled turned herself into a superstar and became the most famous ballerina in the world.

How famous? She was asked to judge the Miss World contest held in Paris, create a “supper club” act for Las Vegas, appear with Bob Hope and Buddy Holly and the Crickets at the Palladium Theatre in London, and had her own radio programme. She was the subject of comic strips, crossword puzzles, and trading cards.

Celebrated artists asked to paint her and Vogue made her a fashion icon. She was hired as an advertising spokesperson for everything from chocolates and potatoes (yes, potatoes) to shoes and cigarettes (although she didn’t smoke). Her name alone could sell out a 30,000-seat auditorium – for ballet!

Markova appealed to both the opening-night glitterati and everyday people who had never seen ballet before her. There was even a racehorse named after her (the filly won a key race at eight-to-one odds).

Markova was a workhorse herself, devoting every waking hour to perfecting her craft. She had a hardscrabble upbringing and a zealous drive to succeed. In a radio tribute, good friend Laurence Olivier spoke of Markova’s being “nicknamed affectionately ‘The Dynamo’, –and understandably”, he explained admiringly.

“When you think she danced at least one act of a great classic ballet, and then a divertissement, and finale, every night of the week and twice on Saturdays – an unknown thing nowadays, and I’m sure would be considered impossible, because she didn’t do it just for a short season, but for a number of years.”

She not only pioneered British ballet – two of the three companies she helped launch are still in existence today (Markova became president of the English National Ballet, a company that she co-founded as the Festival Ballet back in 1951) – but she dared to go off on her own, becoming the first “free agent” ballerina and the most widely travelled dancer of her era. She performed in parts of the world that had never seen ballet at all, let alone one of its greatest practitioners.

As the London News Chronicle reported in 1955: “She is to the dance what Menuhin is to music, but unlike the violinist, she has no competitors in her field, for all the other leading ballerinas, from Fonteyn to Ulanova, work in the framework of established companies. Indeed, it seems as though Markova may be the last of her kind – the ‘rebel’ dancer who is prepared to carry the full responsibility for her career on her own delicate shoulders.”

Markova believed firmly in ballet for everyone, not just the elite. To that end, she not only performed in the world’s grandest theatres with the most prestigious ballet companies, but also in more accessible popular venues, such as music halls, school gymnasiums and even a boxing ring in Liverpool. Though she flew on stage, she was down-to-earth once off, and it made the public love her.

Several male impresarios, choreographers and dance partners didn’t share those sentiments. Markova’s fierce independence and high artistic standards drove them crazy. Many needed her name to sell tickets but bristled at giving her any personal control. Didn’t she know ballerinas were supposed to be seen and not heard? Markova was neither when it came to practising, something she always did alone.

She also never joined the company in daily classes, choosing instead to pay for private lessons. Markova wanted no distractions and this solitary endeavour gave rise to the myth that she rarely practised at all, which was far from the truth. Women in the dance world admired Markova’s fortitude, among them Dame Margot Fonteyn, who, as a ballet-school pupil in London, was completely riveted while watching Markova rehearse.

She said that Markova “always remained my ideal and my idol”. Choreographers found her skills and determination a marvel. George Balanchine, Mikhail Fokine, Frederick Ashton, Léonide Massine, Jerome Robbins, Bronislava Nijinska, and Antony Tudor all created roles specifically for Markova.

Markova had to overcome poverty, sexism, anti-Semitism, and not being considered “pretty” enough to succeed.

She was proud of her religion, which almost ended her career, and would become the world’s first openly Jewish prima ballerina assoluta – the highest (and rarest) rank of a classical female dancer. And though often urged to have her prominent nose surgically “bobbed” to conform to conventional standards of beauty, Markova steadfastly refused.

Her archive offers many clues to what motivated Markova to always push on. Certainly her personal letters are a treasure trove, but so, too, are the countless scrapbooks of press clippings. Markova was unusually open and candid with reporters and her newspaper interviews demonstrate how the timid young dancer turned into a marketing genius, managing the media and her image with an uncanny flair.

And then there is all that correspondence – boxes and boxes of it. While it was fun to read a charming note of thanks from Princess Diana or a Cecil Beaton luncheon invitation to dine with the famed fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli, it is the personal letters from the great dancers, choreographers and impresarios in Markova’s career that are the most revelatory. What a tale they tell of ego, flattery, hubris and manipulation.

The letters from Anton Dolin, Markova’s most frequent dance partner and lifelong “friend”, are positively Machiavellian.

Then there are the letters between Markova’s sisters – Doris, who served as her personal manager and travel companion for many years, and Vivienne, who shared their London apartment. Doris’s descriptions of horrendous stage conditions, unscrupulous managers and Markova’s increasing health problems are alternately disturbing and confounding. What drove the ballerina to keep up such a gruelling, self-chosen life?

Markova seemingly knew everyone. In addition to all the ballet luminaries of her time, Markova’s address books are filled with a veritable Who’s Who of the arts world, among them the performers Charlie Chaplin, Laurence Olivier, and Gene Kelly, composer Igor Stravinsky, modern artist Marc Chagall, and pianists Arthur Rubinstein and Liberace – yes, Liberace!

Markova clearly valued letters from everyday fans, especially children and soldiers, all of which she saved and personally answered. A letter from a grateful solider during the war was in the same file as a jolly note from Noel Coward. People were people to Markova.

But while Markova loved her public – she would spend hours signing autographs – she hated big parties, never getting over her shyness in a roomful of strangers. She could be great fun one moment, and severely depressed another, often retreating to her hotel room to read a book and listen to music alone. Markova herself was anything but an open book.

It is a very strange thing to read through all of someone’s private papers, even if you have permission to do so. I came across an unsigned letter in her handwriting on Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London stationery. Perhaps it was jotted down in her dressing room one evening and then tucked inside her work papers. It is uncharacteristic and heartbreaking. Though she was a superstar to the world, Markova was only human.

March 24, 1958

Dear God,

I offer you my heartfelt thanks for giving me the power & strength to live and dance through the last two years. Since Rio, I have suffered such constant pain at times it has been almost unbearable. No one will ever know how much I have suffered mentally & physically. Only due to my faith in thee and the feeling that I must try & accomplish as much as possible to help people and make them happy (as time is limited for me) has kept me going.

Thank you dear God for helping me to live a good life and one that I could be proud of. I only regret that all the truth & knowledge I have acquired in my art & otherwise will be of little use as so few people seem to want it... There is nothing here on earth to make me feel I want to stay so I am ready to leave at any time.

Alicia Markova was 47 years old when she wrote that letter – still an in-demand performer and celebrity. She danced professionally for another 4.5 years and lived to the age of 94.

‘The Making of Markova: Diaghilev’s Baby Ballerina to Groundbreaking Icon’ by Tina Sutton (Pegasus Books, £12.99) is published on 2 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments