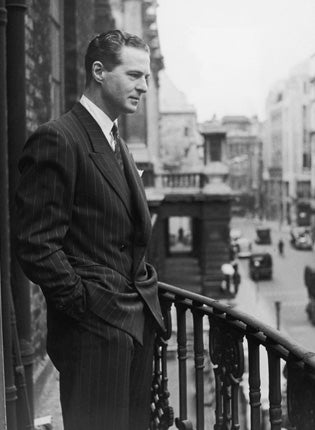

Back on stage, the forgotten Rattigan

His reputation languished after the arrival of the Angry Young Men in the 1950s. But the National Theatre's production of 'After The Dance' promises to right a theatrical wrong, says Paul Taylor

About the posthumous reputation of Terence Rattigan (1911 – 1977), three things are beyond dispute. One is that it is almost impossible to discuss his work without reference to the fact that he was the quintessential casualty of the Royal Court revolution of the mid-1950s. Pounced on by a reporter at the historic first night of Look Back in Anger in May 1956, Rattigan quipped querulously that it was as if John Osborne were proclaiming "Look Ma, I'm not Terence Rattigan". It was a catastrophic remark that would come back to haunt him, since that play's scathing diatribes against emotional inhibition heralded a new wave of theatre that would have no time for Rattigan's sensitive studies of deep-seated English reticence, unequal passion, and lonely stoicism as exemplified by his recent hits The Deep Blue Sea (1952) and Separate Tables (1954). Whatever he wrote would now be viewed through the filter of what he was perceived to represent – gilded, anachronistic privilege with his Rolls, his swanky Eaton Square address and his rounds of golf at Sunningdale.

The second is that his plays which, because of prevailing stage censorship and the criminalisation of homosexual relationships, tend to resort to the coded and the concealed, continue to arouse mixed feelings even (or perhaps particularly) among gay critics. There are those who claim that his work is evasive, internalising the homophobia of the period. There are others, such as playwright Mark Ravenhill, who contend that Rattigan's work is more truly subversive than that of the usurping Angry Young Men and that he was the principal victim of an anti-gay agenda at the Royal Court of the Fifties.

The third is that, while Rattigan has been in a state of continual come-back in recent years, his reputation still largely rests on the same few plays – those mentioned above, plus The Browning Version (1948), his devastatingly concentrated portrait of a defeated schoolteacher and the patterns of thwarted desire that surround him, and The Winslow Boy (1946), a work in which he typically uses conventional form as the Trojan horse for progressive sentiments as he explores a father's crusade against the Establishment to clear his son's name and the campaign's emotional cost.

The National Theatre, however, is making a high-profile case for the artistic supremacy of one of Rattigan's least performed plays. Apart from a moving production by Dominic Dromgoole and the Oxford Stage Company some eight years ago, After the Dance has languished in cobwebbed oblivion since its first short run in 1939. It wasn't helped initially by the change of public mood as War loomed, or subsequently by the snooty second thoughts of its author who pronounced it "turgid" and excluded it from his collected works. But there's a growing belief that After the Dance is unjustly neglected vintage Rattigan – a view shared by director Thea Sharrock whose Lyttelton revival, opening tonight, offers us a welcome opportunity to view this dramatist's career in a wider perspective. In what respects was it all of a piece? Nineteen fifty-six was a watershed, certainly, in terms of public acclaim. But what kind of response, if any, did Rattigan's plays make to the challenge of the new?

Set in Mayfair in 1938, After the Dance trains a witty but compassionate eye on the 1920s generation of Bright Young Things at a point when, no longer young or bright, they persist in partying on, their conversation nostalgically obsessed with yesteryear. The hedonism that was their attempt to obliterate the traumas of the Great War is now desperately harnessed as a bid to blank out the horrors of the forthcoming conflict. Sharrock notes that David – the wealthy alcoholic and dilettante historian – was too young, by a whisker, to fight between 1914 and 1918 and will miss the chance to redeem himself now. Salvation from his sense of pointlessness appears to arrive in the new-broom shape of puritan, purposeful young Helen, but at the grievous cost of his marriage.

Demonstrating the clear continuities between the pre- and post-1956 Rattigan oeuvre, there's a speech in his 1973 play, In Praise of Love, that could stand as the epigraph to After the Dance. "Do you know what 'Le Vice Anglais' – the English vice – really is?" asks the protagonist. "Not flagellation, not pederasty – whatever the French believe it to be. It's our refusal to admit to our emotions. We think they demean us, I suppose". This constitutional unwillingness to confront feeling was an abiding preoccupation with Rattigan. The contexts in which he explores the theme vary in their degrees of persuasiveness.

In Praise of Love was partly based on the sad case of Rex Harrison and his wife Kay Kendall. She was dying of leukaemia, a fact that both of them knew but neither admitted. But Rattigan turns the wife into a Holocaust-surviving Estonian refugee, thus giving the husband a further, contrived-sounding reason for not telling her the truth (how can he burden her with this, after the appalling brushes with death in her youth?). True, he devises an excruciating predicament for the husband who, to preserve the illusion of normality, is forced, with breaking heart, to remain fixed in his wittily insensitive and self-preoccupied persona. But Rattigan's characterisation of this Islington Bollinger-Bolshevik Sunday newspaper critic smacks of a strenuous bid to keep up with the times and is only fitfully convincing. By contrast, a similarly painful barrier to marital communication arises naturally out of the ethos the author evokes in After the Dance. Committed to the 1920s vogue of affecting to find serious emotion "boring", David and his wife Julia have concealed their affection behind a mask of studied mutual flippancy. Where, though, does this leave Julia when she's elbowed aside by straight-talking reformist zeal?

Would a little more straight-talking about homosexuality have enriched Rattigan's work? There have been recent productions of Separate Tables where the bogus Major is forgiven the disgrace of being bound over for soliciting men on the esplanade rather than groping women in cinemas and this makes much better sense of the piece. But when a more tolerant climate allowed for greater explicitness, Rattigan remained cautious and cagey. Indeed, he suffered the indignity of a rebuff from Shelagh Delaney whose portrayal of the art student in A Taste of Honey was written as a direct riposte to his treatment of homosexuality in Variations on a Theme (1958), an update of La Dame Aux Camelias. The Armand-figure here is a young ballet dancer and it's not his father but his gay mentor and choreographer, Sam Duveen, who strives to warn off the older woman.

A cross-gender tussle over the best interests of a kept boy has the makings of a meaty encounter. Disappointingly, however, Rattigan ducks the issue via Duveen's awkward insistence that his own relationship with the youth is non-sexual. "Would you try to get this into your Wolfenden-conscious mind," he tells the heroine. "Feelings sometimes can't be helped, but the expression of them can. They can and are". As a response to the Wolfenden Report, which, published the previous year, recommended the decriminalising of private consensual same-sex acts, this feels like a prim, retrograde sop to Aunt Edna, Rattigan's mythical, middlebrow play-goer.

Like many gay men of his generation, he found it hard to overcome an ingrained distrust of self and society. So a woman transgressing the boundaries imposed by age and rank for the sake of passion remains Rattigan's surrogate as taboo-breaker. This is as true of his underrated last play Cause Célèbre (1977) as it was of his masterpiece The Deep Blue Sea a quarter of a century earlier. But this swansong offers climactic proof that his gift for undermining convention from within was capable of attaining a new freedom.

It dramatises the real-life case of Alma Rattenbury, a thrice-married 38-year-old, who, in 1935, was tried with her lover, George Wood, a 17-year-old odd-job man and chauffeur, for the brutal murder of her elderly husband. Innocent of the crime but endeavouring to shield the guilty youth, she articulates Rattigan's belief that in relationships of unequal ages, it is the younger, ostensibly weaker, person who dominates.

The powerful fictional twist is that this play about double-standards equips Alma with a revealing doppelganger whose relationship to her is struck home through artful cross-fades and split screen effects. Well-bred, puritanical and repressed, Edith Davenport, the reluctant forewoman of the jurors, epitomises the misogynist society that would like to see Alma hang less for the murder than for the crime of being a life-loving, libidinous female. But then Edith begins to perceive herself as Alma's troubling reverse-image – a mother whose possessive love has begun to warp the sexual awakening of her adolescent son. In painfully destabilising Edith's preconceptions and in denying her any reward but alcoholic despair, the dramatist finally cocks his snook at Aunt Edna.

Rattigan died in 1977, deeply disappointed that the National Theatre, which had spearheaded the renaissance of Noel Coward, continued to ignore him. Next year is the centenary of his birth; he would be gratified that the NT is stealing a march on the celebrations with a revival of a rarity that should convince directors that, on both sides of those mid-career staples, there is buried gold.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments