Bugsy Malone is back: Plenty of splurge guns but no twerking teens

The Lyric theatre, Hammersmith, is reopening with a production of 'Bugsy Malone'. But, warns Alan Parker, the director of the 1976 film, child showgirls wiggling their bottoms are no longer acceptable

Backstage, the splurge guns are all lined up and the pedal car is parked in the wings. When the pedalling and splurging begin in earnest, the first major stage production of Bugsy Malone – the gangster musical that reveals the childishness of adults and the maturity of children – will be in full flow for the first time in more than 10 years.

Onstage, a rehearsal is in progress. Fat Sam's gang is about to get seriously splurged. But the ambush isn't looking quite right and Sean Holmes, artistic director of the Lyric Hammersmith, is having a brief head-in-hands moment. This is to be expected. Holmes reckons that his production of Bugsy, which will re-open the theatre after nearly two years and a redevelopment costing £20m, is the biggest show in the Lyric's 120-year history. It has a cast of 35, which is a headache in itself, but the real challenge is that the seven central characters are played by children under 16, all of whom are prevented by law from performing more than six days in a row.

"What that means is that we have three Bugsys, Blouseys, Tallulahs, Fat Sams, Fizzys, Dandy Dans and Lenas," says Holmes during a tea break. He is now looking remarkably relaxed. The stubble looks more like casual intent than the result of pressure. "So you have to do everything three times. Also, they are children and you say, 'Watch what's going on,' and they say 'Yeah, Sean, we are,' and then the third group, who have watched a scene fourteen times, get up and go left instead of right and you feel like screaming."

To those who remember the hit Alan Parker film of 1976 – and everyone who saw it remembers it – it is impossible to say or hear the names of those characters without a fond smile. Parker's idea grew from the need to keep his four young children entertained on long car journeys. So he invented stories populated by showgirls and gangsters. It was his eldest son, Alex, who wanted the characters to be children.

When Parker wrote the screenplay to what would become the first in a series of directorial hits (among them Midnight Express and Fame) the stories in the car became a pastiche of American 1930s gangster movies – a world of speakeasies and sharp-suited hoodlums for whom Paul Williams would later write 10 songs on adult themes such as love, loneliness and, with lyrics such as "I could have been anything I wanted to be…", lost opportunity, too.

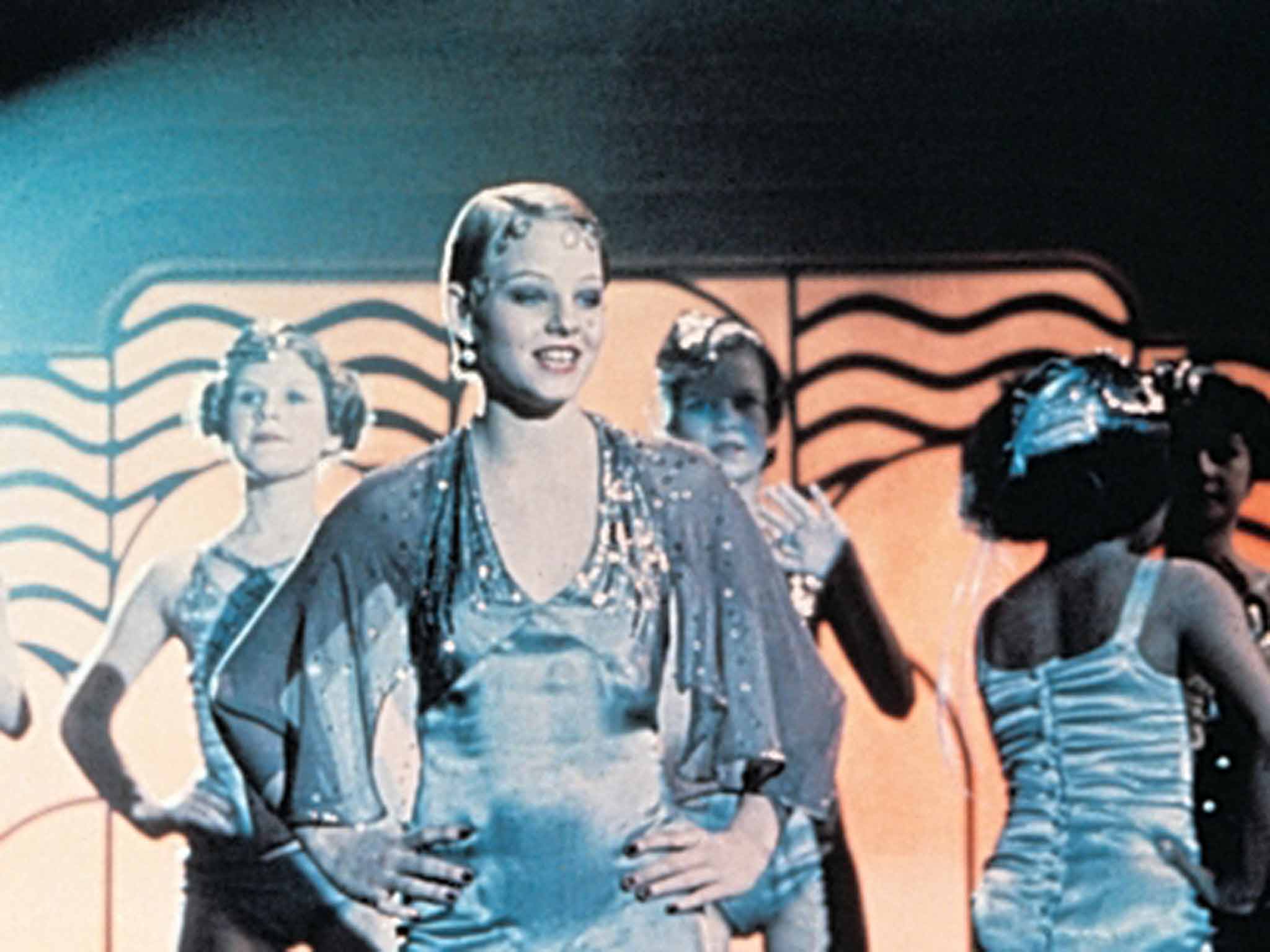

When sung with world-weary insouciance by Parker's child cast, including a 12-year-old Jodie Foster who performed "My Name is Tallulah" with all the innocence of Mae West, the songs adopted an unexpected poignancy that made adults dwell upon their own lives. Less poignantly there were also custard pie brawls and St Valentine's Day-style massacres using guns that splurged, well, splurge, instead of bullets. Nobody dies.

"I never doubted we could pull it off," says the director, now 71, speaking from a cottage in rural Suffolk, a safe distance from Hammersmith. "Although I'm sure we rushed to the Pinewood Studios bar each day, after shooting."

Parker may have had no doubts, but there were many who did. "I remember when I was doing the rounds, trying to raise money, the financiers and studios used to enthuse over the idea of an American gangster movie shot in England, but showed us the door when I said, 'Er, and all the parts will be played by children.'"

He would never agree to make a film like it again. "It's the kind of idea you only do at the beginning of a career. I wasn't brave. There was a certain naivety as it was my first film. It's a highly complex and difficult thing to make, but I didn't know it at the time. Now I'd probably avoid doing it. Over the years there have been many overtures to remake it and I always answer, probably rather pompously, 'How would you make it any better?'"

Any modern remake would have to adapt to modern attitudes. A 12-year-old child camping it up as a sexually knowing femme fatale, or rows of child showgirls suggestively wiggling their bottoms, would surely be seen as sexually exploitative. "Yes," says Parker. "Making the movie today, one might have concerns about sexual exploitation. But they were more innocent times and we didn't think of such things for a second: it was just a bunch of kids dressing up, having fun pretending to be adults."

"The Tallulah thing is tricky," Holmes agrees. "We're aware of that. It was interesting in the auditions; you had young people coming in sometimes doing things that were really uncomfortable or inappropriate."

Twerking teens?

"A little bit," he winces. "And obviously it didn't work. But then someone came to an audition, who is actually now one of our Talullahs, and she played it like she was the most important person in the room. And you go, 'Yes, of course, that's how Jodie Foster does it.'"

Foster's performance just came naturally, Parker recalls. "Jodie arrived off the plane having just shot Scorsese's Taxi Driver. She had been acting since she was three and had made a great deal more films than I had and so she probably directed me more than I directed her. She was totally different to the rest of the cast in that she was so knowledgeable and accomplished and, frankly, head and shoulders better than anyone else. Even aged 12, it was like directing an adult. All of us were in awe of her."

For Holmes, Bugsy Malone is perhaps the piece he was least likely to direct, given his recent record. This is the 46-year-old's first musical, but more relevantly the children's show is nothing at all like the experimental Secret Theatre season which has been his focus for the past two years. It is even less like his earlier, ferocious revivals of Sarah Kane's Blasted and Edward Bond's Saved, or his production of Eugene O'Neill's Desire Under the Elms which, with its scene of a baby being smothered, has one conspicuous thing in common with the Kane and Bond plays: "We used to have the 'dead baby' slot'," says Holmes of that series of "dark and difficult plays".

However, there is, he insists, a connection between Bugsy and those works. He speaks slightly evangelically about how the musical is the perfect way to acknowledge the Lyric's commitment to young people and to christen the building's brand new dance, recording and rehearsal studios. But beyond that all Holmes's recent productions evoke "a relationship with the audience that demands they engage with what is happening on stage," he says.

"And with the other things I've done, such as A Midsummer Night's Dream [with the Filter company] or the Cinderella panto I directed, I was interested in the traditional sense of tragedy and comedy that ends in collective celebration and communion. It will be the same with Bugsy Malone," he says, before acknowledging the scale of the challenge with a slightly less assured, "I hope."

'Bugsy Malone' is at the Lyric Hammersmith's new Reuben Foundation Wing, London W6, till 1 August (020 8741 6850)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments