Directors Katie Mitchell and Yael Farber on extreme violence in 'Les Blancs' and 'Cleansed'

Two upcoming plays at the National Theatre feature horrific violence. John Nathan talks to their directors about the limits of what can be seen on stage

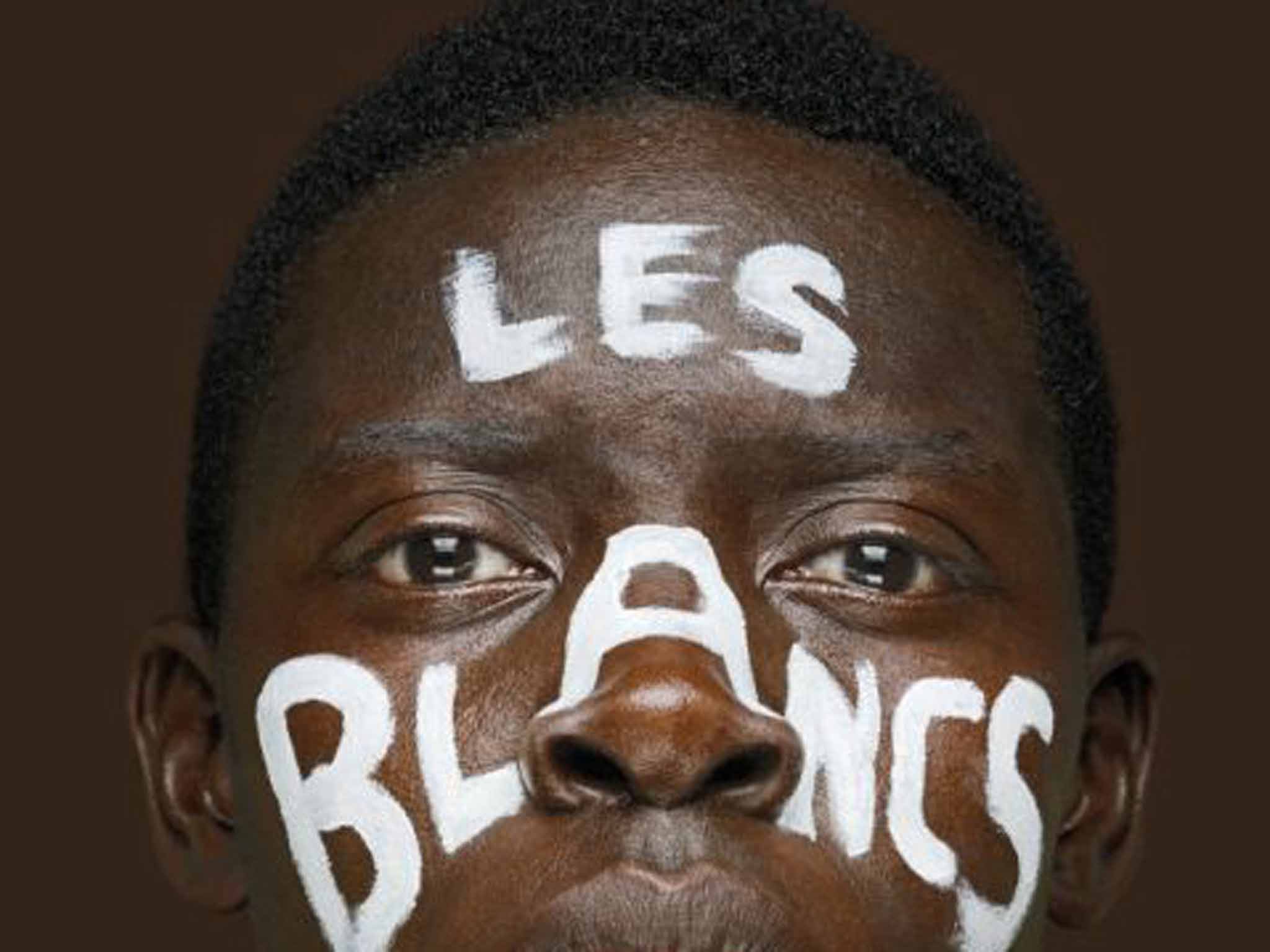

Directors Yaël Farber and Katie Mitchell have never met before. But they have a fair amount in common. Each has a play on at the National Theatre – Farber for the first time, with a revival of Lorraine Hansberry's Africa-set Les Blancs, Mitchell for the umpteenth, with Sarah Kane's ultra-violent 1998 play Cleansed.

Both directors have a reputation for fearlessly exploring their chosen territory. Apartheid figures strongly in the South African-born Farber's case, most conspicuously with her hit 2012 Strindberg adaptation Mies Julie. There was also Nirbhaya (2013), based on the Delhi bus gang rape. Mitchell, meanwhile, is for many this country's most talented director thanks to her visceral versions of the classics and her experimental “live cinema” productions. Both women are also single mothers, who have to deal with the practicalities this involves: on this particular morning car trouble has meant Mitchell has had to bring her daughter to work. And both approach one particular challenge of theatre with the same unflinching gaze: violence.

“Kane's stage directions request literal violence,” says Mitchell. “A tongue is cut off with a pair of scissors. Hands are cut off. So how do you do that in a way that is not symbolic?”

Few plays are more violent than Cleansed, in which authority is imposed in a university with extreme violence by the sadistic Tinker. Mitchell describes the terrifying amputating machines they have made for the production, and then also the crucial “moral framework” within which such acts must be depicted.

“This play is dealing with violence, tenderness and love,” she says. “You can't sanitise the moment. You have to do justice to it.”

“But it depends on what is being said,” says Farber. “Kane is saying 'this is what we do, and we are also tender creatures.' We [she and Mitchell] are both engaged in approximating an experience of what is actually involved in violence. I'm one for doing the opposite of what the Greeks did, where everything happens off stage and people talk about it.”

To that end in 2013 Farber wrote, devised and directed Nirbhaya, a play based on the horrifically real-life violent assault on a young woman by a group of men in 2012. The play was forged in Delhi, where the assault took place. It tackled head-on sex attacks by men on women.

“Many people thought I actually showed the rape,” says Farber of Nirbhaya. “But we didn't even touch what happened to Jyoti [the victim].”

“There is an intellectual thing about violence,” adds Mitchell. “And then there is the practical staging solutions that you have to deliver.”

Both directors agree there are two general approaches to violence: the symbolic and the literal. But for Mitchell: “If you do too much symbolism it makes the window to the ideas opaque.”

“Exactly,” says Farber. “It makes your directorial hand the focus. It's the opposite of the shock factor for me. It's about creating an immersive experience inside the given circumstances of a society.”

For Farber, real events demand a different approach to fictional ones. Where there is already a “cultural knowledge” of a particular event, such as the Holocaust, the “high wire” walk is in doing justice to what happened without the directing becoming a “narcissistic” presence.

“I remember once doing Phoenician Women, ages ago,” says Mitchell, casting back to her 1995 production of the Euripides play – a production that drew upon the then still-raging Bosnian war. “I was pleased – vainly pleased – with the execution of the violence. I was sitting in the theatre and the man next to me was tutting away. When I said 'what's your problem?' he said, 'I was there. It wasn't like that.' What was shocking was not only my failure but the realisation that I had to be very cautious about representing violence because you don't know who the audience is.'

“The big headline is that over 90 percent of violence is committed by men – against men, against women, against children,” she continues. “So for me violence is a gendered issue. One in four or five women have been raped. If you do a rape scene there are going to be women watching who have experienced it.”

“Yet at the same time, the witchcraft of theatre is that you have to lead an audience to believe they've seen something they haven't,” says Farber. “We [she and Mitchell] are both engaged in approximating an experience of what is actually involved in violence. You're also talking to two people who have had a certain life experience,” she adds as if increasingly aware of the parental experience she has in common with Mitchell.

“When I first had my child I would go straight into the [rehearsal] room and deal with violence. You have a high level of sensitivity when nurturing a life,” says Farber. Then, as Mitchell returns to Kane's play and the machinery of torture, her daughter appears at the door before leaving the building to go to school. Mitchell follows her out. “Can you wear your hat and gloves please?” she says.

'Cleansed', 23 February to 5 May; 'Les Blancs', 30 March to 4 May, National Theatre, London (nationaltheatre.org.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments