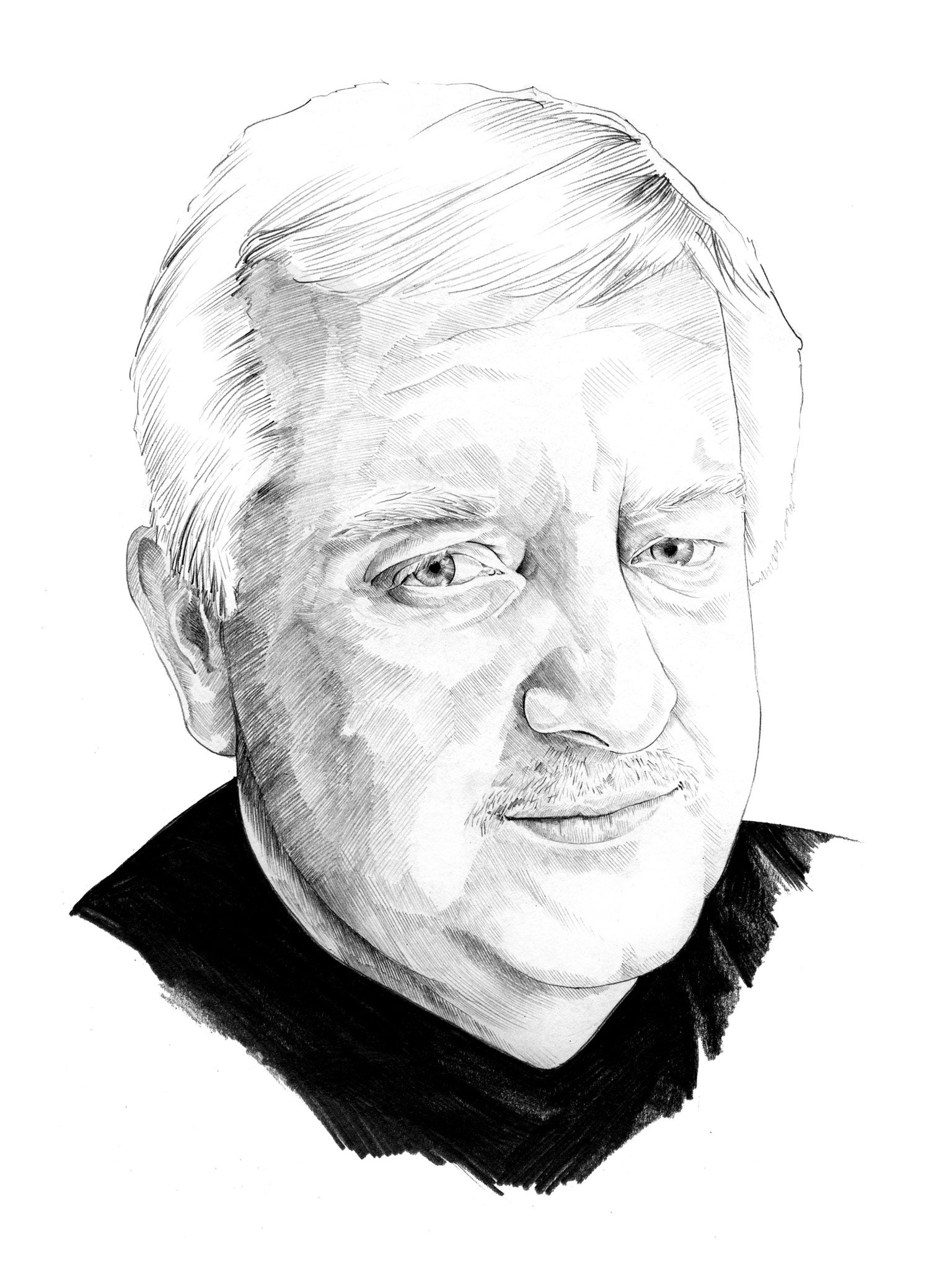

Simon Russell Beale: Best and soundest actor of his time

Simultaneously playing the ghost of Hamlet’s father and King Lear may seem an impossible feat, but it’s just one more first for Britain’s foremost stage actor

Is there no limit to his genius? The question arises with particular pertinence at the moment because Simon Russell Beale is pulling off the rare trick of appearing in two Shakespeare productions concurrently. At the New Diorama in north London, he is to be seen as the ghost of Hamlet’s father in a digitally recorded performance of brilliantly understated intensity and disgust – a spectral cameo done as a favour to Mark Leipacher, the Faction company’s artistic director, who is also writing the actor’s official biography.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Thames and far from the battlements of Elsinore, the man widely regarded as the greatest actor of his generation is mounting an assault on the role reckoned to be the Everest of the classical repertoire. Next Thursday is the press night of the National Theatre’s production of King Lear in which Beale has renewed his long creative partnership with director Sam Mendes. Their association began at the RSC in 1990 with Troilus and Cressida and his extraordinary portrayal of the Greek camp follower Thersites as a scrofulous, hate-filled stand-up comedian, suppurating with cynicism and complex, masochistic resentment.

The actor jokingly claims that he was the company’s “resident poof” back in those days, but the fat, outrageous fops that he played in a series of Restoration comedies in the late 1980s gave early notice of his matchless ability to suggest that the public persona of a character may be the painful obverse of the private self. He offered sudden, haunting glimpses of the onanistic loneliness and fear behind the peacock display of those compulsive show-offs.

Noting that Beale tended to be cast as either screaming exhibitionists or apologetic failures, Terry Hands, who then ran the RSC, shrewdly invited him to play Konstantin in Chekhov’s The Seagull, a part that enabled him to enmesh those qualities and turn the extravagant rage inward upon himself in an aching study of a dangerously vulnerable young man, desperate for his neglectful mother’s love and thus caught between compensatory delusions of grandeur and a massive inferiority complex. It was a breakthrough performance that Beale regards as a career milestone.

King Lear is the seventh Shakespeare play on which he has worked with Mendes (who has also directed him as Richard III, Ariel, Iago, Malvolio and Leontes). But it isn’t his first Lear. As a 17-year-old schoolboy, he took on the role at Clifton College, where his English master, Brian Worthington, was a friend and former student of F?R Leavis whose rigorous approach to textual analysis had an enormous influence on Peter Hall, Trevor Nunn and the emergent RSC. Beale, who graduated from Cambridge with a first in English, absorbed this tradition as an adolescent and has described acting as “three-dimensional literary criticism”. Three years ago, he gave the Ernest Jones lecture at the British Psychoanalytical Society and it teemed with arresting perceptions about Shakespeare’s characters – he argued, for example, that Macbeth murders Duncan as a “gesture of love” towards his wife to make amends for their dead child – that were the product of keen academic intelligence and his intimate involvement with them as an actor.

He comes from a close military family, his father rising to the post of surgeon-general, the senior medical officer of the British Army. They lived abroad on postings, with Beale boarding as a child chorister at St Paul’s Cathedral school. He loved the fact that for two hours a day the boys there were treated as full professionals, and this inculcated both a precocious pride in collegiate discipline and high standards and a strong self-reliance.

At one stage, he planned to write a PhD on the culture of death in Victorian England including the deaths of children in literature, and it took him some time to realise how that choice had been shaped by the loss of his younger sister Lucy, born with a hole in the heart, who died at the age of four. Personal grief profoundly informed his portrayal of Hamlet in John Caird’s National Theatre production in 2000. There had been talk for the best part of a decade of his performing the part for Sam Mendes but the project kept being postponed because of the latter’s burgeoning Hollywood career. Beale was pushing 40 when he finally made his date with destiny and his beloved mother, who had encouraged his acting career, died of cancer just before he went into rehearsal.

If he had essayed the role earlier, his Hamlet would probably have slotted into his gallery of alienated cynics. Mendes has argued that “because he feels marginalised by his looks, [Beale] always understood the psychology of Richard III and all the other characters he has played who do not think that they have been invited to the party and smart at the terrible injustice of it”.

He was aware of the unsettling precedent of Daniel Day-Lewis driven to a nervous breakdown (at the National in the mid-Eighties) by Hamlet’s encounters with the ghost and the traumatic, unresolved feelings for his own dead father they stirred. But the loss of his mother brought out a great calm in Beale’s portrayal, making him focus on Hamlet as a play about faith as well as grief. It was a performance suffused with wry wit, piercing regret for the world that might have been, and a profoundly affecting sense of spiritual illumination in the final act.

Because his Hamlet was so belated and, at 53, he is a relatively youthful Lear, the gap between the tackling of these ultimate thespian tests is, in his case, just 14 years. He has been fiendishly busy in the interim, though, on a remarkably diverse range of work – everything, in the theatre, from Shaw, Brecht, Stoppard, Pinter and Nichols to the droll schlock of Deathtrap. On screen, he was compellingly bleak as the cuckolded, mother-dominated judge in the Terence Davies adaptation of Rattigan’s The Deep Blue Sea and full of sly wit and encroaching melancholy as Falstaff for Richard Eyre in the BBC’s “Hollow Crown” season. A movie career has eluded him, however, perhaps because he’s diffident about selling himself to producers and because the American stories Mendes has tended to film don’t offer him an obvious home. (He’s hardly nature’s idea of a Chicago gangster.)

Centre stage is where he belongs. It remains to be seen how Beale negotiates the vast emotional arc of Lear. It’s a play built around the idea of exposure – to the stormy elements, to the sufferings of the most wretched, to the tempest in the mind that brings glimmers of enlightenment. This increasing nakedness of contact with the audience is likely to be especially powerful and unwithholding in Mendes’ production because of Beale’s great gift for making the conflicts within a protagonist appear to be continuous with his own. Comparing him to the protean Mark Rylance, I once invoked Dr Johnson’s distinction between Shakespeare, who becomes all his characters, and Milton, who turns everything into the struggle of being Milton. I wouldn’t want to overstate this – he is anything but a solipsist – but there’s a sense in which the spectators at the new King Lear will be watching the latest instalment in the spiritual biography of Simon Russell Beale.

Life in brief

Born Simon Russell Beale, 12 January 1961, Penang, Malaysia.

Family: Three brothers and two sisters. Parents are Lieutenant-General Sir Peter Beale and the late Julia Winter.

Education Achieved a first in English from Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, before graduating from Guildhall School of Music and Drama in 1983.

Career He made his name at the Royal Shakespeare Company as a comic actor in the 1980s. Since 1995 he has been a regular player at the National Theatre, a BBC radio and television actor and presenter. He has won two Laurence Olivier and Bafta awards and is an associate artist of the RSC, National Theatre and Almeida Theatre. In 2003, he was made a CBE for his services to the arts.

He says “I hate my body. I hate it. I hate my looks. I hate my voice. So much of what I do on stage is really saying: love me, despite the fact that I’m ugly.”

They say “Simon’s great art is that he can take a role and turn it until it catches the light. Sometimes he only turns it two degrees and bang.” Sam Mendes, director

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments