Simon Stephens on 'Funfair', the general election, and putting poverty on the stage

He won an Olivier Award for his version of 'The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time' but Simon Stephens says that his new work, set in Manchester, will mix comedy with downright rage

Odon von Horvath was 37 when he died. He was walking along the Champs Elysées in a thunderstorm when lightning struck a tree; a branch fell and hit him on the head, killing him instantly. That was in 1938. Born in Austria-Hungary, Von Horvath was living in Paris, in exile from the Nazi Party.

Von Horvath's work isn't as well known in the UK as it should be. He won the prestigious Kleist prize in 1931 and the playwright Stefan Zweig described him as "the most gifted writer of his generation". Peter Handke, who won the International Ibsen Award in 2014, wrote lovingly about Von Horvath in an essay titled "Von Horvath is better than Brecht."

I adore his plays. They are rich and redolent. I love the way his characters surprise me. He writes with detachment and wisdom about the ironies of love and hope. He lacks Brecht's didacticism and seems more driven to capture the mess and uncertainty of being alive than to articulate a persuasive ideological idea. His characters contradict themselves and their language counterpoints their situations in a way that reminds me of Chekhov more than any other writer. That counterpoint and contradiction is something I always aspire to in my own work. There is a juxtaposition between his characters' capacity for desire and their stasis that seems to evoke Beckett two decades before Beckett wrote for the theatre.

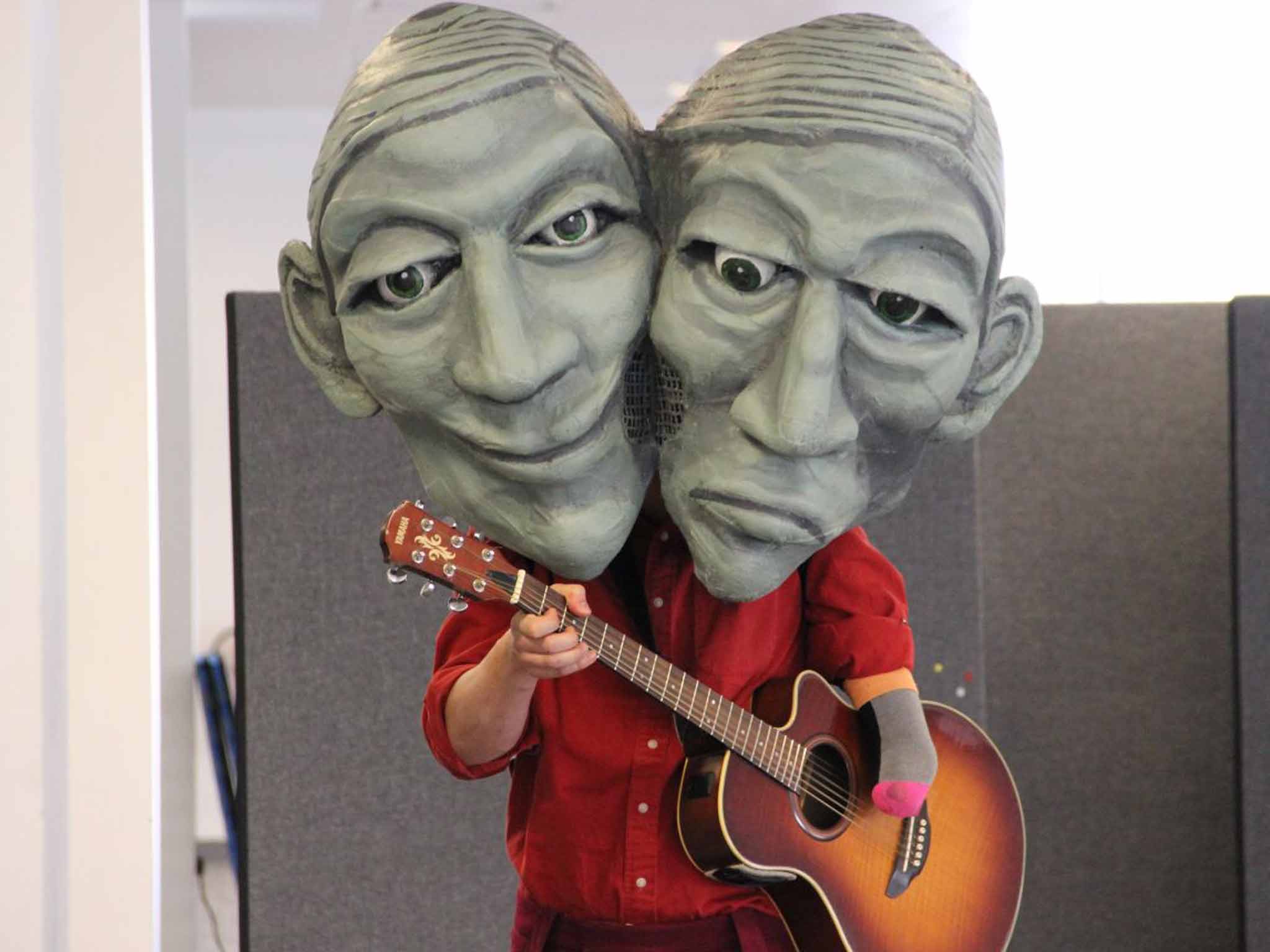

Last year I wrote a new English-language version of his 1932 play Kasimir und Karoline. It is a romantic and dirty play about a young couple who break up in a fairground over the course of one night. Kasimir (Cash in my version) has just lost his job as a chauffeur. Karoline (whom I re-christen with a "C") has a hunger that he can no longer satisfy to explore the edges of her world. The original play was set in the Munich Beer Festival at the end of the 1920s, but I have relocated it to contemporary Manchester and renamed it The Funfair. I am honoured that it will be the opening play at Manchester's new Home Theatre.

It seems appropriate to open a new theatre in the city of my birth with a play that attempts to make sense of that city. I love the idea that, in my version, Von Horvath's constellation of characters will be telling their stories a stone's throw away from the site of the Hacienda nightclub, which I often went to when I was their age. Indeed, Von Horvath seems to predict many of Manchester's dramatic literary traditions. There is a compassion for the poor and a celebration of their capacity for poetry and wonder in the play that is more likely to be found in the works of Shelagh Delaney or Jim Cartwright or Alistair McDowall than in Brecht. That tension – between a flinty examination of the lives of the skint, the drunk and the disenfranchised, and a faith in their capacity to reach for the poetic – seems to run like a vein through much of Manchester's culture.

I wanted to write The Funfair because Von Horvath's play speaks so startlingly about Britain now. It may have been set in 1920s Munich, but I know of few other plays that so directly dramatise what it feels like to be alive today. And by today I don't mean "these days". I mean today. I am writing this the morning after the most catastrophic general election for social democracy in this country for almost 25 years. Defying the pollsters, David Cameron's Conservative Party has returned to government with a majority and an increased mandate. Ed Miliband's Labour Party was destroyed by a rising nationalism, both south and north of the Scottish border.

Von Horvath was writing about precisely such a moment and precisely such a phenomenon. Reeling in the wake of the Wall Street Crash, Germany was increasingly divided between the very rich and the poor. Its working class, caught in the grip of poverty and injustice, chose not to work together for the sake of equality and justice, but to move unapologetically to the right. It was a shift that within 10 years gave rise to the brutality of Kristallnacht, the horrors of the death camps and a continent torn asunder by unthinkable war.

This move to the right by the disenfranchised and the disempowered was precisely what we saw in last week's general election. Since the crash of 2008 we have witnessed a startling increase in the disparity between the affluent and the impoverished in this country. The banks that caused the economic catastrophe of the last decade soon reverted to their bonus cultures and to nauseating increases in executive pay. In so doing they were protected by a government with the interests of such a banking culture deep in its metabolism. At the same time, the growing dependence on food banks reflected genuine poverty and despair.

What became clear last week was that this poverty and despair is manifesting itself in a move towards nationalism – a policy born out of hostility and exclusivity, and defined by suspicion and a sense of rage. This is as true in Scotland as it is in England, and it is what decimated the Labour Party last week. It is also what Von Horvath was writing about in his play.

It's the poverty and despair expressed in the yearnings of his characters, who are rendered inarticulate. It is seen in their desire to get drunk and get laid and fall in love and escape from their lives. It is evident in the comedy of a culture smashed together for one night under the shadows of the roller coasters and the freak show and the passing airship. It is also manifest in the characters' sense of rage – and this rage pushes them to the right.

I wanted to write a play about this shift. I wanted to write about Ukip and its craven, vicious manipulation of the disenfranchised and disempowered. I wanted to write about the smug hypocrisy of Cameron, Osborne and Johnson as they deregulate the companies owned by their classmates, cheered on by the editors who drank with them in the Bullingdon Club. I wanted to write about the Britain that tore itself apart at the polling booths as it voted out of suspicion rather than hope.

I realised, as I made my version of Von Horvath's beautiful play, that this is precisely what he had done 70 years earlier.

'The Funfair' runs from tomorrow till 13 June at Home, Manchester (homemcr.org/production/the-funfair)

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies