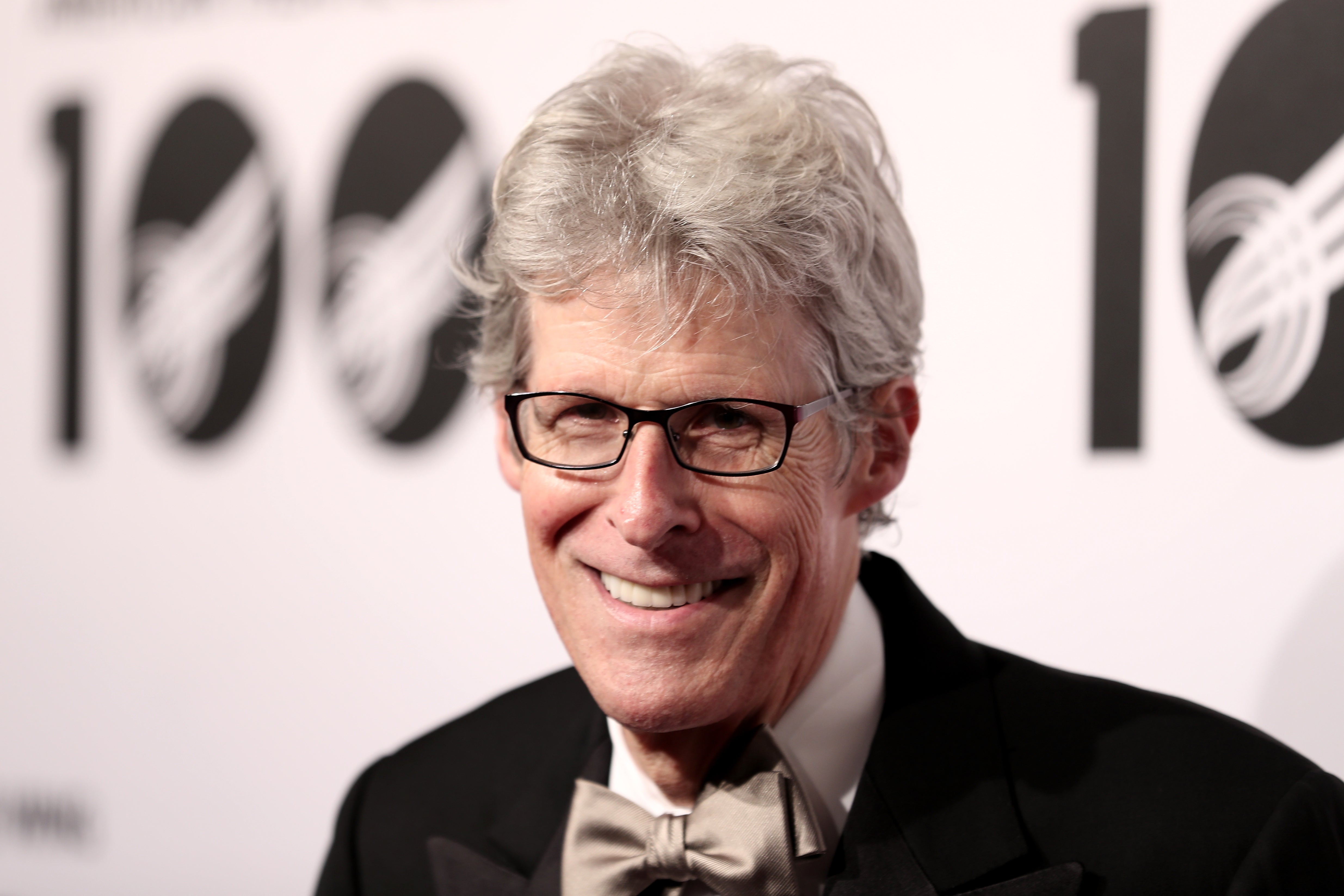

Ted Chapin: ‘Every time I see one of these shows, I discover something new’

For 40 years, he was the man overseeing Rodgers and Hammerstein’s theatre properties including ‘The Sound of Music’ and ‘Carousel!’ After finally stepping down from the role, Ted Chapin spoke to Jesse Green about his career and the future of musical theatre

In 1981, two years after the death of Richard Rodgers and 21 years after the death of Oscar Hammerstein II, Ted Chapin got a call from Rodgers’ daughter Mary, asking if he’d like to run the Rodgers & Hammerstein office.

That’s all “R&H,” as it has always been called, amounted to then: the place where the work of managing the pair’s many musical theatre properties was conducted. But in the 40 years since, it would become much more, as the office turned into an “organisation” and the business of exploiting copyrights by making new shoes from old leather changed drastically.

Chapin, 70, recently stepped down from the job he started when he was just 30 and so untried that his first two years were probational. He had been hired partly because the Rodgers were friends of his parents: Elizabeth Steinway, of the piano family, and the arts administrator Schuyler Chapin. It didn’t hurt that, while in college, he was a production assistant on Follies – an experience he would later mine in writing the classic backstage memoir Everything Was Possible. According to Mary Rodgers, he also had at least one other asset: great hair.

He still has it – and, miraculously, the R&H catalogue, unequalled in the American theatre, is likewise undiminished. But as new ways of making money from The Sound of Music and the rest presented themselves, the job of advising the heirs and maintaining their income became much bigger. It was no longer simply a matter of giving (or withholding) approval for major new productions but also a strategic puzzle: How do you uphold an artistic legacy while exploiting technology, adjusting to a changing theatrical environment and serving progressively larger corporations?

On 21 May, Chapin stepped down as president of the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organisation. We spoke by Zoom a few days later as he sized up his tenure and considered the future. Here are edited excerpts from our conversation.

Q: What was the R&H office doing when you got there?

A: It was all about major productions. Yul Brynner was out minting money on the road in a tacky production of The King and I, but the rest of the rights – music publishing, film, television – we didn’t yet handle. Later I would bring them under the R&H umbrella.

Q: Was that just a money move?

A: Not just. The more we were actually in control, the more we could coordinate things. If there was a major production of The Sound of Music coming, for example, it was better not to license one of the songs for a soup commercial. You could wait until later for that. The trick was to juggle everything, keeping it all going so they wouldn’t crash into each other. Luckily, there would always be one project on the way up while another was on the way down.

Q: Why didn’t the estates of all the Golden Age writers accomplish that?

A: Owning the underlying rights was key. When Oklahoma! became an incredible success in 1943, and Carousel in 1945, Rodgers and Hammerstein decided to produce their own Broadway shows going forward, then the tours, then even the London productions. From the time they bought back the rights to Oklahoma! and Carousel in 1953 — Oklahoma! alone cost them $851,000 — they had complete control. No other musical theatre catalogues were organised that way, so no other heirs could exploit their inherited work as successfully.

Q: And few had so many moneymakers to work with.

A: Think about what it means that, give or take, they opened a new show on Broadway every other year from 1943 to 1959. They liked to create musicals, and they were consistently pretty good at it. When they tried their hands at a television musical in 1957, they were pretty good at that, too. Cinderella is the only television musical of that era that is still a viable property today. You don’t hear much about Cole Porter’s Aladdin.

Q: And now Cinderella is a stage musical, too, joining the catalogue along with some other latter-day concoctions.

A: Yes. The original tranche included the nine stage musicals plus an earlier adaptation of Cinderella. We added the stage version of the movie State Fair, the revue A Grand Night for Singing, and the modern Cinderella. We also control the Rodgers and Hart shows, like Pal Joey and The Boys From Syracuse, and Rodgers’ post-Hammerstein work.

Q: But when you started, most of what you represented was getting dusty, and the commercial theatre environment was collapsing.

A: Broadway was definitely in an identity crisis in the early 1980s. Yul Brynner doing his hundredth tour of The King and I might make money, but it seemed that replicas of Golden Age musical comedies with Golden Age stars were not the way ahead. Early on, I went to see an off-Broadway production of Carousel, and I thought: This is the show that might help people rediscover what these works really are, because it’s dramatic in a way that musical comedies weren’t.

Q: In the years since Rodgers’ death, the office permitted 17 “first-class” productions of the pair’s musicals – 12 on Broadway and five in London’s West End. Please choose a home run, a heartbreaker and a stinker.

A: South Pacific at Lincoln Center in 2008 is the home run, for the simple reason that it was produced like a discovery: honouring what’s there but making it new. Among the disappointments was State Fair, which was created for the stock and amateur market and was never intended to come to Broadway.

Q: But it did, alas, in 1996. And then, in 2002, another disaster.

A: The revival of Flower Drum Song was a heartbreaker.

Q: Flower Drum Song is a musical with a fine 20th-century score but a big 21st-century problem: It’s about Chinese Americans as imagined by white Americans. For the 2002 production, the playwright David Henry Hwang massively reimagined it.

A: Yes. Everyone went into it with such a great collaborative spirit but ultimately it became clear that the score no longer fit what had become a completely different show.

Q: You’ve neglected to mention a stinker.

A: The Boys From Syracuse at Roundabout Theater Company in 2002. And another we pulled the plug on: Rudolf Nureyev in a misguided pre-Broadway tour of The King and I in 1989. What is the one thing the King’s not supposed to be able to do? Dance. And what was the only thing Nureyev could actually do? Dance. When I went to a rehearsal and saw him in his green jumpsuit and green crocs, I thought, That’s Our Hitler!

Q: Even aside from Flower Drum Song, will the Rodgers and Hammerstein shows survive a more critical look at the racism, sexism and appropriation some people find in classic musicals?

A: Neither man had a racist bone in his body, but it’s tricky. Hammerstein wrote in dialect so people wouldn’t sound like they were in My Fair Lady; he wanted Bloody Mary in South Pacific to talk like a woman who learned English from sailors. But to some ears now, it sounds racist. And then there’s the domestic violence in Carousel. At the moment, the most difficult one is The King and I, which forces you to ask: Whose story is being told and by whom?

Q: You and the families have been open to experimentation, often permitting directors to explore those very issues even though purists get offended. What’s your philosophy?

A: You have to have confidence in what these properties are. Rethinking them for a moment doesn’t change them forever. In the past 10 years we’ve had the dark Oklahoma! directed by Daniel Fish but also the multiracial one Molly Smith did at the Arena Stage, the all-Black one in Portland and Denver and the re-gendered one Bill Rauch did at Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Every time I see one of these shows, I discover something new. And if not, no harm. The originals are still there.

Q: Even so, their earning potential must be diminishing.

A: The business has been very consistent through all my years, no huge ups but no huge downs. That’s partly their staying factor and partly new technology. When home video came in, bingo, a musical like The Sound of Music was catnip because people wanted to see it over and over. So we licensed a double videocassette, then a single videocassette, then a DVD, then an improved DVD, then an enhanced DVD, then a Blu-ray and then as part of a collection of six R&H movies in a carousel of DVDs — and it sold every time.

Q: But the copyrights on the shows will start to expire in 2038 — which is just 17 years away. That’s a big part of why the families, soon after the market crashed in 2008, sold the R&H catalog, and the business that managed it, to the Dutch company Imagem, for a reported $225 million. Did they make the right decision?

A: Not knowing at the time how fractured the next generation could have become — there are something like 20 grandchildren — yes. And it was smart to keep the rights and the management of the rights in one place. But they could have gotten more.

Q: In 2017, as part of a trend of consolidation in the music business, Imagem was bought by the music giant Concord, which thus became your boss. Why leave now when you’ve got such a big player behind you?

A: Concord does like buying things — they’re very good at that. But when I started, R&H was a family business; we knew what we were doing and we had a good time. Once it became part of a company that’s a company company instead of a theatrical office, that changed. I’m not leaving with any animosity, but it was time to make a graceful exit.

Q: Will you write a tell-all?

A: I hope so. I’ve got the title, anyway. When I attended the first preview of Carousel in London in 1992, a woman seated next to me in the box smiled and asked in a posh accent, “Are you with the production?” Which seemed to sum up this strange job I’ve had, sort of in and sort of out. Only later did I realise it was Princess Margaret.

© The New York Times

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies