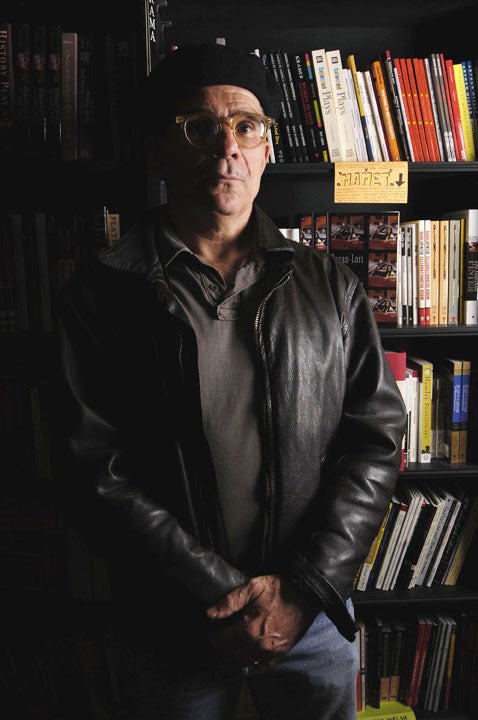

The enigma of David Mamet

David Mamet's latest play has been panned in New York. But a UK revival of Speed-the-Plow, starring Kevin Spacey and Jeff Goldblum, reminds us of his astonishing powers, says Paul Taylor

David Mamet, whose 1988 Hollywood huckster play Speed-the-Plow has opened at the Old Vic in a revival starring Kevin Spacey and Jeff Goldblum, has just had a bruising run-in with the New York reviewers. Arguably the greatest and most influential of living American dramatists, he has been confronted with the fact that his latest theatrical venture, November – in which Nathan Lane (of The Producers fame) plays an unpopular President seeking re-election – has, with a few murmurs of mitigation, been panned.

Having read the script, I can say that the critics have not been unduly cruel. In his review of the Broadway premiere, The New York Times's Ben Brantley argued that "November is a David Mamet play for people who don't like David Mamet". It's scattergun satire about a jovially corrupt, torture-condoning President abandoned by his unnamed party. It involves a scam arising from the annual White House pardoning of the Thanksgiving turkey, a pork-industry funded "piggy plane" for the extradition of dissidents and dud exchanges like this one (between lawyer and President) – "We can't build the fence to keep out the illegal immigrants." "Why not?" "You need the illegal immigrants to build the fence."

As a progress report on the career of this celebrated 60-year-old Chicago-born playwright, film-maker, novelist, essayist and polemicist, the notices make gloomy reading. The general verdict is that Mamet's distinctive talents are conspicuous here by their absence. For once, his timing is off. He has hitherto had the knack of seizing (and sometimes anticipating) the zeitgeist. Take Wag the Dog, the 1997 movie that he co-scripted, in which spin doctors distract the public's attention from a presidential sex scandal via a virtual war with Albania. Less than a month after the film was released, Clinton was entangled in the Lewinsky affair. The only difference was that, in the fictional version, the war footage was faked by a Hollywood director. Not so the missile strikes against Sudan and Afghanistan.

Likewise, with the fatal confrontation between a professor and a female student (leading to harassment charges and eventually violence) in his 1992 play Oleanna, Mamet pitched into the subject of political correctness and its pernicious effects on campus while the subject was still white hot – long before novelists JM Coetzee and Philip Roth got round to it in, respectively, Disgrace (1999) and The Human Stain (2000). By contrast, November, in Brantley's verdict, "might have been an act of daring four years ago, when Mr Bush was running for a second term. But in the twilight of his executive tenure, the American presidency has become a fish in a barrel for everybody's target practice."

More disappointing still, the unmistakable Mamet voice is heard only fitfully and with strain. True, one reviewer counted 167 instances of the "F-word" – the dramatist's predilection for this profanity being now the stuff of legend – and of gags such as the one about the toff who, on his way into a theatre, sees a beggar and sniffily tells him: "Neither a borrower nor a lender be – William Shakespeare"; to which the bum replies: "Yeah. Fuck you – David Mamet." But a fistful of "fucks" is meaningless without the hallmark Mamet rhythms – staccato street jargon raised to the level of stylised concrete poetry, full of overlappings, ellipses, backtrackings, dislocated repetitions – at once in-yer-face and circumspect, with emotional undercurrents of brutality and fear.

Born in 1947, Mamet was the son of a labour lawyer and the product of a painfully broken home. He has said: "In my family, in the days prior to television, we liked to while away the evenings by making ourselves miserable, solely based on our ability to speak the language viciously." This fraught domestic atmosphere tormented his heart but trained his ear.

The resulting dialogue is not to everyone's taste. One critic has disparagingly parodied the playwright's characteristic tics: "Well, hell, look at it: um, um Mametspeak, I mean, it's, it's ... there to, to – what's the word? To reveal... conceal the ... um ... What? ... meaning." But to most ears, the dramatist's meticulous, musically notated dialogue is a deeply imaginative elaboration of the manner he inherited from Harold Pinter. Pinter, the dedicatee of one of Mamet's masterpieces, Glengarry Glen Ross (1983), directed the debut UK production, a decade later, of Oleanna.

The uncanny exactitude of Mamet's notation is borne out by a story told by the actors David Suchet and Lia Williams, who played the professor and the student in that production. At the start of rehearsals, they found the carefully positioned emphases inhibiting. So Pinter asked the author for a script without the underscoring. Mamet declined on the grounds that the stressings were all in the right place and necessary. Pinter stuck to his guns and an unmarked script was provided. The telling point is that when the actors re-consulted the marked script four weeks into rehearsal, they discovered that they were in fact playing virtually every emphasis originally indicated there.

The versatility in application of the mesmeric Mamet rhythms is, however, often overlooked. They can register the foul-mouthed, fast-talking macho bluster and flirty sales patter of the driven real-estate men in Glengarry Glen Ross (the salesman, for Mamet, is as symbolic a figure in the exploded myth of the American dream as he was for Arthur Miller). But they can also communicate the more sensitive and hesitant groping for connection between, say, the betrayed 1950s wife and her gay male friend in The Cryptogram (1994) and the clipped, awkward attempts to move beyond cautious cliché into belated intimacy in the exquisitely calibrated father-daughter Reunion (1976).

A peculiar situation has arisen, though, in the arc of Mamet's career. There are the later works, such as Boston Marriage (2001), a mock-Jamesian comedy about lesbians in a scam over an emerald necklace – which has the air of the public settling of a private bet, with Mamet chomping on a cigar and thundering: "Who says I can't do women? I can do women. I can do women squared. I can do dykes!" – and Romance, a zany, overblown sketch and courtroom farce, set against the backdrop of V C Middle East peace talks, making the crude and contentious point that Americans need to find peace at home first.

At the same time as these pieces, gag-happy and revelling in political incorrectness, are failing to find favour, a slew of excellent productions of the earlier work (such as the recent superb revivals of The Cryptogram at the Donmar and Glengarry Glen Ross at the Apollo) is suggesting that the plays are even richer and more intriguing in the balance of their sympathies than was originally supposed. With a catholic taste for this author that embraces all the various categories, Patrick Marber is also a seasoned Mamet-hand across the board of theatrical practice. As a dramatist, he has benefited from Mamet's creative influence, as can be discerned in Dealer's Choice (currently playing at the Trafalgar Studios in a brilliantly funny and painful revival) with its men-only environment, its use of poker's strategies of bluff and counter-bluff as a paradigm of male power-relationships, and its insight into a damaged father-son relationship; and in Closer, with its dissection of desire, jealousy and loneliness, like a ruthless Nineties London variant on Mamet's Sexual Perversity in Chicago. As a director, Marber mounted the beautifully judged UK premiere (at the Royal Court) of The Old Neighbourhood, a trio of linked (autobiographical) dialogues in which the playwright's alter ego returns home in search of his roots. And as an actor, he starred as Charlie Fox, the independent film producer who is one of the two buddies in an earlier (2000) West End revival of Speed-the-Plow, directed by Peter Gill.

Marber first encountered Mamet's work as a very young man when he went to see the 1983 premiere of Glengarry Glen Ross at the National. He was bowled over by "the precision of the language and the energy of the writing. I didn't understand the plot. I was 19 at the time and I wasn't interested in real estate, as I didn't own any property nor ever imagined that I would. But I was spellbound by the acting and the power it generated. Over the years, I've come more and more to admire his aesthetic, which is one of pure theatre. He has absolute faith in an audience's ability to absorb vast amounts of information very quickly."

Marber also brings up Mamet's studiedly provocative and revolutionary book True and False: Heresy and Common Sense for the Actor, in which he pours especially poisonous scorn on Stanislavsky and his revered Method with its talk of "emotional memory", substitution and "sense memory", and its emphasis on how the actor feels inside. For Mamet, this and nearly everything taught in acting schools is "hogwash". "The actor's job," he declares, "is solely to communicate the play to the audience... The actor does not need to 'become' the character. The phrase has no meaning. There is no character. There are only lines upon a page. [When these are said simply] the audience sees an illusion of character upon the stage... the actor has to undergo nothing whatsoever."

Recalling his adventures on Speed-the-Plow, Marber is ruefully funny about the pickle he initially got into attempting (as an inexperienced actor) to play it by the Mamet book. True to the playwright's philosophy, "Peter [Gill] conducted us almost with a baton in his hand and he made me go over and over the lines in an effort to approximate the musical notation. And I remember very clearly the first preview at Oxford Playhouse, walking on stage and delivering those lines and having no idea why I was saying them." He had to switch tack sharpish and create a character.

Nonetheless, he loves True and False, with its emphasis on (in Mamet's words) "the outward-directed actor, who behaves with no regard to his personal state, but with all regard for the responses of his antagonists" as a liberating corrective to the kind of self-regard that tempt some actors to say: "I don't think that my character would say or do that," rather than investigate why the dramatist has decreed things the way he has.

Matthew Warchus, the director of the new revival of Speed-the-Plow, was also soon disabused of the notion that mounting a Mamet play was mainly a matter of conducting the music of the dialogue. He likens the experience to directing Beckett's Endgame (with Michael Gambon and Lee Evans): "You can't get through half a page without wanting to explore what motivates these characters. You have to emulate the emotion that was the original source of the lines."

His production looks set to be further proof that we have underestimated the earlier Mamet. Goldblum takes the role of Bobby Gould, newly appointed head of production at a Hollywood studio. His old friend, Charlie Fox, an independent producer (portrayed by Spacey, who played one of the salesmen in the film version of Glengarry Glen Ross) brings him a sure-fire script that is (wheels within wheels) a prison buddy movie. Warchus talks of the "puppy dog quality" of Spacey's Charlie contrasted with "the lithe, jazzy, playful and zig-zagging quality" of Goldblum's Bobby. Given the calibre of these performers, the edgy, quasi-vaudevillian joshing of the pair, with its undertow of insecurity, anger and envy, should be one of the acting highlights of the year.

However, the pivotal piece of casting in this three-hander is the part of Karen, the temporary secretary who threatens to drive a wedge between the men when she not only beds Gould but causes him to question his values. She makes a rival bid to persuade him to rat on the deal with Charlie and green-light a movie based on a spiritual, apocalyptic book by an "East Coast sissy". The role has had a colourful history. In the New York premiere in 1988, Karen was played by a lacklustre Madonna, whose presence, while earning Speed-the-Plow a record advance for a straight play, was in blatant contradiction of its values. Madonna was a blank, where what is called for is an enigma. As Marber notes, it requires an actress who can make you believe in Karen's belief in the pretentious-sounding book and keep you guessing about the balance between idealism and careerism in her come-on. In addition to the tussle between art and commerce, Warchus identifies "a kind of collision between love and fear" in the drama. Gill agrees: "I think [the play] is less about Hollywood than the fear of a certain kind of puritanism... the men's vulnerability is the main theme."

This need not give offence to feminists if Karen's position is granted its full, partly inscrutable power. The play is richer for a penumbra of mystery. Warchus has cast Laura Michelle Kelly, whose CV (the first Mary Poppins in Richard Eyre's stage version; the first Galadriel, Elven queen, in Warchus's Lord of the Rings) may not strike everyone as obvious preparation for a Mamet play. But, as Marber points out, her portrayal of the magical super-nanny was "very sexy and interesting and not fully of this world". Indeed, there's a spiritual, religious-believer charge to her performances that should complicate and intensify the chemistry in Speed-the-Plow.

It's with respect to the female roles that recent Mamet revivals have proved to be salutary revaluations. In Josie Rourke's meticulous revival of The Cryptogram at the Donmar Warehouse, Kim Cattrall beautifully communicated the strain of being a perfectly groomed, model Fifties housewife. You could feel the social pressures that eventually erupted through the dam, driving her to divert her rage against her unfaithful husband on to men in general, and in particular, her sensitive, defenceless 10-year-old son.

Likewise, whereas the first productions of Oleanna incited sophisticated punters to cries of "Kill the bitch", revivals have revealed the extent to which it is a tragedy of two people caught up in the failure of modern university education. As the late philosopher Bernard Williams argued in his book Truth and Truthfulness, the play shows how the system short-changes the female student, because instead of exercising intellectual authority and properly directing her studies, the professor has only a relationship of power (partly gender-power) over her, generating the resentments that will become warped and venomous.

One would have hoped that Mamet would find these revivals inspiring, an encouragement to push further into the terse, concentrated tragic/tragicomic mode at which he excels. He has opted, rather, for broad (if barbed) jeux d'esprit such as Romance and November. Just as, in her day, Mrs Thatcher brought out the worst (of snobbery and peevishness) in certain British playwrights, so Bush seems to have oddly infantilised the gestures of protest made by key American dramatists such as Mamet and Sam Shepard – with the awkward result that a new piece like November is castigated for being "a David Mamet play for people who don't like David Mamet" in a period when powerful reappraisals of his finest work are convincing people who love Mamet that they may have underrated him the first time round.

'Speed-the-Plow' is at the Old Vic, London SE1 (0870 060 6628) to 26 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks