The Revenger's Tragedy: The bloody classic is given a modern twist

Two stage revivals of the horror-comedy open this week

Joe Orton used two lines from The Revenger's Tragedy as the epigraph to What the Butler Saw – "Surely we are all mad people, and they/ Whom we think are, are not". It's easy to see why he liked the horror-comic Jacobean vision of moral anarchy, with its depraved Italian court, its dysfunctional ruling family, its extremes of virtue and vice, and its tone of sardonic fascination. In Loot, Orton turns a funeral into blasphemous slapstick, with the corpse dumped from the coffin to make room for stolen money and then subjected to all manner of desecration, including being passed off as a tailor's dummy. In The Revenger's Tragedy, dead bodies are ignominiously bundled into bamboozling disguises and the sex-mad old Duke is tricked into kissing the poisoned skull, dolled up to look like a bashful virgin, of the woman he murdered. The big difference is that the deeply ambivalent Jacobean play looks back in its disgust to the medieval morality tradition, as well as forward in its detached relish to modern black comedy; but the temperamental affinities with writers like Orton can't be ignored.

It's perhaps no accident, either, that, after centuries of neglect, The Revenger's Tragedy was put back on the map in the Swinging Sixties by a young director named Trevor Nunn. He scored his first big RSC success with a production that highlighted the manic mood-swings between macabre farce and lurid charnel-house poetry, and brought out the diseased phosphorescence of the glittering court. Comparisons were made with the way a later Italian society was savaged by Fellini in La Dolce Vita.

When Nunn re-established its theatrical vitality, the play was usually attributed (on meagre evidence) to Cyril Tourneur, author of The Atheist's Tragedy. The recently published Thomas Middleton: Collected Works, which gathers a vast and amazingly varied output, makes the case that it is unquestionably Middleton's. In this hefty, 2,000-page volume, the play sits alongside the author's works in all the dramatic genres, including the racy London city comedies whose wily scheming protagonists bear more than a distant family resemblance to Vindice, the hero of the The Revenger's Tragedy.

This week sees the opening of two new productions of the piece, both located in the present day. In the Olivier, as part of the National's Travelex £10 season, Melly Still directs a revival which stars Rory Kinnear. At the Royal Exchange in Manchester, Stephen Tompkinson takes the lead role in a staging by Jonathan Moore. Both directors are well up to speed with the conventions and preoccupations of revenge drama.

"It could equally be called The Revenger's Satire or The Revenger's Farce. It's a danse macabre and all of these things in one," says Moore, applauding "the demonic breakneck energy" that drives farce into "the dark recesses of the human soul". It's as though Middleton has taken Hamlet and "performed jazz riffs on it".

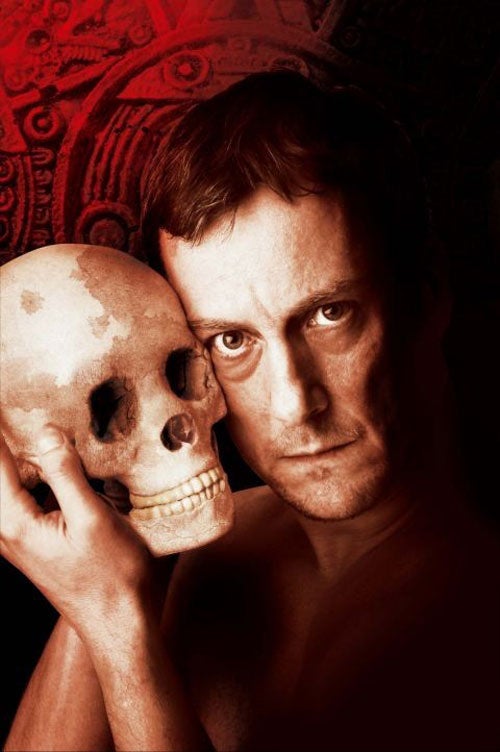

Shakespeare's tragedy is recalled in the opening image – the black-clad Vindice holding the skull of his beloved – except that here the hero has dug this object up himself as a spur to his long-postponed revenge, and it presides over the play as a stark memento mori. Middleton's hero is fixated by the skull's emblematic message: "Does the silkworm expend her yellow labours/ For thee? For thee does she undo herself?... Does every proud and self-affecting dame/ Camphor her face for this, and grieve her maker/ In sinful baths of milk?"

I wondered how the directors thought that Vindice would react to Damien Hirst's work For the Love of God – the skull encrusted with 8,601 flawless diamonds which went on the market at an asking price of £50m.

"I think he would be fascinated and repelled," says Moore, who reveals that he has put a photograph of this piece in the programme. Still agrees, perceptively arguing that "it's the kind of objet d'art that would attract Lussurioso" the Duke's decadent heir. "He'd have it in his study." Vindice, she reckons, would see right through it and satirise its pretensions to satire. For you could argue that in using real diamonds and in aiming for an astronomic profit, For the Love of God is an embodiment of the vanity of human wishes rather than the exposure of false values that it purports to be.

Both directors have thought hard about how to evoke the world to which Vindice returns – a hedonistic court in which the justice system has collapsed and where there's a frenetic pursuit of the "bewitching minute" of orgasm and murder. Still says that her production will show that there has been "a gradual pornographising of art". Vindice will be shocked to discover Lussurioso projecting actual pornographic images on to his Tintorettos and Titians.

In Moore's production, which will emphasise the power hierarchy, the hero is presented as a former barrister who is emerging from a long nervous breakdown caused by the killing of Gloriana and the victimisation of his family. The Duchess is a trophy second wife whose vile, idiot sons remind Moore of the suspects in the Stephen Lawrence trial. The play's last-minute twist demonstrates that "if you take on the Establishment, the whole apparatus of the state is going to come crashing down on you".

Both Still and Moore suspect that Antonio, the ostensibly virtuous nobleman who takes over is, in fact, a Machiavellian who is careful to keep his hands clean, while using the middle-class avengers to bring about bloody regime change by proxy.

Modern taste, though, requires psychological consistency in a hero. Is it possible to find this in Vindice, who alternately rails against the corruption of the world in stupendous poetry and takes a prankster's delight in devising ingenious torments? With actors of the calibre of Kinnear and Tompkinson, the new productions are hoping to prove that you can.

A particularly tough hurdle for director and performer comes when Vindice, disguised as a malcontent tough, is hired by Lussurioso to play the pander, and bribe his own family into prostitution. Why is he prepared to test his sister's and mother's virtue? For Melly Still, the key lies in his unresolved grief for Gloriana, festering for nearly decade. She must have been in a similar situation with another pander all those years ago. Mistrust stirs as shades of yesterday are summoned with a vengeance. It's as though, in the grotesquely ironic position of current tempter, he is conducting an agonised inquest on the past.

The warped humour of The Revenger's Tragedy often has a remarkably deadpan, modern ring. Gloatingly revealing his subterfuge to a dying victim, Vindice mocks him further with the whispered, hilariously superfluous advice to "tell nobody". That's the sort of gag that would have appealed to Orton. But, in digging deeper than ever for subtext, the new productions also look set to bring a rounded psychological reality to a play that is both striking in its own right, and Hamlet's antic, black-sheep cousin.

'The Revenger's Tragedy' is at the National's Olivier (020-7452 3000) to 7 August; and at the Manchester Royal Exchange (0161-833 9833) to 28 June

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies