Carlos Acosta, Sadler's Wells, London

In Acosta, we have a noble performer with nothing left to prove

When George Balanchine asserted that "ballet is woman", he was looking at a small window of time, at most 50 years. Before the early 19th century, men were the stars, and since the early 20th century, helped in no small degree by Balanchine's first muscular masterpieces Apollo and Prodigal Son, they've been powering their way back. No one who managed to land a ticket to Carlos Acosta's five-night showcase event can have been left in any doubt that the reinstatement of the manly in dance is now complete.

The curtain rises on a sight calculated to reduce Sadler's Wells's largely female audience to a puddle: Acosta, stripped to the waist, lying flat on the floor in a sunny, open-to-the-sky studio that looks to be by the Aegean. The piece is Jerome Robbins's Afternoon of a Faun, and it's both about male beauty and sensual absorption, and the inherent narcissism of ballet. As Debussy's languorous flute slithers into consciousness, the man stirs, lifts a leg, points a foot, and rotates it slowly. As the orchestral texture builds, the man rises to his feet and tries faunlike poses in front of an invisible mirror (the famous fourth wall which is of course us, the audience). This pointed scrutiny of an imagined reflection is a simple theatrical trick. Yet it never fails to trigger a private frisson as each spectator feels that they, and they alone, are being played to.

The seductive spell sustains even when Begona Cao arrives on the scene, as Acosta subtly registers her presence while continuing to regard himself. She, too, is interested mainly in admiring her lovely, leggy line as she runs through her practice pliés and stretches. Even when the pair come face to face, their eyes slide away to check how good they look together, and as the plucked harp notes bring the great heady swell of the music to a close, the man returns to his afternoon nap. Unlike Nijinky's onanist faun, who so offended Edwardian society with his horrid little judder over the maiden's dropped scarf, Robbins's is too in love with himself to bother.

Acosta has danced this brilliant piece of minimalism many times for the Royal Ballet, though not always with such sublime assurance. While in the past he has sometimes pointed up the comedy in the situation, now he coolly lets it speak for itself: the mark of a performer with nothing to prove. At 36, Acosta is probably at the peak of his dancing career, which is to say that, though his knees may be hurting and his jumps beginning to lose their height, his artistry makes up any deficit – no, more than makes it up. So it's not surprising to find him pursuing, or preparing to pursue, the career path of Mikhail Baryshnikov, an earlier virtuoso who refused to say die, and instead set about finding new choreography to suit a mature artist.

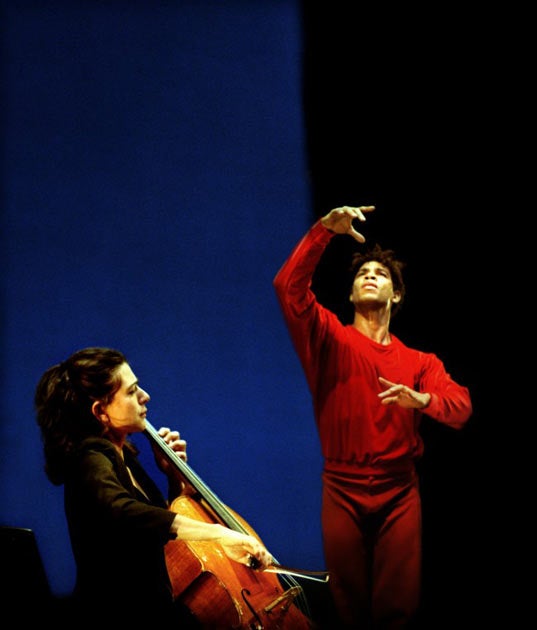

Step up, once again, Jerome Robbins, whose Suite of Dances – a duet for a man and a cello (here the excellent Natalie Clein, playing solo Bach in the romantic spirit of Brahms) – gently pokes fun at the performer who feels happier going at a jog than a sprint. As the on-stage cellist romps through fast arpeggios, the dancer repeatedly flags, only to be spurred – or shamed – by the music into more energetic action. It's a neat device, not least because in the end, after much mugging and pouting and pretend exhaustion, the dancer pulls off some stunning fast travelling pirouettes and a few big jumps. My major gripe was with Acosta's mismatched red top'n'slacks combo, which left him looking like a badly painted postbox.

By contrast, the white one-shouldered Lycra job that is required wear for Apollo – and which makes so many otherwise great physical specimens look pasty – is glorious on Acosta. With his muscled golden form set against Balanchine's signature Athens sky, he's the closest to a Greek god we're ever likely to get. But it's the dignity inherent in the title role that makes this 1928 modernist classic ideal Acosta territory. In the old days, he would have been called a danseur noble: he has more of that quality than any other man dancing today.

Yet he combines that nobility with an imaginative engagement with the role that lights up its more obscure corners: handling Apollo's lyre with the bragadoccio of a rock star with his first Stratocaster; lining up his three Muses like a cat that got the cream (can things get any better for a junior god?), and testing the tension in their triple-linked arms with an avidness that made me – dozens of Apollos under my belt – see their symbolism: the interdependence of all art.

The evening is completed by Young Apollo, a new work by Adam Hougland set to a zingy score by Britten. Danced ably by Erina Takahashi and Junor de Oliveira Souza (allowing Acosta a breather), it makes a small, if nicely contrasting impact. The mighty Apollo has no match.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies