Here We Go, National Theatre, review: This is unforgettable

You feel as though you've aged a decade as the light gradually fades

“Most things may never happen: this one will”. Philip Larkin imbued with a matter-of-fact ruefulness the idea that since death is inevitable, it's uniquely reliable in his poem “Aubade”. The gallows humour is more teasing and laconically linked to the inherent poignancy of the material in Here We Go. Immaculately directed by Dominic Cooke, this is a 45-minute triptych in which Caryl Churchill, now 77, muses on the subject of what Larkin in a different poem calls “the only end of age”. The piece plays typically serio-comic and challenging games with form, and it sends you back into the outside world valuably disoriented as to how human beings negotiate experiences penultimate, ultimate and conjecturally beyond.

The three parts are performed by a crack cast in a purposefully out-of-sequence arrangement. We begin with the polite chit-chat of a group of mourners at a well-heeled wake. We overhear eight unnamed characters of widely different vintages exchange splintered, cut-off remarks about the deceased – evidently a man of the Left, a looker (“a vision at thirty”), an MP in the 1950s and indiscriminately bad-tempered. There's a jagged, absurdist music to their scatter-shot recognition of loss– “it comes at you suddenly doesn't it/like stepping on a rake – that is counterpointed by the non-naturalist asides where each of them straightforwardly announces to the audience the time and circumstances of their own death: “I die twenty-three years later after nine years of Alzheimer's. I don't know anyone who's there”.

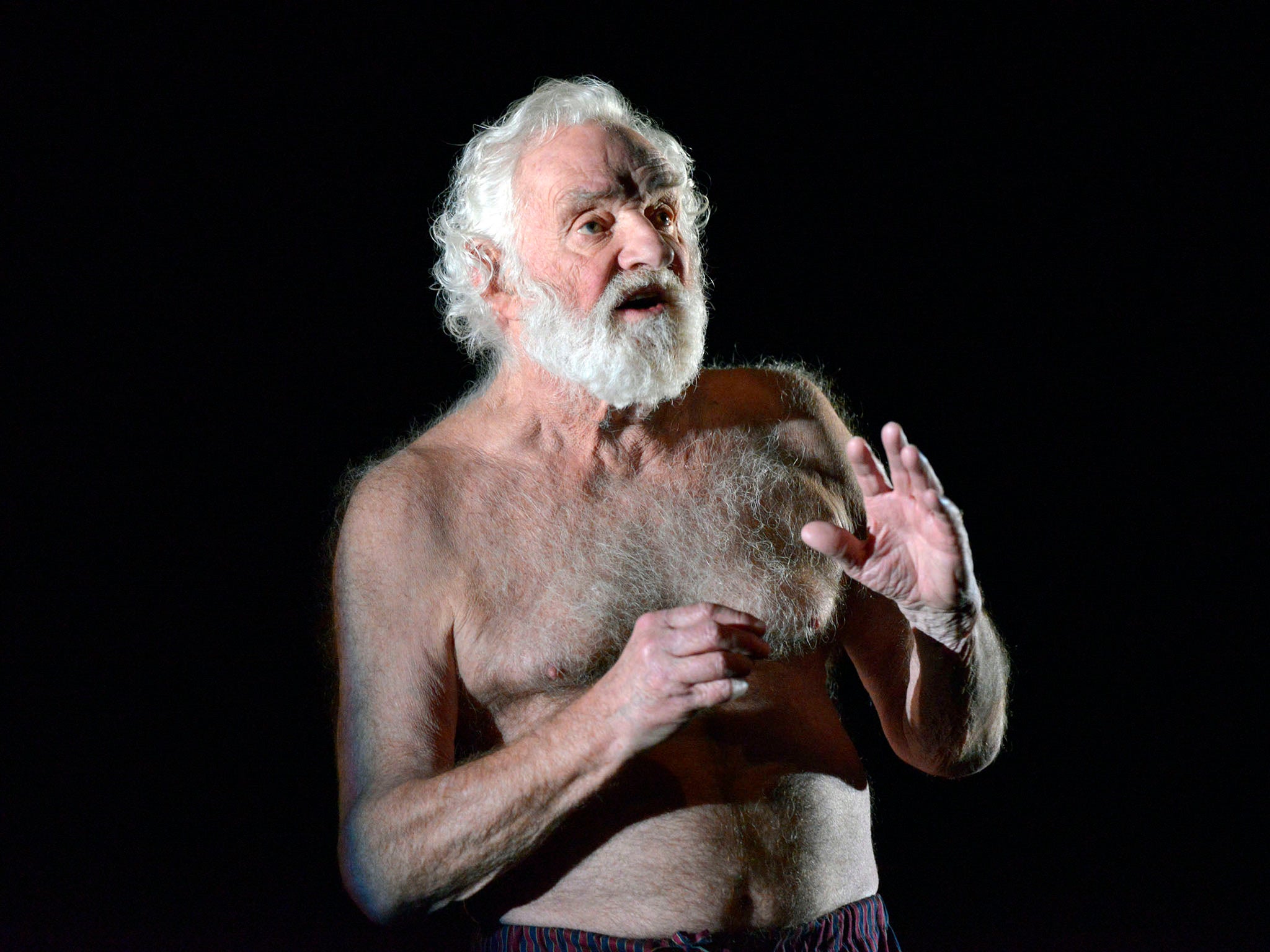

The white abstract setting by Vicki Mortimer is alarmingly engulfed in blackness. Then we see the biblically silver-bearded, bare-torsoed Patrick Godfrey (presumably the dear, departed) floating, as though a figure in some collaboration between Beckett and Dante, in a terminal tunnel sculpted by Guy Hoare's superb lighting design. There's dark intellectual farce her as our driven, flustered protagonist wonders into which system of reward, retribution, or reincarnation a free-thinking unbeliever like himself may have blundered. What hell could it possibly be when the whole idea of an individual deserving of hell has been questioned by one kind of liberal thinking (“what would it be like to have to live your life a someone obsessed with having sex with children?”). Or when the medieval hell of “tortures pincers and fire” is so manifestly an ongoing heaven-on-earth for certain sadists and terror regimes?

The impact of the piece is heightened rather than dissipated by the large, wide scale of the Lyttelton. This is confirmed, I think, by the concentrated effect of having so many people forced to bear what becomes mountingly unbearable witness in the final sequence. Here Churchill offers a vision of a living purgatory as Patrick Godfrey (excellent in both sections) in the role of very old, sick person and his female carer perform a Sisyphean routine of getting dressed, undressed, and undressed on a loop that is not lacking in professional solicitude and would certainly be better than dying alone in a ditch but which I devoid of that touch of personal affection that might put a flicker of fortitude into his passively suffering face. You feel as though you've aged a decade as the light gradually fades on a quietly remorseless quarter an hour of this. Like the whole of Here We Go, unforgettable.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments