I Don't Believe in Outer Space, Sadler's Wells, London

The tone for William Forsythe's I Don't Believe in Outer Space is set by dancer Dana Caspersen, who acts out both sides of a conversation with such exaggerated physical and vocal mannerisms that she becomes a postmodernist Gollum act.

Caspersen plays both a creepy new neighbour and the perky housewife he drops in to visit. Between lines of dialogue, she performs and describes the characters' body language – "head tilt to the side, eyes to the ceiling". She also puts on caricatured voices: a helium squeak for the housewife, a hoarse growl for the neighbour. It's a frantically arch performance.

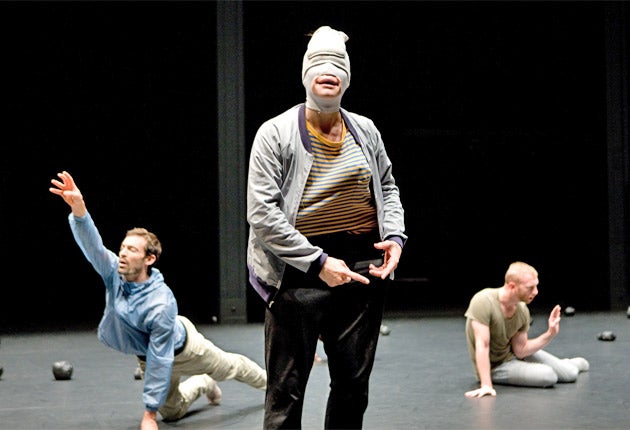

I Don't Believe in Outer Space is Forsythe at his most self-consciously theoretical. The bare stage is draped in black. One side is closed off; on the other, you can just see brightly coloured pictures and objects piled up in the wings. The music, by Thom Willems, cuts from humming soundscapes to blasts of jazzy lounge music – distracting, apparently random sound.

Little parcels of gaffer tape litter the floor. Dancers throw them, ignore them, tuck them into their costumes. There are several character scenes, mostly played by Caspersen. The dialogue slides into song lyrics: sooner or later, everyone ends up speaking the words to "I Will Survive". In one sequence, a dancer appears to be speaking – until she stops, and the voice carries on, with other dancers lip-synching the words in turn.

The dancing happens around the edges. Forsythe's company can wriggle into astonishing isolations, bits of the body moving against itself. Gathered together, they all dance in different rhythms, everyone in his or her own little world.

They turn steps inside out with silky fluidity. When Forsythe experiments with movement, he can break it up and pull it in new directions without losing its clarity or momentum. His fragmented speeches just don't have that weight. In one scene, a male dancer, his face muffled in a woolly hat, plays a researcher who discusses the futility of research. It's slight, but it's more effective than Caspersen's antics: he doesn't work so hard to be artificial.

Caspersen, a long-term Forsythe collaborator, is a remarkable performer. In one sequence, she croons and screeches, moving as if her legs are broken, bits of her body twitching in isolation. The layers of artificiality are deliberately put on. Her performance is probably the best expression of Forsythe's style in this piece. It's also the one I find hardest to take: the most calculating, the most mannered. Caricature can give a performance more energy, underline points, add bite. In this case, the exaggerations are there for their own sake, ham in a vacuum.

When Forsythe and Caspersen show the meeting of creepy neighbour and perky housewife, it's a moment of social embarrassment, but it's not an embarrassment that anyone involved seems to feel. These aren't exactly characters; they're a starting point for a theatrical game, constructs who give Caspersen material to play with. It's a joke that half this audience happily responded to, while the others sat silent.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments