Rambert mixed bill, Sadler's Wells, London<br/>Royal Ballet double bill, Royal Opera House, London

A contemporary British classic raises some laughs, while an American ballet from the Seventies brings out the hankies

It's been a good week for buried treasure. Britain's two most venerable dance companies – Rambert and the Royal Ballet – have both exhumed hits from the past, and though neither had to dig very deep to find them, both items feel as if their time has come again. Both, too, depend for their success on a major dose of charm – a fragile thing. Yet both revivals show their respective companies at their freshest.

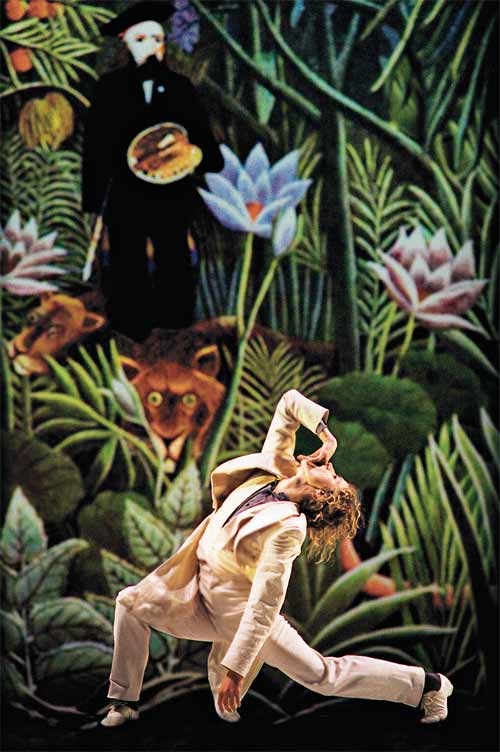

For Rambert, the find was a piece of vintage Siobhan Davies. Made in 1982, her Carnival of the Animals, set to Saint-Saëns, has all the spare, cool obliqueness of early British contemporary dance with an added touch of Johnny Morris. Against a richly lit reproduction of "Le Douanier" Rousseau's self-portrait with jungle animals, dancers in natty white tailoring respond to the music's imagery in the least obvious of ways.

The Hens & Roosters squeak their sneakers against the floor in a fussy disco strut, a pair of can-can dancing Tortoises crouch under giant feathered fans, while the Cuckoo's clarinet call becomes the beating heart of an unrequited lover, a Buster Keaton in blazer and boater and sweet, lugubrious face. The pogo-jumping piano hammers clearly drew a blank for some of the audience. This was the composer's little in-joke, "Pianists" being zoological specimens in his view.

Just as inspired, though superficially more conventional, is Davies' male solo Swan. Almost simultaneously we're made aware of not just the creature's elegant stretch and power, but also the eddying surfaces around it, even its bulky contact with the water. It's a small miracle of distilled and cross-connected imagery – the sort of thing lit-crit would have a long Greek word for.

The ultimate highlight, though, both musically and visually, is the glistening Aquarium sequence, as the full complement of Rambert dancers don long, blue satin gloves for a Hollywoodesque display of synchronised swimming. Hats off to conductor Paul Hoskins for the glistening, glamorous veil of orchestral colour he drew from the London Musici in the pit. Pure magic, and worth the ticket in itself.

The brand new item on this bill is a work by Doug Varone who sets off the most unsettling train of thoughts by revealing, in a programme note, that Scribblings was inspired by "the ballet of cockroaches scuttling to hide" every time he turned the light on in his student New York digs. It's set to John Adams's Chamber Symphony, which itself sounds like an axe-attack on a piano factory – thrilling, actually, in the way its crashing clamour goes relentlessly on: you keep thinking it's about to reach a climax and pause for breath, but it doesn't, it only gets louder, and when it does eventually stop it just cuts out, mid-clang.

Happily I'm not that familiar with cockroach habits. Suffice to say that Scribblings is full of furious running in circles, scratchy wriggly leaps and what looks suspiciously like beetle mating strategies. It's fast, fun, and doesn't outrun its material. Too bad that, in the performance I saw, the giant rise-and-fall lampshade got stuck low over the stage, and though orchestra and dancers went gamely on (only the dancers' legs comically visible under its rim), artistic director Mark Baldwin strode on stage and called a halt. "Didn't you notice anything wrong?" he threw at the hapless conductor. No doubt he did, but professionalism drove him on. He deserved his extra cheers at the end.

But back to archaeology. Over at Covent Garden, the Royal Ballet marked the 10th anniversary of the death of Jerome Robbins with a piece it hadn't danced for 32 years. Back in the Seventies, Dances at a Gathering broke significant new ground. While audiences had got more or less used to new ballets not being about anything specific, it was a novelty to find one in a romantic vein where couples swapped about. Indeed, one or two of its cast of 10 didn't appear to belong to anyone. Some set up in competition with one another. Others just walked about, as friends often do. But this isn't a display of free love so much as fragments of interlocking lives. Set to a non-stop sequence of Chopin piano waltzes, mazurkas and polonaises (another first: no orchestra!), Dances' rehearsed casualness mirrors the music's feeling of improvisation. At the opening, a lone male (on Wednesday, Carlos Acosta) wanders on, seems to remember something, wanders some more, then gradually forms his thoughts into spacious, ravishing dance.

Dances goes on in this vein, spinning sequences of dazzling innovation with an almost throwaway air. Space is a constant feature. Against a clear blue sky, dancers have room to run and leap and fly and gaze into vast distances. The result: an hour-long hush such as I've rarely known in a theatre. Put it down to Chopin (and Philip Gammon who draws magic from the keyboard); put it down to Robbins' genius for imbuing steps with an inner life. But this seasoned watcher kept having to blink back tears.

'Dances': ROH (020 304 4000) to 10 June

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies